Collections Spotlight

Objects on view in J. Pierpont Morgan’s library reflect the past, present, and future of building collections in four curatorial departments, comprising illuminated manuscripts from the medieval and Renaissance eras, five hundred years of printed books, correspondence and literary manuscripts, as well as printed music and autograph manuscripts by composers. These selections, which rotate twice a year, provide an opportunity for Morgan curators to spotlight individual items in different ways—to consider their historical and aesthetic contexts, artistic techniques, and some of the stories behind these artifacts and their creators.

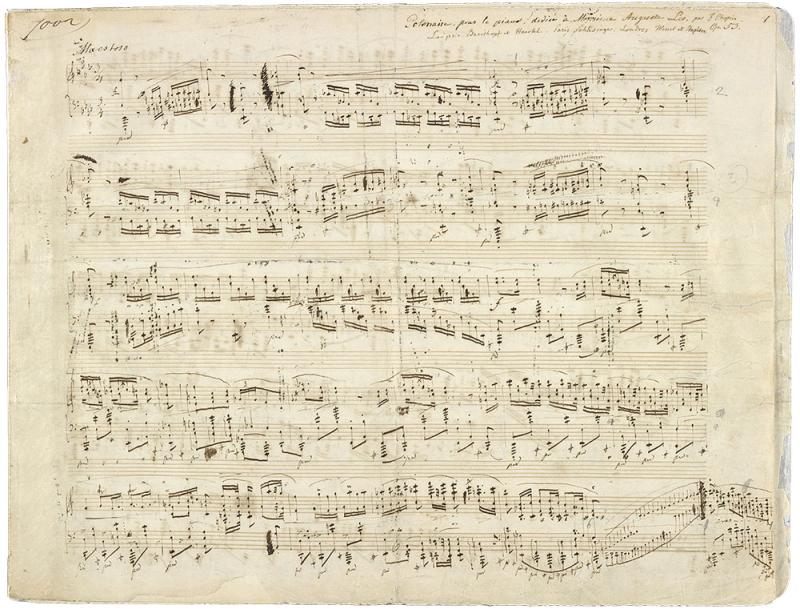

Frédéric Chopin, 1810–1849. Polonaise for piano, op. 53, in A♭ major : autograph manuscript, ca. 1842, Heineman MS 42

A New Friendship, a New Sonata

The current installation features a music curator’s recent rediscovery in our holdings of a portrait of George Bridgetower (ca. 1778–1860). A violinist of African and European descent, Bridgetower was the recipient of a dashed-off note in Beethoven’s hand, also on view. This brief missive, comparable to a modern-day text message, evokes the warmth and intimacy of the friendship forged by the young musicians. That sentiment also infused the composition Beethoven wrote for Bridgetower, a sonata for violin and piano designed to showcase his extraordinary skills. In his dedication, Beethoven called the composition “sonata mulattica,” a reference both to the violinist’s biracial status and to the music’s unusual blend of major and minor, sonata and concerto. Beethoven rededicated the piece, however, to a French violinist whom he barely knew: Rodolphe Kreutzer, who never even played what is now called the “Kreutzer” sonata.

Summers in the Country

An autograph manuscript by Chopin, once owned by the pianist and composer Clara Schumann (1819–1896), is also on view. Polonaise for piano, op. 53, in A-flat major was likely written in 1842 in the French village of Nohant, where Chopin spent summers with his partner Amantine Dupin (1804-1876), the French novelist known by her pen name George Sand. These breaks from city life provided a stable environment to work and allowed Chopin to create some of his best- known music. This boldly patriotic piece is based on a dance from his native Poland. It has since become a core part of the piano repertoire. In addition to Chopin’s famous polonaise, visitors can see music manuscripts by Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky (1839–1881), Richard Strauss (1864–1949), and a collection printed in 1800 of dirges, hymns, and anthems, commemorative of the death of “the Guardian of his Country, and the Friend of Man,” George Washington.

Francis Barlow (ca. 1626–1704), illustration from Aesop’s Fables with His Life, in English, French & Latin, London: printed by William Godbid for Francis Barlow, 1666. Purchased as the gift of Mrs. Alexander O. Vietor in memory of her daughter, Barbara Foster Vietor (1956–1966), 1994. PML 127666

Countee Cullen (1903–1946), Color, New York and London: Harper & Brothers, 1925. The Carter Burden Collection of American Literature. PML 184727

A Lion in Need Needs a Mouse Indeed

Aesop (ca. 620–564 BCE) remains the most popular fabulist in Western civilization. Several of his fables center on a mouse aiding a lion, with the timeless moral that even the mighty need help from the small. The artist Francis Barlow (ca. 1626–1704), who created the extraordinary edition on view, was one of the most prolific illustrators of wildlife and sporting scenes in seventeenth- century England. For the book, published at his own expense, Barlow created 112 engraved illustrations. The text is trilingual: a short summary of each fable in English precedes the full stories in Latin and French. Barlow hoped this format would help readers learn foreign languages. Fewer than twenty copies of this edition survive, as most were destroyed in the Great Fire of London, which swept through the printer’s shop in 1666.

