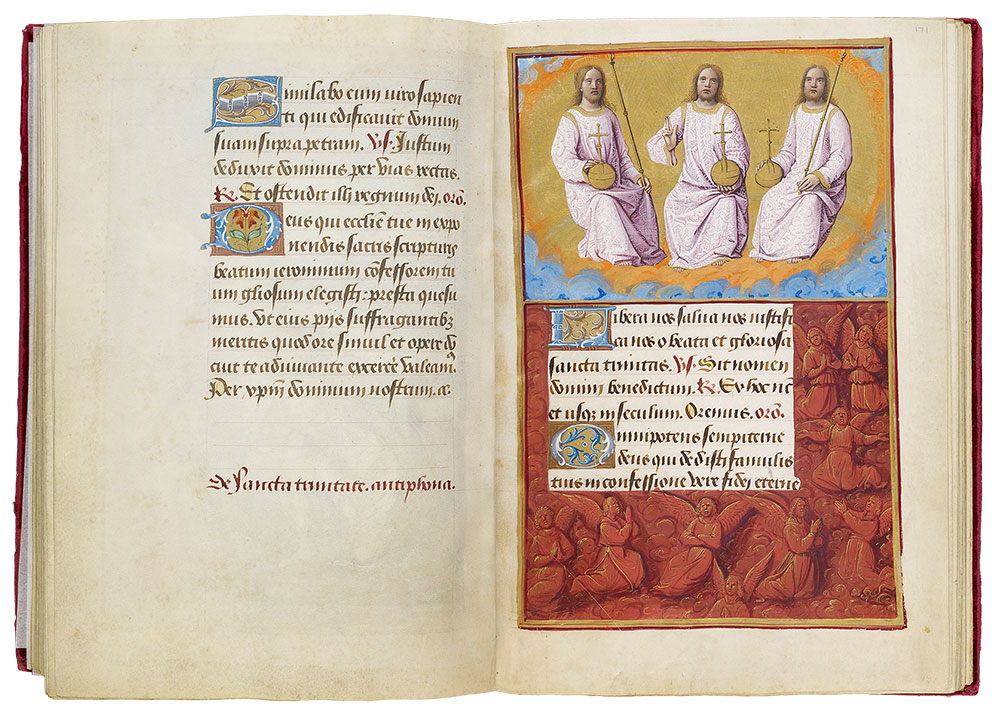

Suffrages, fol. 170v

Trinity: Trinity

Hours of Henry VIII

Illuminated by Jean Poyer

Gift of the Heineman Foundation, 1977

Trinity: Trinity

Border: Angels (fol. 171)

The Christian conception of a triune God, each part equal and indistinguishable, is the subject of this miniature. (The same corruption can be seen in Poyer's Prayer Book of Anne de Bretagne, M.50, fol. 1.)

The Three Persons of God, seated on a golden rainbow within an aureole surrounded by clouds, are physically and hierarchically identical: they each appear as a young Christ holding an orb. It is tempting to identify the central blessing figure as God the Father, flanked by Christ at his right hand (as in the Apostles' and Nicene Creeds) and the Holy Spirit at his left.

Three Persons of God

The Athanasian Creed (sometimes called the "Quicunque vult" from its opening words in Latin), which specifically emphasizes the equality of the Three Persons of the Trinity, is included as the last text in the Hours of Henry VIII (fols. 196–99v).

Trinity Sunday, the feast day dedicated to the Trinity, was not originally celebrated in the early Christian Church. Although it was observed regionally in the tenth century, it was not universally accepted until 1334, when Pope John XXII (r. 1316–34) ordered it to be generally observed. (Feast day: the first Sunday after Pentecost, or the eighth Sunday after Easter)

Nine Orders of Angels

The nine celestial angels kneeling in adoration and prayer below may recall nine orders of angels, a hierarchy codified in the fifth century.

The ranks of the nine orders of angels were codified in the fifth century in De Hierarchia Celesti, a work that was attributed to Kionysius the Areopagite, the convert St. Paul. The choirs were grouped hierarchically:

- Seraphim, Cherubim, Theones

- Dominations, Virtues, Powers

- Princedoms, Archangels, Angels

The first group perpetually adored God, while the second group made the stars and elements. The princedoms protected earthly kingdoms, and the last two were messengers.

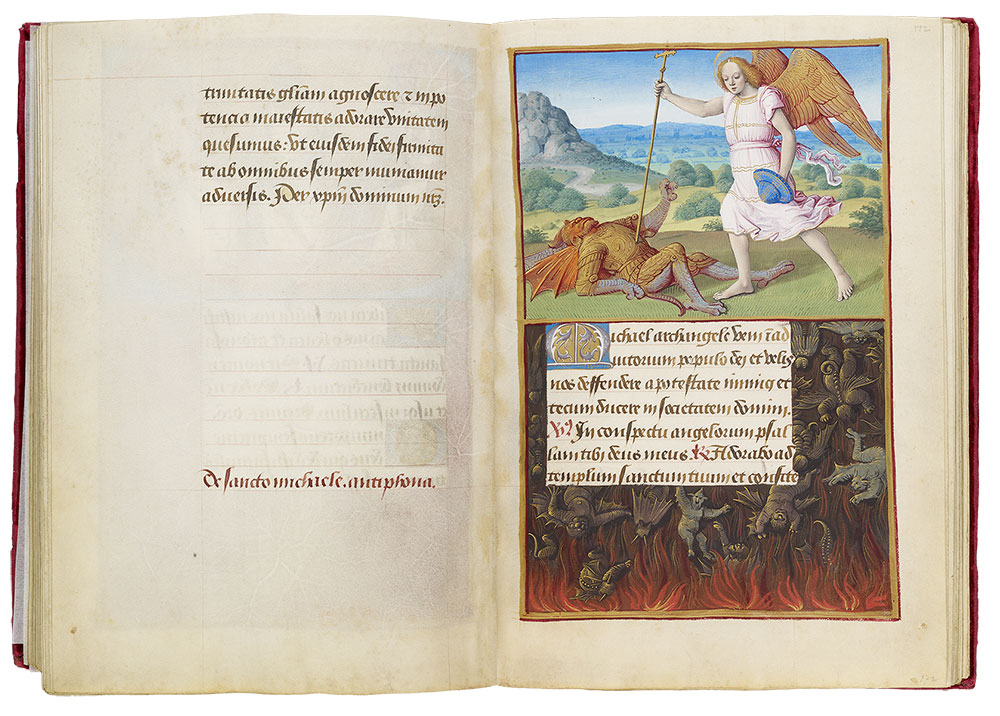

MS H.8, fols. 171v–172r

St. Michael the Archangel: Michael Battling a Devil

Hours of Henry VIII

Illuminated by Jean Poyer

Gift of the Heineman Foundation, 1977

St. Michael the Archangel: Michael Battling a Devil

Border: Fall of the Rebel Angels (fol. 172)

Throughout the Middle Ages, St. Michael's iconography varied. We know him best in armor or at least minimally carrying a shield (as here) while slaying the Devil in the form of a dragon or demon.

With a cross-surmounted spear Michael stabs the defeated Satan, who is garbed in antique- style armor (a convention Poyer acquired while visiting Italy).

Michael is sometimes confused with St. George, who also slew a dragon, but there is an easy way to distinguish the two. George, a canonized human, is never depicted with wings, while Michael, an archangel, always has them. (Feast day: September 29, Michaelmas)

In the margin, Satan's corps of rebellious angels, changed into demons, fall into the flames of hell.

St. Michael the Archangel

St. Michael the Archangel is God's commander in chief in the war against the Devil. In his dramatic confrontation with Satan at the beginning of time, Michael defeated his army and hurled the fallen angel and his minions into hell. At the end of the world it is said that Michael will return to earth for his final battle with the Antichrist. The archangel's second duty will be to weigh the souls of the departed and determine if they can enter heaven.

Michael's cult began in the East, where he was invoked for care of the sick (Constantine built a church near Constantinople for this purpose). A fifth-century apparition on Monte Gargano (in southeast Italy) was important in spreading the cult to the West. In the later Middle Ages, the Valois dynasty of French kings adopted him as their patron saint.

