Fighting for Sanity: John Ruskin (1819–1900). After recovering from a psychotic break, English critic John Ruskin was determined to remain stable and continue to work. He tracked his health in his diary.

Fighting for Sanity: John Ruskin (1819–1900). After recovering from a psychotic break, English critic John Ruskin was determined to remain stable and continue to work. He tracked his health in his diary.

About the Diary

Fifty-seven-year-old John Ruskin, the great English critic, started a new diary in 1876. He wrote in a tall, narrow volume—just over a foot high and six inches wide—with printed page numbers on the ruled leaves and the word "ledger" stamped on the spine. As the year began, he was characteristically busy juggling a multitude of projects, from scholarly pursuits to social initiatives, such as classifying minerals for a new museum to serve the local working class. For nearly seven years he turned to this diary almost daily whenever he was at Brantwood, his home in the Lake District of England, sometimes using a different volume to keep track of his days when he was away teaching or traveling.

Ruskin found himself "crushed under business," often languid and depressed, but open to the beauty of nature—from an "exquisite broad rainbow" to a bright sunset or a new moon that shone like limelight. With the local ironworks spewing waste into the air around his home, Ruskin felt oppressed by the industrial darkness: "Black — black — black — soot and rain mixed—and my own mind in some ways like it."

By early 1878, Ruskin was in a fragile state, feeling "cold and dead," losing interest in those aspects of life that once gave him joy. Even the diary seemed a fruitless exercise as he watched "how the useless mass accumulates." He confessed to feeling a "perpetual fog and depression of my total me—body and soul,—not in any great sadness, but in a mean, small, withered way." In late February, Ruskin collapsed. For over a month he lay prostrate, tormented by psychotic nightmares, paralyzed by a sense of his own worthlessness. His diary lay untouched. When he emerged from his room in early April, he picked up the volume and made a simple entry on two pages left otherwise blank: "February to April—the Dream." He was ready to reenter life.

By early 1878, Ruskin was in a fragile state, feeling "cold and dead," losing interest in those aspects of life that once gave him joy. Even the diary seemed a fruitless exercise as he watched "how the useless mass accumulates." He confessed to feeling a "perpetual fog and depression of my total me—body and soul,—not in any great sadness, but in a mean, small, withered way." In late February, Ruskin collapsed. For over a month he lay prostrate, tormented by psychotic nightmares, paralyzed by a sense of his own worthlessness. His diary lay untouched. When he emerged from his room in early April, he picked up the volume and made a simple entry on two pages left otherwise blank: "February to April—the Dream." He was ready to reenter life.

For the rest of year he made only a few brief notes in the diary, but resumed his practice of daily jottings in January 1879. As the anniversary of his mental collapse approached, he was wary but grateful. He watched a fresh white snow melt to "grey waste" and cautioned himself, "Let me see that I don't thaw away into waste myself, now the Spring's come again for me, once more!" By March he felt "depressed enough, but knowing my battle now better than when it beat me last year." When he marked the second anniversary of his reemergence in 1880, he embraced the coming spring: "Two years since I began to wake from the long dream. Primroses and violets just in sweet beginnings, and periwinkles beaming in my ivy bank, made me happy yesterday."

As the years passed, Ruskin suffered several additional breakdowns, though none as dramatic as the 1878 nightmare. After one episode in 1881, he wrote to a friend, "I CAN'T understand how so extremely rational a person as I am can lose their wits, and still more, how they don't know they have lost them at the time. I do think if I were to go crazy again for the third time I should know I was so." His was determined to study his own patterns and learn enough about himself to remain sane, and he used the diary as a tool to that end.

He reread his earlier entries, searching for signs leading up to his breakdown, underlining key words and phrases, compiling an index of his experience, and putting down on paper all he could remember of his psychotic visions. When he had filled all the right-hand pages of the diary, he went back to the beginning of the book and began filling the left-hand pages, so that his new entries appeared opposite entries from past years, forcing him to confront—and comment on—his younger self. In his final entry, written on January 1, 1884, Ruskin greeted the new year with optimism: "Tuesday. Very thankful to be spared to see the light, and begin the labour, not unhopefully, of this New Year."

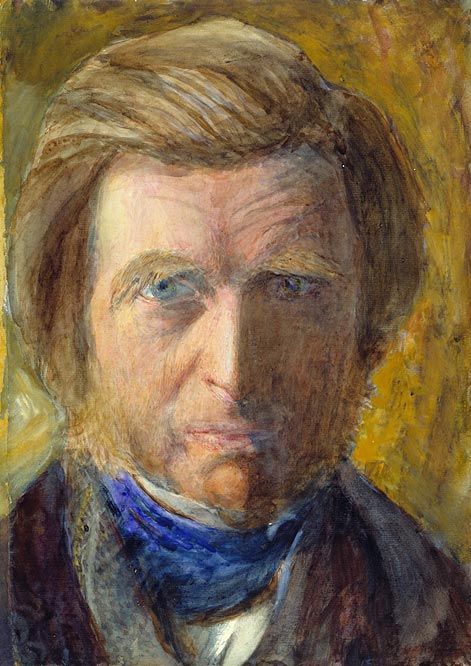

John Ruskin (1819–1900), Self-Portrait, in Blue Neckcloth, Watercolor and gouache, Gift of the Fellows; 1959.23

Diary entry made by John Ruskin (1819–1900) after his 1878 breakdown. Bequest of Helen Gill Viljoen, 1974.