A Poet-Prodigy’s First Book

Countee Cullen (1903–1946) began writing verse at age fourteen. By the time he attended New York University, his poems were being published in magazines associated with the Harlem Renaissance, such as The Crisis and Opportunity. His first book Color was published during his senior year. Cullen’s career was sometimes viewed as controversial. As a poet, he pointed to John Keats as a model; as a critic, he once faulted Langston Hughes for the use of Black vernacular. Color, however, draws on the language and subject matter of Black culture and reflects Cullen’s preoccupation at the time with social justice. He inscribed this copy to Faburn DeFrantz (1885–1964), a galvanizing force in Black activism in Indianapolis, who organized famous readings and concerts, including one that featured Cullen in 1927. Additional printed items on display include works by the early modern poet Katherine Phillips (1631/2–1664), known in her coterie as “the matchless Orinda”; Maurice Gonon’s edition of Saint-Exupéry’s Vol de nuit, with illustrations by Camille Paul Josso and a designer binding by Georges Poget; and a copy of the horrific diagram of the slave ship Brookes, commissioned by the British abolitionist Thomas Clarkson (1760-1846).

Maria Hadfield Cosway (1760–1838), watercolor on paper, in Letter to Mrs. Dalton, [after 1791]. Gift of Mina R. Bryan in honor of the fiftieth anniversary of the Library, 1974. MA 2849

Langston Hughes, 1902–1967, The strollin' twenties : typescript, 1965 Nov. 26, Gift; Family of Carter Burden, MA 5491.

A 1960s Take on the Harlem Renaissance

The Morgan’s copy of the typescript for Langston Hughes’s 1966 musical television special, The Strollin’ Twenties, is signed by a panoply of major Black cultural figures of the twentieth century. In addition to Hughes’s own signature, the title page is inscribed by two of the production’s actors, Sidney Poitier (b. 1927) and Diahann Carroll (1935–2019), and composer Duke Ellington (1899–1974). Another signature visible on the page belonged to the teleplay’s producer: singer, actor, and activist, Harry Belafonte (b. 1927). Belafonte was inspired to instigate the project after reading Hughes’s autobiographical account of his early years in New York—an era Belafonte rightly called “one of the most rewarding and culturally fulfilling times in our history.”

A Hidden Miniature

The illustrated letter on display, addressed to a “Mrs. Dalton,” is written in the hand of Maria Hadfield Cosway (1760–1838) —a celebrated painter and a pioneer of girls’ education in Italy. Cosway used the square created by the folds of the letter to draw a thumbnail of her painting, now lost, titled Eros the Love Creator Dividing Chaos. Of this work of art, she wrote, “I cannot say much on my own picture but that I am very fond of the subject.” Other authors represented in this section of the East Room include Grace Paley (1922–2007), William Wordsworth (an early draft for “The Monument Commonly Called Long Meg and Her Daughters, Near the River Eden”); and Mary Antin (1881–1949), a tireless advocate for open immigration policies, whose letter describes her anticipation of attending the dedication of a monument to Booker T. Washington (1856–1915) in 1922.

Gospel Book (“Matilda Gospels”), in Latin, Italy, San Benedetto da Polirone, end of the eleventh century. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1912. MS M.492, fols. 59v–60r

Badr al-Dīn Hilālī (d. 1532/33), Shāh va gada, Bukhoro, Uzbekistan, 1540. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) before 1913. MS M.531 fol. 13r

Pierpont Morgan’s Finest Italian Romanesque Manuscript

On view from the department of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts is a Gospel Book commissioned by Countess Matilda of Tuscany (1046–1115) as a gift to the Abbey of San Benedetto di Polirone, founded by her grandfather in 1007 near Mantua. In addition to decorated canon tables, initials, and evangelist portraits, there is an elaborate series of twenty-seven illustrations from the life of Christ—an uncommon subject in Italian manuscripts at this time. Scenes, which include depictions of the Circumcision of Christ, the Presentation in the Temple, and Christ Among the Doctors, were drawn and gilded but never painted. Whether unfinished or intentionally left unpainted, the quality of these drawings places them among the masterpieces of Italian Romanesque art.

Persian Poetry

Widely praised for its eloquence and originality, poetry by Badr al-Dīn Hilālī is considered to be among the most refined examples of Persian literature in the sixteenth century. Ultimately, the poet’s way with words may have been his downfall: he was publicly executed in 1532/33, presumably for offending the Uzbek ruler ‘Ubaid-Allāh Khān. The manuscript on display is an early copy of Hilālī’s mystical poem about a lowly beggar who becomes enamored with a handsome prince. It was inscribed by one of the most outstanding calligraphers of the time, Mir ‘Ali al-Katib al-Sultani, and illuminated by an unknown artist likely working in Bukhara. Other treasures on view include a fifteenth-century example of Spanish illumination; a twelfth-century cycle of paintings on the life of Christ, created in Northern France; and a Book of Hours illuminated by Noël Bellemare, which beautifully blends French Renaissance motifs with a Flemish Mannerist style.

Collections Spotlight is funded in perpetuity in memory of Christopher Lightfoot Walker.