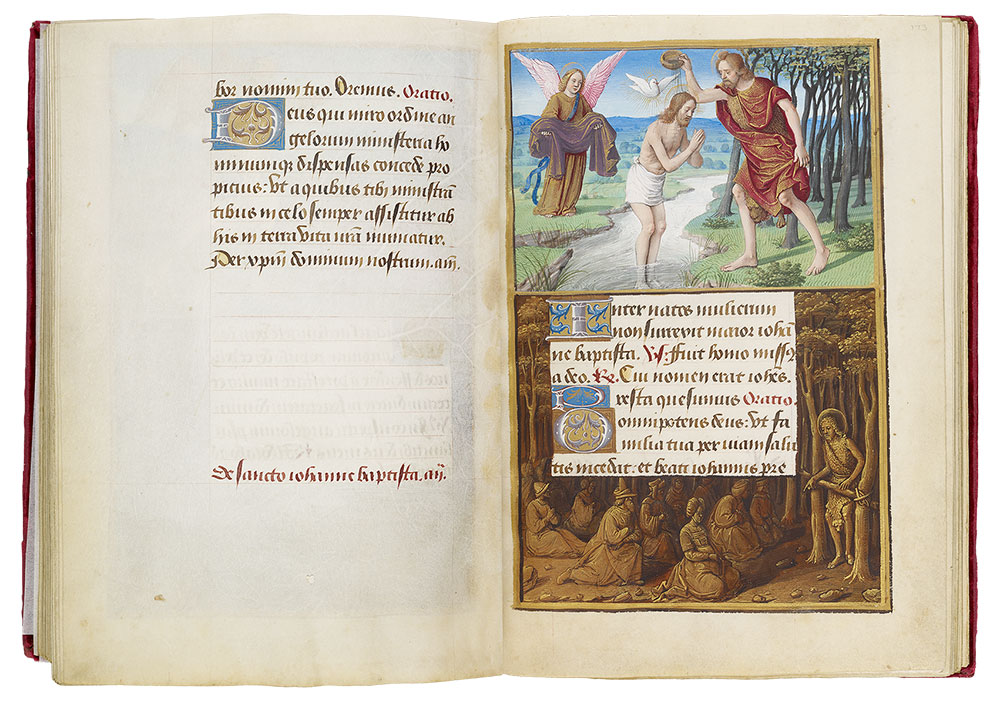

MS H.8, fols. 172v–173r

St. John the Baptist: Baptism of Christ

Hours of Henry VIII

Illuminated by Jean Poyer

Gift of the Heineman Foundation, 1977

St. John the Baptist: Baptism of Christ

Border: John the Baptist Preaching (fol. 173)

Around A.D. 27, St. John the Baptist moved to the desert of Judea near the river Jordan, where he preached penance, the coming kingdom of God, and baptism for the remission of sins; he lived on locusts and wild honey and wore a camel's hair garment.

While St. John is normally depicted wearing a leather girdle and a garment made from camel's hair, Poyer clothed him in a camel skin instead, with the camel's head and even a paw bumping about the saint's knees. John's long hair and scruffy beard identify him as a hermit.

St. John baptized Jesus in the river, recognizing him as the Redeemer when the Holy Spirit descended above him in the form of a dove. In the miniature, an angel waits on the opposite bank with Christ's robe.

In the margin, John preaches to the multitude in a forest, his pulpit formed by a branch hori- zontally attached to two tree trunks. (Feast day: June 24)

St. John the Baptist

The Archangel Gabriel told John's elderly parents, Zacharias, a Jewish priest, and Elizabeth, the Virgin Mary's cousin, that they would have a son named John. After Gabriel informed Mary that she, too, would have a son, the two women visited each other (the Visitation); on that occasion John leaped in his mother's womb at the presence of the yet unborn Jesus. Although the Golden Legend says they were childhood playmates, John and Jesus did not meet again until manhood.

St. John's outspoken preaching led to his martyrdom. He publicly censured Governor Herod Antipas for his incestuous marriage with his brother's wife and was subsequently imprisoned in the fortress of Machaerus. The dancer Salome, who had attracted Herod's notice through her dancing at his birthday feast, demanded and received the Baptist's head on a platter.

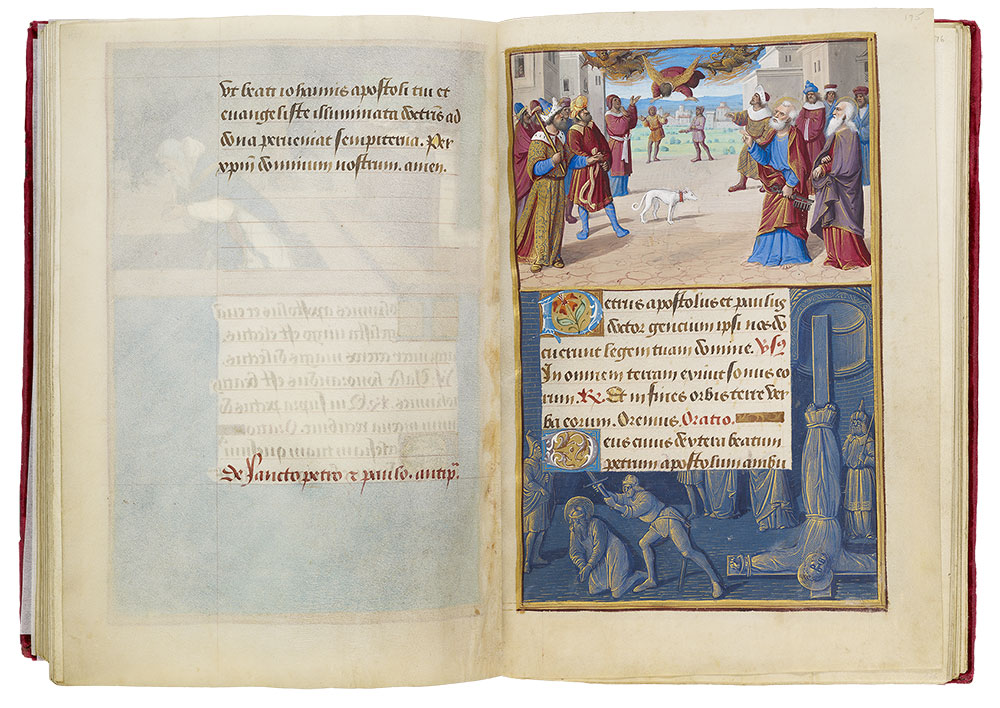

MS H.8, fols. 173v–174r

St. John the Evangelist: John the Evangelist Descending into His Grave

Hours of Henry VIII

Illuminated by Jean Poyer

Gift of the Heineman Foundation, 1977

St. John the Evangelist: John the Evangelist Descending into His Grave

Border: John and the Beast of the Apocalypse (fol. 174)

St. John was a prominent figure in the early Church. He preached in Samaria and Jerusalem with St. Peter and traveled on to Rome, from where he was presumably exiled to Patmos under the persecution of Emperor Domitian. Tradition (but not modern scholarship) says that on this island he wrote the Apocalypse, or Book of Revelation, based on visions he experienced there.

The youngest of the Apostles, the Evangelist survived all of the Apostles and lived to the ripe old age of about 101. As his end neared, according to the Golden Legend,Jesus appeared and called him. John had a grave dug near the altar of his church and then, as in the miniature, walked into it. He said a prayer, a bright light surrounded him, and the saint vanished, leaving the grave filled with manna.

In the lower margin of fol. 174, John blesses the poisoned cup, from which serpents slither. Across a narrow body of water is the seven-headed beast of the Apocalypse. (Feast day: December 27)

After Domitian's death (A.D. 96), John went to Ephesus. There Aristodemus, high priest of Diana, challenged him to drink a cup of poisoned wine as a test of his God's strength. John blessed the cup, and the poison departed in the form of a serpent.

John the Evangelist

In the first year of his teaching, Christ called John the Evangelist (son of Zebedee) and his younger brother, St. James the Elder, while they were mending their fishing nets on the Sea of Galilee. Originally disciples of John the Baptist, they became followers of Jesus. John witnessed the Transfiguration and the Agony in the Garden with Peter and James, and was the "beloved disciple" who fell asleep on the bosom of Christ at the Last Supper. The only disciple not to forsake the Savior during the Passion, he was made the guardian of Jesus' mother, Mary, and was thought to have cared for her until her death.

MS H.8, fols. 174v–175r

Sts. Peter and Paul: Fall of Simon Magus

Hours of Henry VIII

Illuminated by Jean Poyer

Gift of the Heineman Foundation, 1977

Sts. Peter and Paul: Fall of Simon Magus

Border: Decapitation of Paul and Crucifixion of Peter (fol. 175)

According to the Apocryphal Acts of Peter, there was a sorcerer in Jerusalem named Simon Magus who proclaimed himself the source of truth and promised immortality to his believers. He confronted Peter to prove that he was God, but the Apostle refuted and exposed him. So the sorcerer went to Rome and gained Nero's support. Simon called the people together and declared that he was offended by the presence of Peter and Paul in the city; he threatened to abandon Rome and ascend into heaven.

Even without attributes, it is possible to distinguish between Peter and Paul by their appearance. Peter traditionally has a square, bald head with a short rectangular beard and Paul a bulbous forehead, narrow chin, and a long beard. (Feast day: June 29)

Climbing a tower, Simon Magus rose in flight, while Nero accused the two Apostles of being imposters. Peter, pointing out the flying sorcerer to Paul, cried out, "Angels of Satan, who hold this man up in the air, in the name of my Master Jesus Christ, I command you to hold him up no longer!" As shown in the miniature, they obeyed and Simon promptly plunged to his death. The disgruntled emperor then cast the two saints into prison, condemning them to death.

In the border Poyer illustrated the Decapitation of Paul and Crucifixion of Peter. Although their executions did not occur at the same location, they are often depicted together, as in this margin, since they happened (and are thus commemorated) on the same day.

Peter

Simon Peter, another fisherman turned Apostle, was known as the "rock of the Church." The Gospels record Christ's words to him, "Thou art Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church, and the gates of Hades shall not prevail against it; I will give unto thee the keys of the kingdom of Heaven." These words are also the source for Peter's attribute, a large key. One of the three apostles who witnessed Christ's Transfiguration, he traveled to Antioch after the Resurrection and preached the Gospel until A.D. 42. Peter was the first bishop of Rome and suffered martyrdom there. Nero ordered his crucifixion on 29 June 64, in his circus below Vatican Hill. Considering himself unworthy to die as Jesus had, the saint insisted upon being crucified head downward.

Paul

Paul, formerly a Greek-Jewish tent maker named Saul, was a strict Pharisee and persecuted the young Christian Church fanatically until an apparition of the resurrected Christ on the road to Damascus converted him. After he returned to Rome, he was beheaded by Nero on the road to Ostia, on the same day as Peter's martyrdom.

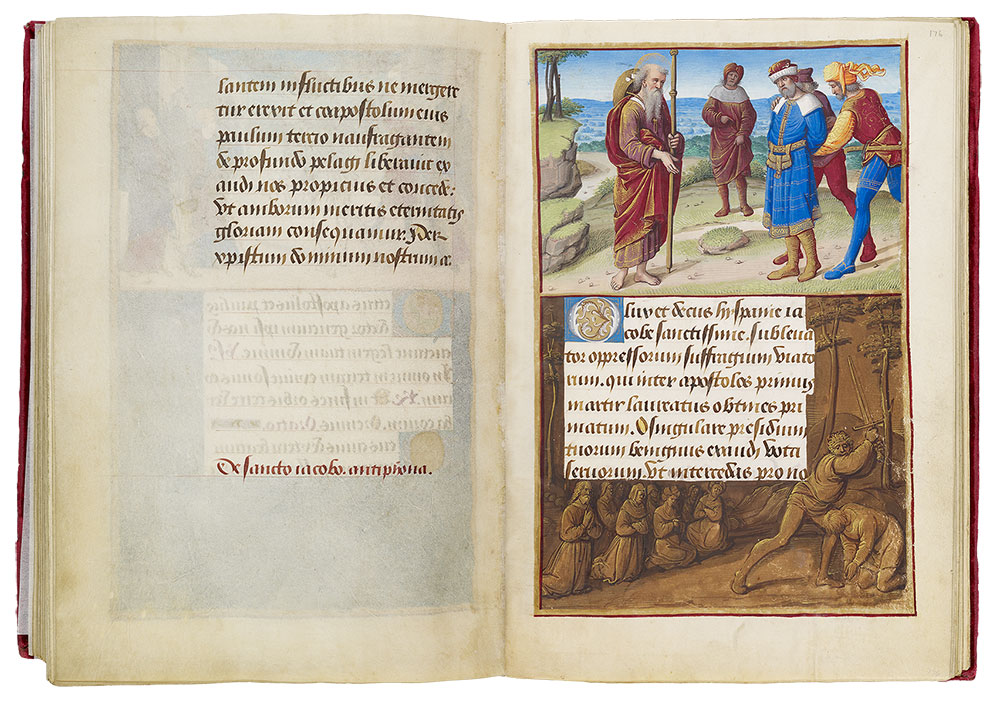

MS H.8, fols. 175v–176r

St. James: St. James with Hermogenes

Hours of Henry VIII

Illuminated by Jean Poyer

Gift of the Heineman Foundation, 1977

St. James: St. James with Hermogenes

Border: Decapitation of James (fol. 176)

James the Greater, or Elder (he was the older of two Apostles named James), was the brother of John the Evangelist. Here Poyer rendered the demons holding Hermogenes as exotically dressed soldiers, while the converted Philetus looks on. The terrified magician repented and promised to destroy his magic books.

After Christ's Ascension, James preached in Judea and Samaria, and then went to Spain. When he returned to Judea, the Pharisees requested that the magician Hermogenes should send his disciple, Philetus, to confront and refute the saint.

St. James performed some miracles, resulting in the conversion of Philetus and the rage of Hermogenes, who then ordered two demons to capture James and Philetus. Warned of the plot, the saint prayed that the demons bind and deliver Hermogenes instead, which they did.

The terrified magician repented and promised to destroy his magic books. Afraid of the demons, Hermogenes asked for something that belonged to the saint to prevent their attack, so James gave him his staff; when the converted magician returned with his tomes, the Apostle threw them into the sea.

The disappointed Pharisees dragged the saint before Herod Agrippa, who condemned him to be beheaded (A.D. 43). In the margin a crowd of kneeling men and women witness James's decapitation. This story apparently was modeled on that of Peter and Simon Magus in the preceding narrative.

James's Decapitation

After James's death, angels transported his body to Spain, where it lay on a stone that closed over it. His relics were discovered in the year 800 and taken to Compostella, which became a major pilgrimage site in the Middle Ages.

Pilgrims would return with badges as souvenirs, especially scallop shells (see also M.50 fol. 3); these were valued and often handed down as legacies. By the late Middle Ages, the saint himself was depicted as a pilgrim—his costume including a satchel decorated with a shell, a large hat, a traveler's cape, and staff; in the miniature two scallop shells decorate James's hat. (Feast day: July 25)

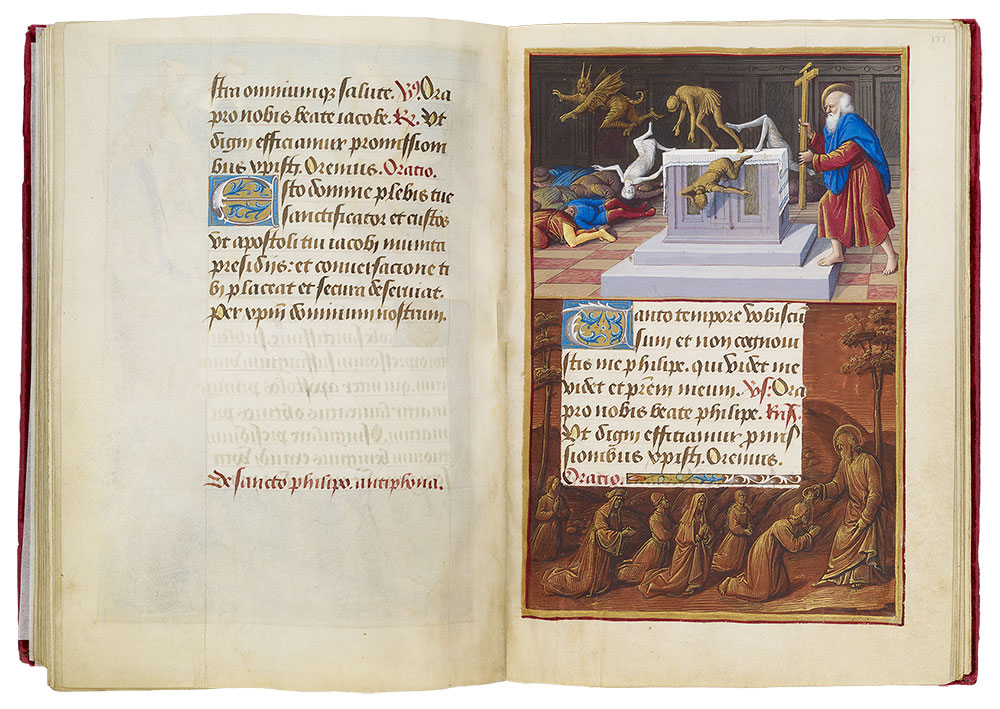

MS H.8, fols. 176v–177r

St. Philip: Philip Vanquishing Idols and a Demon

Hours of Henry VIII

Illuminated by Jean Poyer

Gift of the Heineman Foundation, 1977

St. Philip: Philip Vanquishing Idols and a Demon

Border: Philip Baptizing (fol. 177)

Philip, a native of Bethsaida in Galilee and a married father of three, gave up everything to follow Jesus. In the Apostle's most famous miracle, he cast the Devil, in the form of a hideous dragon, out of a statue of Mars.

Statue of Mars

A group of Scythian pagans had attempted to force the saint to sacrifice to a statue of the god Mars, but a huge dragon suddenly emerged from the statue, slaying the son of the priest and the two tribunes who had arrested the saint. The beast's noxious breath of the sickened onlookers.

Poyer's miniature, however, depicts a horned demon (instead of the traditional dragon) fleeing from Philip, and four statues fall from the altar of Mars (the golden ones are men, the white ones women). Beneath the demon are the fallen bodies of the sick and wounded, soon to be restored to health.

Philip told the crowd that if they broke the statue and adored the Lord's Cross, the sick would be cured and the dead would be brought back to life. The crowd agreed, and the saint spoke to the dragon, sending it to a faraway desert. Philip then healed the injured and revived the dead, converting the entire city.

(Border) In this image the saint baptizes the first of a long line of new converts made as a result of the miracle. (Feast day: May 1)

MS H.8, fols. 177v–178r

St. Christopher: Conversion of Christopher

Hours of Henry VIII

Illuminated by Jean Poyer

Gift of the Heineman Foundation, 1977

St. Christopher: Conversion of Christopher

Border: Christopher Carrying Christ (fol. 178)

The miniature portrays the moment when St. Christopher embraced Christianity, acknowledging the Cross's power with a reverential glance and gesture. The Devil, on horseback, gallops away in terror.

The name Christopher, which means "Christ-bearer" seems to suggest the basis of the saint's legend. As a Canaanite named Reprobus before his baptism, Christopher was a fearsome giant of a man.

Deciding to serve only the most powerful lord on earth, Christopher became a follower of Satan. However, the Devil fled upon seeing a crucifix planted in the roadway. Seeing Satan's fear, the giant resolved to follow Christ and his Cross instead.

In the margin, with the young Christ Child perched on his back, the saint struggles to cross the raging river. He leans heavily on his staff, panting with exertion. On the opposite bank is his mentor, the old hermit, who holds a lantern to light the way. (Feast day: formerly July 14)

Christopher's Resolve to Follow Christ

A hermit subsequently instructed the newly baptized Christopher in the Christian faith and gave him the task of helping travelers across a river. One stormy night a child asked the saint's assistance in traversing the current. The child was so heavy on Christopher's back that he nearly did not manage to cross. On the opposite bank the child announced that he was Jesus and Christopher had just carried the weight of the entire world on his shoulders. As proof of this, the child commanded the saint to plant his staff in the ground, where the next day it would blossom with flowers and dates.

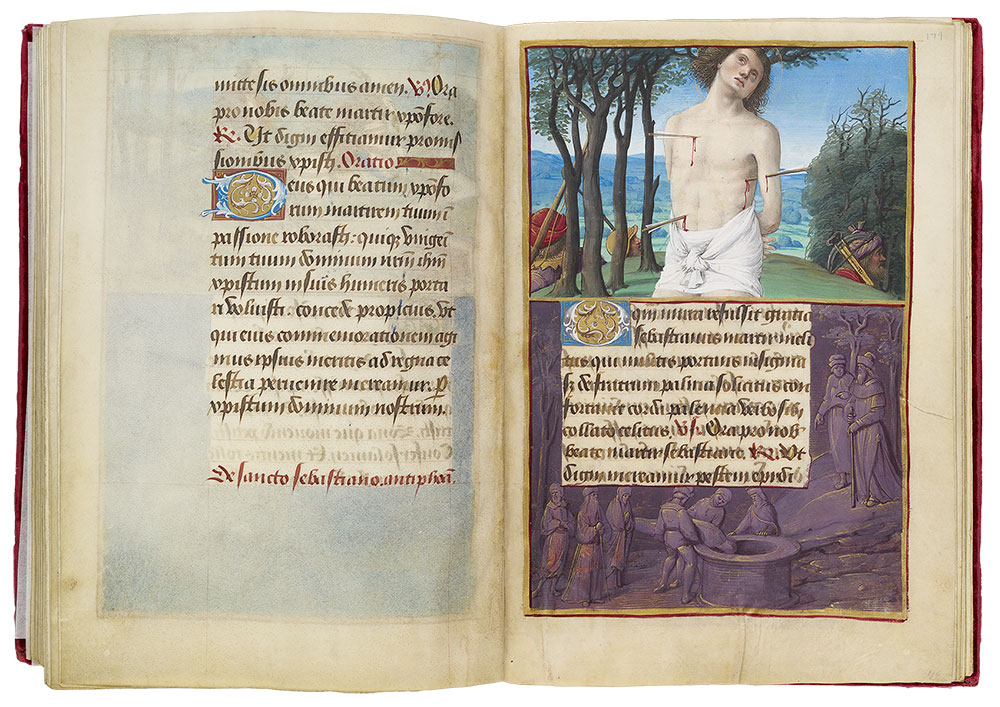

MS H.8, fols. 178v–179r

St. Sebastian: Sebastian Shot with Arrows, Abandoned by Archers

Hours of Henry VIII

Illuminated by Jean Poyer

Gift of the Heineman Foundation, 1977

St. Sebastian: Sebastian Shot with Arrows, Abandoned by Archers

Border: Sebastian's Body Cast into the Sewer (fol. 179)

During the late Middle Ages, Sebastian was usually depicted as a handsome, beardless youth, bound to a stake and pierced with arrows, his eyes looking heavenward. From the fifteenth century on he was nude (or nearly so).

Poyer's muscular Sebastian, his eyes turned upward, and clothed in a loincloth, is based on an Italian model. (Feast day: January 20)

In the lower margin two men dump Sebastian's shrouded body into the sewer. To the right a figure leaning on his staff, probably the emperor, oversees the operation, while at the left three Christians, including the matron Lucina, wait to reclaim the body.

St. Sebastian

According to legend, Sebastian was born in Gaul and raised in Milan. Although a Christian, he joined the Roman army in 283, rising to captain in the Praetorian Guard under Emperor Diocletian. Sebastian clandestinely assisted and consoled imprisoned Christians in addition to converting and baptizing other soldiers and civilians. His own religious convictions remained a secret until the tortures inflicted on his Christian friends Marcus and Marcellinus so infuriated him that he publicly proclaimed his faith. He was then condemned to die as a target for archery practice. After the attack a pious widow, Irene, claimed the body but discovered that Sebastian was still alive. She nursed him back to health, and he returned to the palace to confront the emperor. Diocletian promptly ordered Sebastian beaten to death and the body dumped into the Cloaca Maxima, the main sewer of Rome, preventing Christians from preserving and venerating it as the relic of a martyr. On the following night, however, the saint appeared to a Roman matron, St. Lucina, revealing the location of his body, which was subsequently retrieved and interred in the catacomb on the Appian Way.

MS H.8, fols. 179v–180r

Hours of Henry VIII

Illuminated by Jean Poyer

Gift of the Heineman Foundation, 1977

MS H.8, fols. 180v–181r

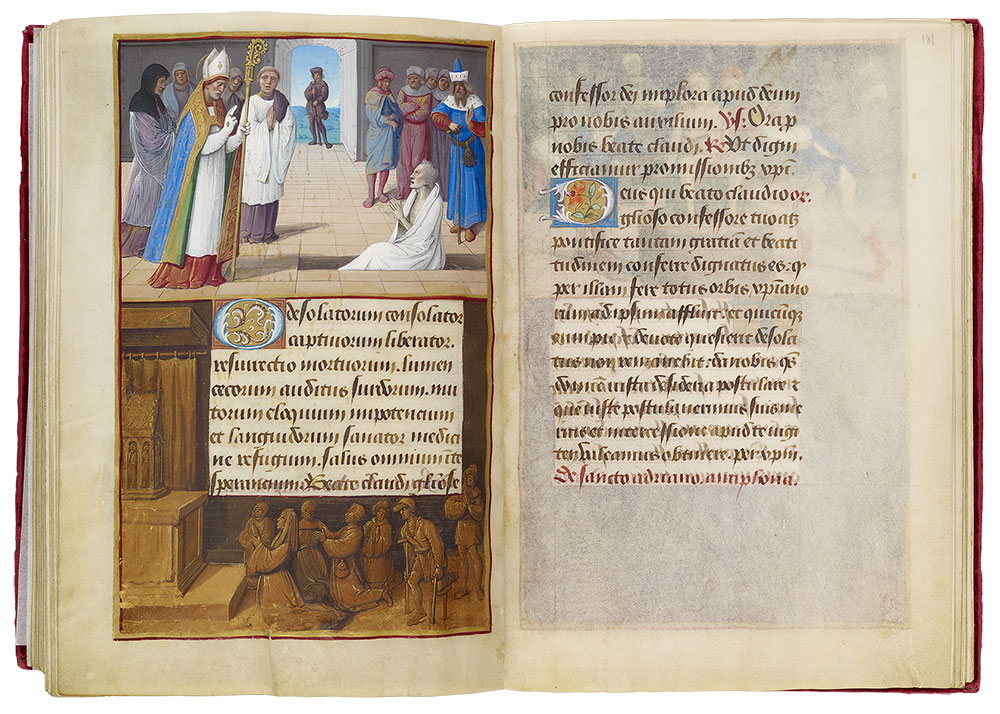

St. Claude of Besançon: Claude Resuscitating a Dead Man

Hours of Henry VIII

Illuminated by Jean Poyer

Gift of the Heineman Foundation, 1977

St. Claude of Besançon: Claude Resuscitating a Dead Man

Border: Pilgrims Kneeling Before Claude's Shrine (fol. 180v)

Claude, as in the miniature, is usually depicted as a bishop with miter and crosier. Here, as a result of his blessing, a dead man sits up in his grave, newly restored to life. (Legends often mention a dead child.)

Born at Salins in 607, Claude of Besançon was said to be from a Roman senatorial family. At the age of twenty he gave up a military career to become canon of Besançon; later he became a monk at the monastery of St. Oyend in the Jura Mountains, where he was subsequently elected abbot. As abbot, Claude applied the rule of St. Benedict and restored the monastery's buildings. In 685 he was chosen bishop of Besançon but retired eight years later to Condate, where he later died and was buried (6 June 699). His burial place (later called Saint-Claude) was a popular pilgrimage site, and miraculous cures took place there, including the resuscitation of three drowned children and a dead boy.

In the margin a group of pilgrims worships before the jewel-encrusted shrine containing the saint's relics. A woman in contemporary court dress kneels in front. Claude was often prayed to by French nobility for the birth of sons. At the rear hobbles a lame man, hoping for his eventual cure. (Feast day: June 6)

MS H.8, fols. 181v–182r

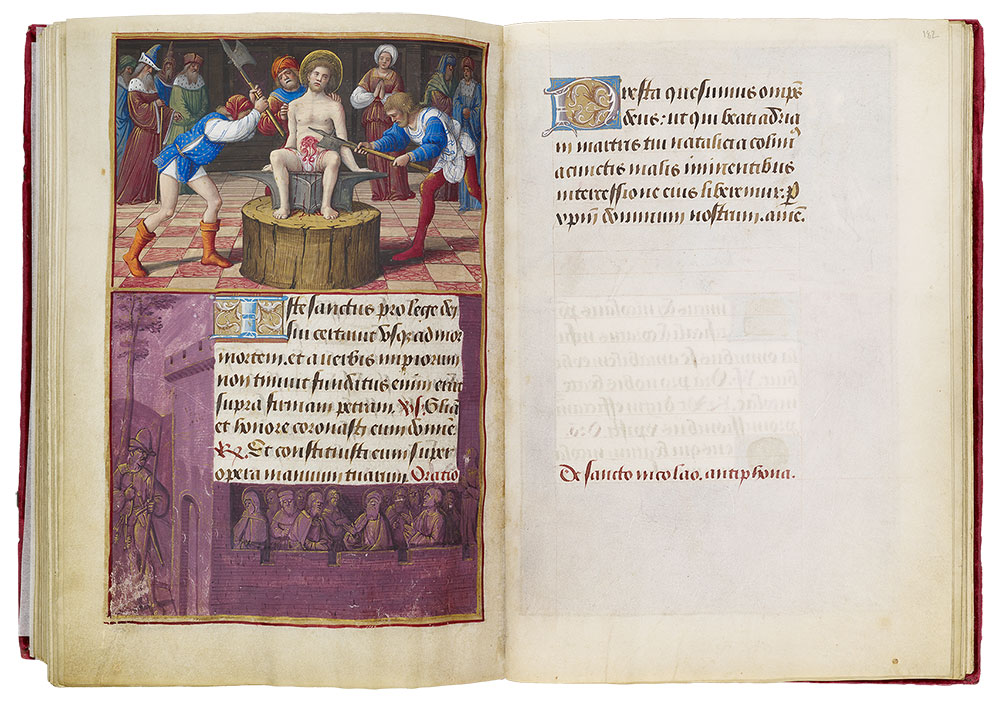

St. Adrian: Martyrdom of Adrian

Hours of Henry VIII

Illuminated by Jean Poyer

Gift of the Heineman Foundation, 1977

St. Adrian: Martyrdom of Adrian

Border: Christians in Prison (fol. 181v)

The miniature shows Adrian's two-part martyrdom. He is seated on the anvil, his intestines having already fallen out, as two executioners begin to hack off his legs. Adrian looks heavenward, while in the background Natalia prays contentedly; the emperor, at the left, directs the torture.

Adrian (or Hadrian) was a young Praetorian Guard in Nicomedia under Emperor Maximian (r. 286–305). The soldier was converted by witnessing the steadfast confidence of a group of Christians under torture. Impressed by their constancy, he asked to be counted among their ranks. Needless to say, Adrian was promptly arrested and imprisoned. His new wife, Natalia, (a secret Christian) was overjoyed, ran to the prison, and encouraged him to remain firm in his new faith, kissing his chains. When he learned the date of his impending martyrdom, the saint convinced the guards to allow him to tell his wife so that she could witness the event.

On the day of his death (ca. 300), Adrian was first beaten so severely that his "bowels fell out." After he was returned to prison, the emperor ordered that the legs of all the imprisoned martyrs be broken on an anvil and cut off. Natalia, who was present, additionally requested that the guards cut off her husband's hands, so that he would be equal to other saints who had suffered more. After Adrian's death Natalia managed to get away with a hand (holding it to her bosom), taking it with her to Argyropolis, where she died peacefully.

In the margin a jailer guards the imprisoned Christians who prompted Adrian's conversion. (Feast day: September 8, the translation of his relics to Rome)

MS H.8, fols. 182v–183r

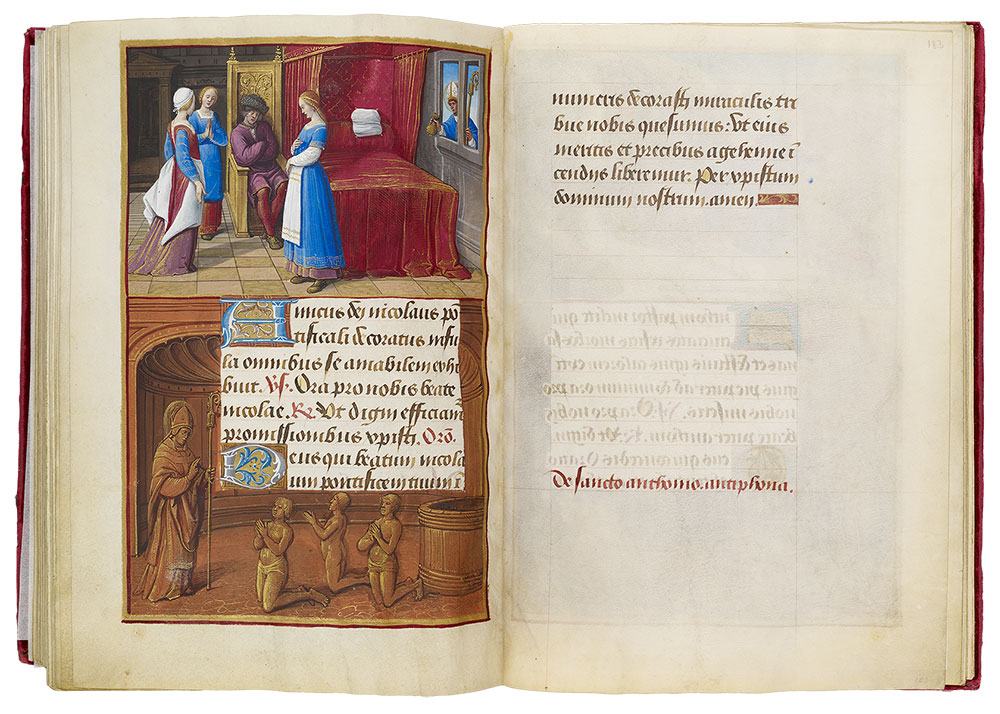

St. Nicholas: NIcholas Giving Gold to the Three Maidens

Hours of Henry VIII

Illuminated by Jean Poyer

Gift of the Heineman Foundation, 1977

St. Nicholas: NIcholas Giving Gold to the Three Maidens

Border: Nicholas Resuscitating the Three Boys (fol. 182v)

Nicholas (of Myra or Bari), one of the most universally venerated saints, is said to have been born about 270 and died in 342. A precociously religious child of wealthy parents, Nicholas supposedly stood up and praised God the moment he was born. When he inherited his father's fortune, he gave it away to the poor.

In the miniature the saint appears at a double window holding a bag of gold near a bed, while the girls' despondent father slumps in a chair. (The three gold balls became the insignia for the pawnbroker.)

St. Nicholas's most celebrated act of generosity occurred upon hearing an impoverished neighbor lament that he could not supply dowries for his three daughters, leaving them no alternative but a life of prostitution. On three successive nights Nicholas threw a bag of gold (or a gold ball) through their window.

The saint's second famous miracle involves an unscrupulous innkeeper who, during a food shortage, dismembered and pickled three young boys to feed his guests. Sensing foul play, Nicholas made the Sign of the Cross over the tub, and the three stood up, restored to life.

In the grisaille border the three boys, now restored to life, kneel in gratitude before the blessing saint. This legend may have developed from the three purses or gold balls normally shown with the saint, which were mistaken for the towheads of children.

As Nicholas's feast falls during the Christmas season, he was confused with a folklore character who rewarded good children with gifts brought secretly during the night. The two eventually merged to become Father Christmas, or Santa Claus (Feast day: December 6)

MS H.8, fols. 183v–184r

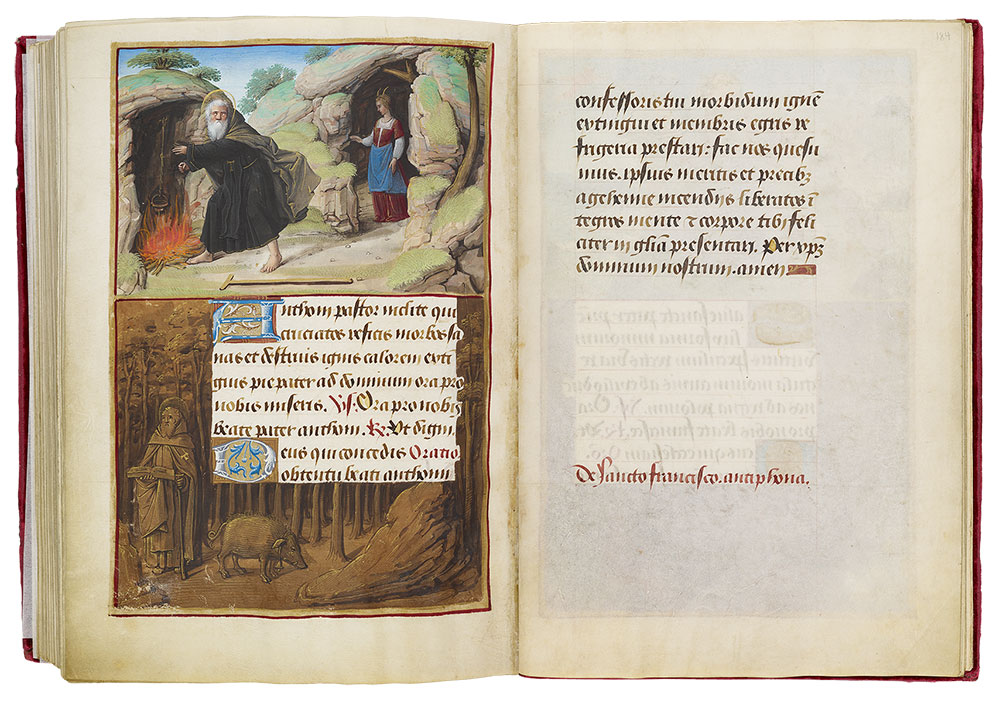

St. Anthony Abbot: Temptation of Anthony

Hours of Henry VIII

Illuminated by Jean Poyer

Gift of the Heineman Foundation, 1977

St. Anthony Abbot: Temptation of Anthony

Border: Anthony in the Wilderness (fol. 183v)

Anthony Abbot, or Anthony the Great (ca. 251–356), is best known for his long life of asceticism in the Egyptian deserts. Born in an Egyptian village near Memphis, Anthony Abbot decided at age twenty, when his parents died, to become a hermit. For two decades the saint lived in complete solitude in an abandoned tomb. Here the Devil tempts him in the form of an attractive woman, and scares him in the forms of a black man and then wild animals.

In 1095, in La Motte (in southern France), an order of Hospitalers was created in the saint's honor. Wearing black robes with a blue tau cross, they traveled widely, ringing bells for alms. By special ordinance, the Hospitalers' pigs were allowed to forage freely, leading to pictures of the saint accompanied by a pig.

Poyer's miniature presents Anthony as an old bearded man in a black robe and tau cross (the Egyptian cross and a symbol of his abbatial authority). The crutch at the saint's feet refers both to Christ's Cross and to the Hospitalers' care of the infirm. Anthony reaches toward the fire to escape the demonic young woman (note her horns).

In the margin below Anthony appears with his staff in the wilderness; the open book symbolizes the book of nature, which compensated the saint for lack of any other reading material. The belled pig at his side refers to the order of Hospitalers, but it was also his only companion in the wilderness. (Feast day: January 17)

MS H.8, fols. 184v–185r

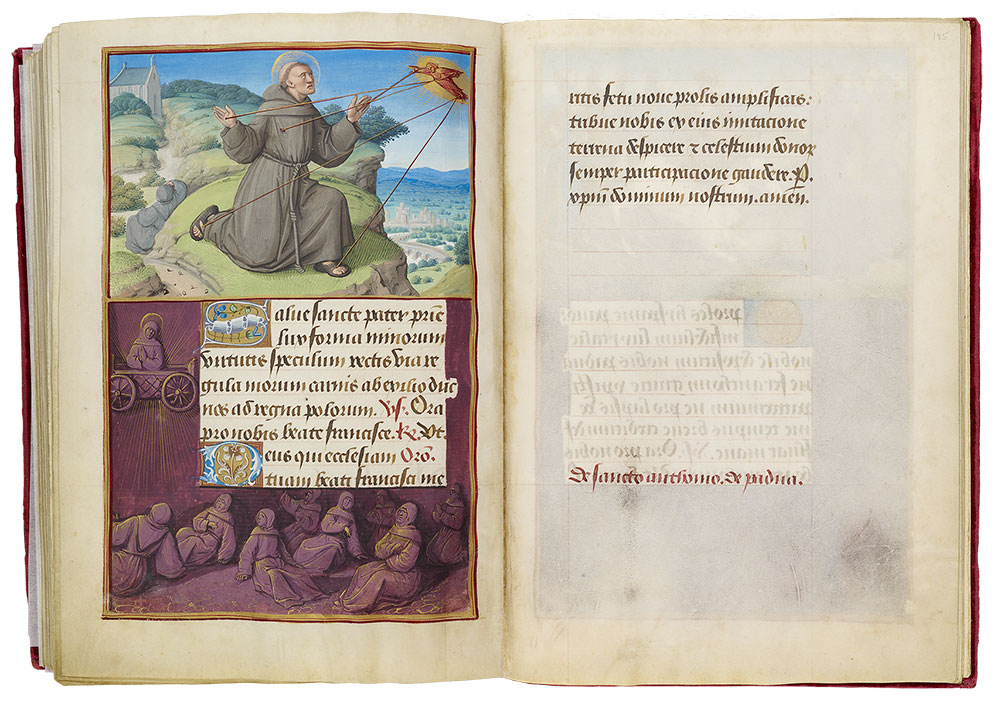

St. Francis: Stigmatization of Francis

Hours of Henry VIII

Illuminated by Jean Poyer

Gift of the Heineman Foundation, 1977

St. Francis: Stigmatization of Francis

Border: Francis in the Fiery Chariot (fol. 184v)

A great deal is known about the life of Francis of Assisi (118–1226), the founder of the Order of Friars Minor (Franciscans). As a youth he led the life of a carefree cavalier, but a year spent as a prisoner of war in Perugia (1201) and a subsequent serious illness changed Francis's values, leading him to become a monk devoted to the care of the poor and lepers. In 1210 the saint, with a dozen followers, traveled to Rome, petitioning Pope Innocent III to establish his new order, the brotherhood of poverty. The order was created and grew rapidly.

On 14 September 1224, while on retreat at Mount Alvernia, Francis prayed that he might feel with his own body the agony of Christ on the Cross and was rewarded with the stigmata, which he hid from others until his death. The event, appropriately, occurred on the feast day of the Exaltation of the True Cross. Francis died two years later; he was canonized by Pope Gregory IX (r. 1227–41) in 1228.

The miniature shows the moment of stigmatization. Francis kneels in prayer on a mountaintop before the apparition of a seraph who folds his wings to form the shape of a cross. Five rays project from the angel, marking the saint in the same places as Christ's wounds (as also shown in the left border of fol. 5v).

Francis wears the gray habit of his order with a cord for a belt. The knotted belt is a reminder of the cords that bound Christ; the three knots symbolize the three Franciscan virtues of poverty, chastity, and obedience.

At the left is one of the three monks who went with Francis to the mountaintop but slept through the event.

The grisaille scene depicts an obscure miracle—derived from Elijah's chariot of fire—that was popularized during the fourteenth century. Francis, concerned that his monks had been lax, appeared to them in a floating fiery chariot, reminding them tofollow his rules of poverty and humility. The apparition awakens the monks, some of whom are still befuddled by sleep; two in the right rear, however, kneel in prayer. (Feast day: October 4)

MS H.8, fols. 185v–186r

St. Anthony of Padua: Anthony and the Miracle of the Kneeling Horse

Hours of Henry VIII

Illuminated by Jean Poyer

Gift of the Heineman Foundation, 1977

St. Anthony of Padua: Anthony and the Miracle of the Kneeling Horse

Border: Anthony Preaching (fol. 185v)

One of Anthony's most popular miracles involved a challenge to prove the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist. Although the story is normally told about a mule, Poyer has replaced it with a horse, who ignores the proffered feed and kneels before the host that Anthony holds over a chalice.

Born in Lisbon in 1195, the saint is known as Anthony of Padua because the basilica in that city (where he briefly resided) possesses his miracle-working relics. Already, as a pious youth, he used prayer to overcome the severe temptations against purity that he suffered during his teens. Initially joining the Augustinian order, he later became a Franciscan friar and preached throughout northern Italy and southern France with great success.

Anthony died in 1231 at Arcella, near Padua, and was quickly canonized by Pope Gregory IX the following year. Until the end of the fourteenth century his cult was a local Paduan phenomenon. However, in the fifteenth century, Bernardino of Siena, a noted theologian and leader of the Franciscan order, brought Anthony wider renown, making him the most popular Franciscan saint after Francis of Assisi.

An unbelieving man, a Jew named Guillard, looks on in astonishment, as he had claimed that he would be convinced if a horse could pass up a measure of oats for the consecrated Host. (Feast day: June 13)

Having a magnificent memory and vast knowledge of the Bible, Anthony and was acclaimed for his skill in preaching, which began when a misunderstanding at an ordination left the service without a speaker. His superiors ordered him to come forward and say whatever the Holy Spirit put into his mouth, which he did with great style, passion, and erudition.

MS H.8, fols. 186v–187r

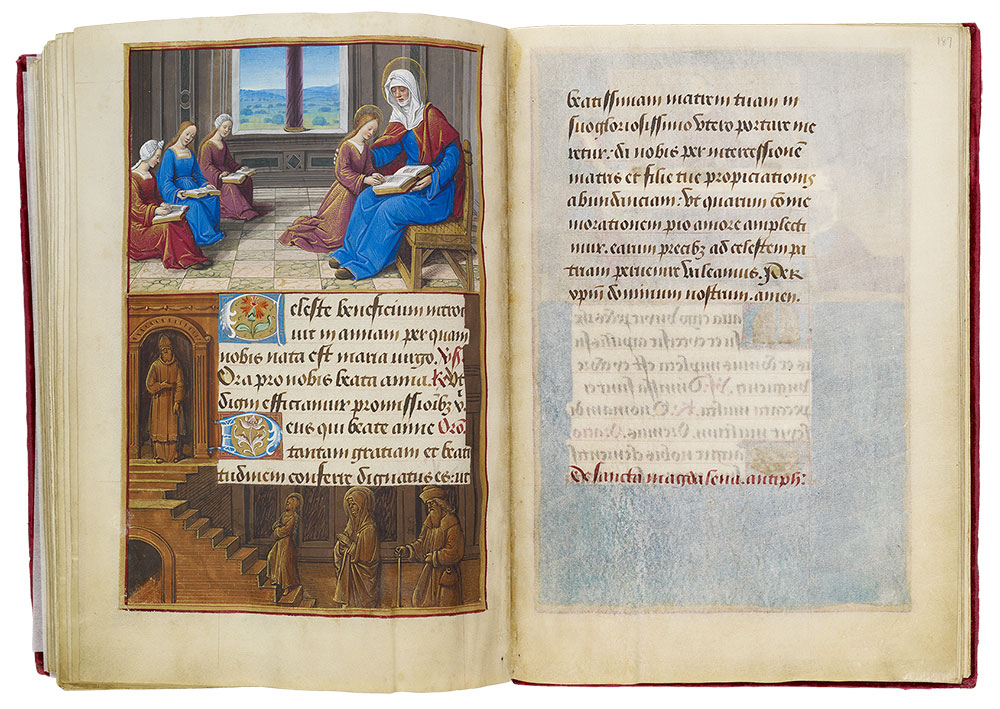

St. Anne: Anne Instructing the Virgin

Hours of Henry VIII

Illuminated by Jean Poyer

Gift of the Heineman Foundation, 1977

St. Anne: Anne Instructing the Virgin

Border: Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple (fol. 186v)

In the later Middle Ages (with its increased literary levels) Anne is often depicted, as here, instructing the Virgin in her reading. The scene takes place in a domestic interior that also includes other students, but Mary is distinguished by her primacy as well as her halo.

According to the apocryphal Gospel of James, the Virgin Mary's parents, Anne and Joachim, were an elderly and childless couple. An angel answered their prayers for a child, telling them that their offspring would become famous. Anne vowed to dedicate the infant Mary to the Lord, and at the age of three, the girl was presented in the temple, where she was raised in the service of God. Once Mary was old enough to marry, the priests sent her home so that she might find a husband.

According to the Golden Legend, Anne married twice after Joachim's death: first to Cleophas and then Salome, bearing a daughter named Mary to each of them. Each of her daughters named Mary, respectively, bore one, four, and two sons, making Anne the grandmother of Jesus; Sts. Simon, Jude, Joseph the Just, and James the Less; and Sts. John the Evangelist and James the Great.

The Prayer Book of Anne de Bretagne (see also M.50), also illustrated by Poyer, includes a Suffrage (different from the one here) mentioning Anne's trio of husbands; the accompanying illustration also depicts St. Anne instructing the Virgin (M.50, fol. 13). (Feast day: July 26)

Poyer's border depicts Mary's presentation at the Temple. The three-year-old child, followed, but not assisted, by Anne and Joachim, has begun to climb the fifteen steps leading to the temple. Zacharias, priest and father of John the Baptist, waits to receive her in the doorway.

MS H.8, fols. 187v–188r

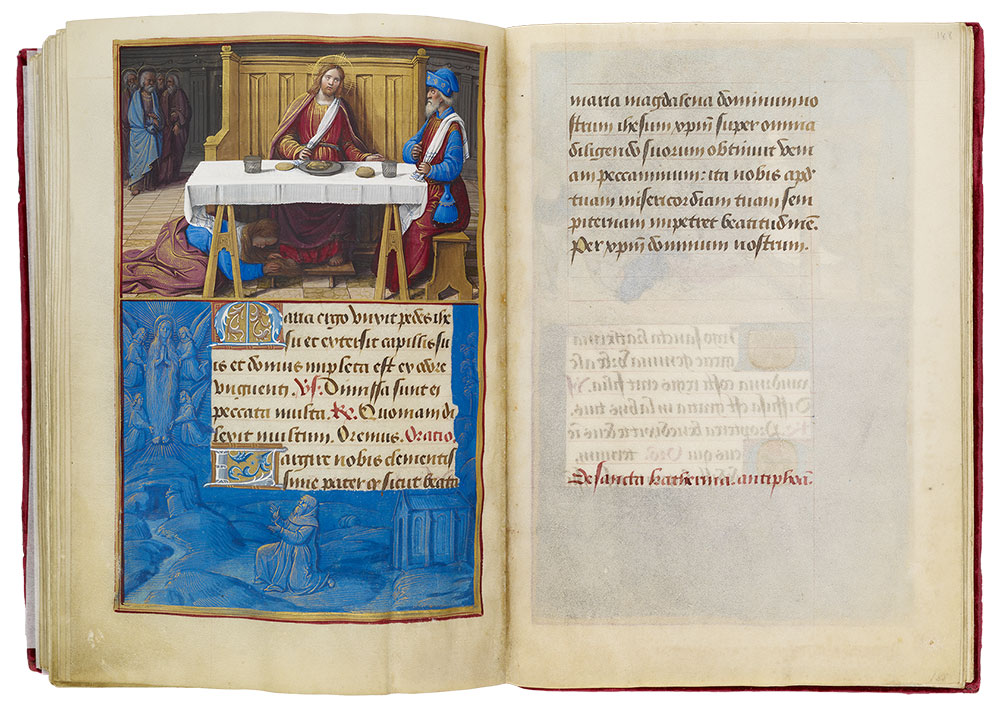

St. Mary Magdalene: Mary Magdalene Washing the Feet of Christ

Hours of Henry VIII

Illuminated by Jean Poyer

Gift of the Heineman Foundation, 1977

St. Mary Magdalene: Mary Magdalene Washing the Feet of Christ

Border: Levitation of Mary Magdalene (fol. 187v)

In the miniature of Christ's dinner at Simon's house, the Magdalene dries Christ's feet with her long, flowing hair, while the Savior leans to the Pharisee, who is stiff with indignation, and defends her actions. At the left, the Apostles huddle together in disapproval.

The legend of Mary Magdalene, the archetypal repentant woman sinner, is a conflation of three New Testament persons: Mary of the village of Magdala from whom Jesus drove seven devils; Mary of Bethany, sister of Lazarus and Martha; and the un- named sinner at Simon the Pharisee's (or Leper's) house who washed Christ's feet with her tears and then anointed them. Be that as it may, Mary Magdalene witnessed Christ's Crucifixion, prepared his body for burial, and was the first witness to his Resurrection. Mary Magdalene is depicted in The Prayer Book of Anne de Bretagne.

The immobilized hermit witnessing Mary's celestial feeding is shown in the border. The iconography of her ascension via angels, begun in the twelfth century, is based on the Assumption of the Virgin. The Magdalene's hair, which has grown to her feet, covers her body. (Feast day: July 22)

After Christ's Ascension, according to an eleventh-century Provençal legend recorded in the Golden Legend, Mary, with Sts. Martha and Lazarus, was cast adrift in a rudderless boat by infidels; guided by an angel, however, they reached Marseilles, France. After a period of preaching, Mary retired to the cave of Sainte-Baume in the Maritime Alps, passing thirty years in penitence and contemplation. Never eating, she was refreshed by the songs of the heavenly hosts, which she heard when angels carried her aloft every day at the canonical Hours. On one occasion, a hermit, who had built a cell near her grotto, witnessed the angels lifting and returning the saint to earth. Wanting proof of what he had seen, he ran to where she appeared but was paralyzed. The saint then revealed her identity.

MS H.8, fols. 188v–189r

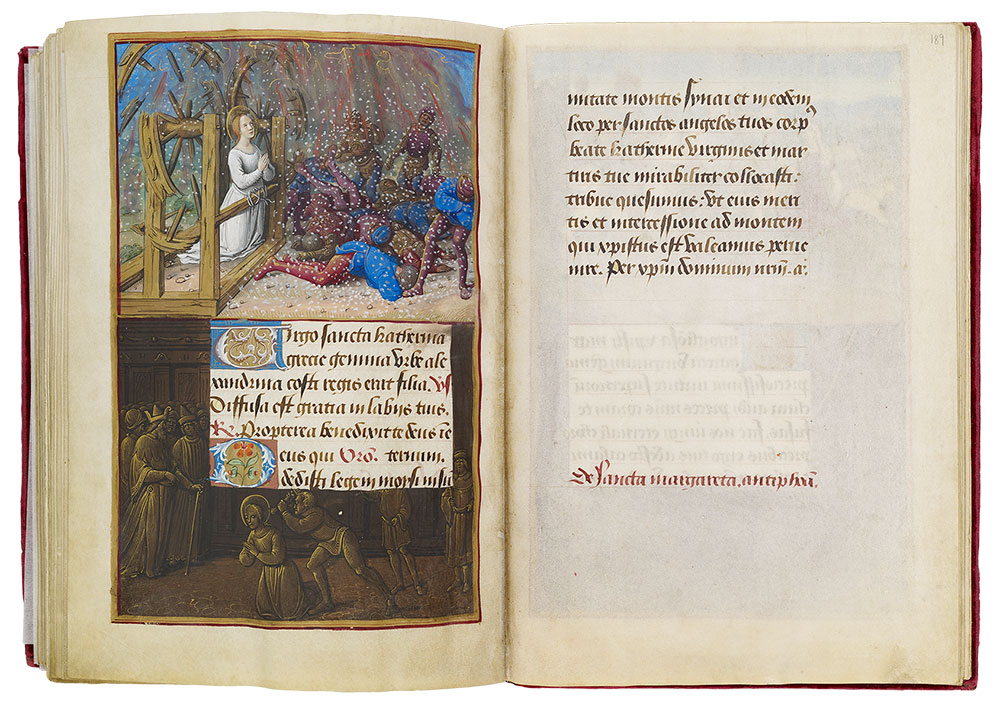

St. Catherine: Catherine Rescued from the Torture Wheels

Hours of Henry VIII

Illuminated by Jean Poyer

Gift of the Heineman Foundation, 1977

St. Catherine: Catherine Rescued from the Torture Wheels

Border: Decapitation of Catherine (fol. 188v)

According to the Golden Legend, Catherine was the daughter of King Costas of Cyprus. Renowned for her noble birth and education, she attracted the interest of the early- fourth-century Emperor Maxentius (r. 306–12) who wanted to marry her. She refused him, having chosen instead to become the "bride of Christ."

Catherine's steadfast refusal of the emperor led to the order for her execution. Two spiked wheels, which were to grind against each other, were constructed, and the saint was placed between them. She prayed to the Lord for the machine to fall to pieces so that his name would be praised and those who stood by might be converted. Instantly an angel struck thedevice with such violence it broke apart, killing her tormentors.

Believing he could force the young woman to apostatize, Maxentius gathered fifty prominent pagan philosophers in Alexandria to convince her of the errors of Christianity. Shesuccessfully refuted them and even converted the philosophers, who were subsequently executed. Catherine, however, was unharmed, as the emperor still lusted after her.

The spurned emperor ordered Catherine beheaded, the subject depicted in the margin. Maxentius, holding a staff, looks on as the executioner prepares to do his job (his sword is hidden by the text).

At her death, Catherine prayed to Jesus that "whosoever shall celebrate the memory of my passion, or shall call upon me at the moment of death or in any necessity, may obtain the benefit of thy mercy," increasing the popularity of her cult and ensuring the efficacy of her intercession. After Catherine's death, angels carried her body to Mount Sinai, where it is preserved in the famous monastery that bears her name. (Feast day: formerly November 25)

MS H.8, fols. 189v–190r

St. Margaret: Margaret and Olybrius

Hours of Henry VIII

Illuminated by Jean Poyer

Gift of the Heineman Foundation, 1977

St. Margaret: Margaret and Olybrius

Border: Margaret and the Dragon (fol. 189v)

Margaret was the daughter of Theodosius of Antioch, a third-century pagan prince. Shortly after Magaret's birth, her mother died, so her father placed her in the care of a countrywoman, a secret Christian who raised the young girl in that faith. Later, after Margaret's conversion was discovered, she was disowned and banished with her nurse from the palace. They lived in the country as shepherdesses.

One day Governor Olybrius of Antioch, as in the miniature, saw Margaret spinning wool while tending sheep and fell in love with her. Margaret's refusal to yield her faith angered the governor.

Olybrius ordered Margaret tortured and thrown into prison, where a fierce dragon appeared and swallowed her. The saint made the sign of the Cross, causing the dragon to explode, freeing her from its belly. She then prayed that women in labor invoking her name would be as safely delivered as she was from the dragon.

During the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, Margaret was most frequently shown guarding sheep; later the prison scene with the dragon (her primary attribute) became popular. (Feast day: formerly July 20)

MS H.8, fols. 190v–191r

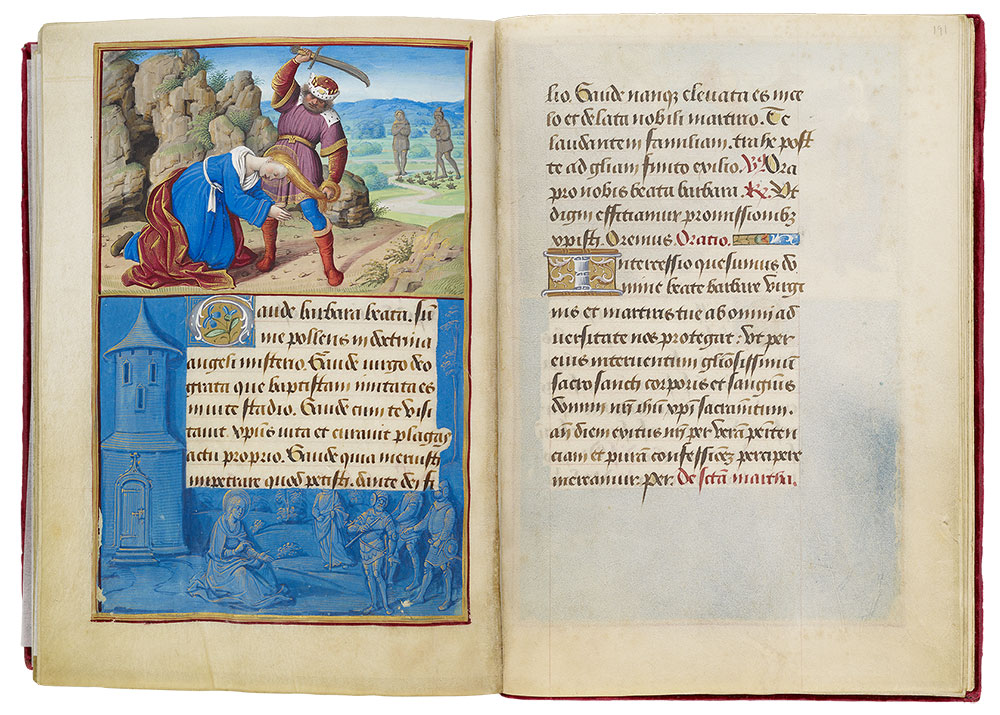

St. Barbara: Decapitation of Barbara

Hours of Henry VIII

Illuminated by Jean Poyer

Gift of the Heineman Foundation, 1977

St. Barbara: Decapitation of Barbara

Border: Barbara Before Her Tower (fol. 190v)

Legend has it that Barbara was the daughter of an Eastern governor, Dioscurus of Heliopolis, who imprisoned her in a two-windowed tower so that no man could see her. Seeking religious fulfillment she wrote to the Church father Origen (ca. 185–ca. 254), who sent his disciple Valentine to instruct her. Disguised as her doctor, he gained access to the tower and eventually baptized her.

Poyer depicted the two shepherds who saw Barbara fly up to a mountain, where they kept their sheep, and betrayed her. At their feet, their flock of sheep, through divine retribution, were transformed into insects. (Feast day: formerly December 4)

Dioscurus handed his daughter over to the Proconsul Marcian for torture, but she steadfastly refused to renounce Christianity. Out of anger and frustration, the governor dragged his daughter by the hair to the mountaintop and cut off her head.

When her father was away on a trip, Barbara had workmen add a third window—in honor of the Trinity—in her tower. Upon his return, she told her father that the three windows symbolized the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, who had illuminated her. Furious, Dioscurus forced her to take refuge at the top of her tower, from which angels carried her away to a secret hiding place.

MS H.8, fols. 191v–192r

St. Martha: Martha Taming the Tarasque

Hours of Henry VIII

Illuminated by Jean Poyer

Gift of the Heineman Foundation, 1977

St. Martha: Martha Taming the Tarasque

Border: Martha Preaching (fol. 191v)

Martha was the sister of Lazarus and Mary Magdalene. After Christ's Ascension, they were set adrift in a boat, which was guided by an angel to Marseilles.

In Marseilles, according to legend, Martha overcame a dragon, the Tarasque, which had been terrorizing the people of Tarascon in Provence. Half- animal and half-fish, the monster slew passersby and sank ships. The people appealed to Martha for help. Armed with an aspergillum (a device to sprinkle holy water) and holy water bucket, she went after the dragon, which she found devouring a man.

After subduing the beast with holy water, as in the miniature, she bound it about the neck with her girdle and led it away to be killed. One man plunges a spear into its neck while another—at a considerably safer distance— aims his crossbow.

Martha, devoting herself to prayer and fasting, remained in Tarascon, where a great community of religious women grew up around her. One day, while she was preaching on the bank of the Rhône River near Avignon, her second famous miracle occurred.

A young man on the opposite bank was eager to hear her words. Having no boat, he attempted to swim across, but he was overcome by the current and drowned (as shown in the border). After the body was recovered, it was laid at the saint's feet so that she might revive him. In her prayer she asked Christ, who had raised her brother Lazarus to life, to do the same for the dead youth. Taking the young man by the hand, she caused him to rise at once, and he was baptized. (Feast day: July 29)

MS H.8, fols. 192v–193r

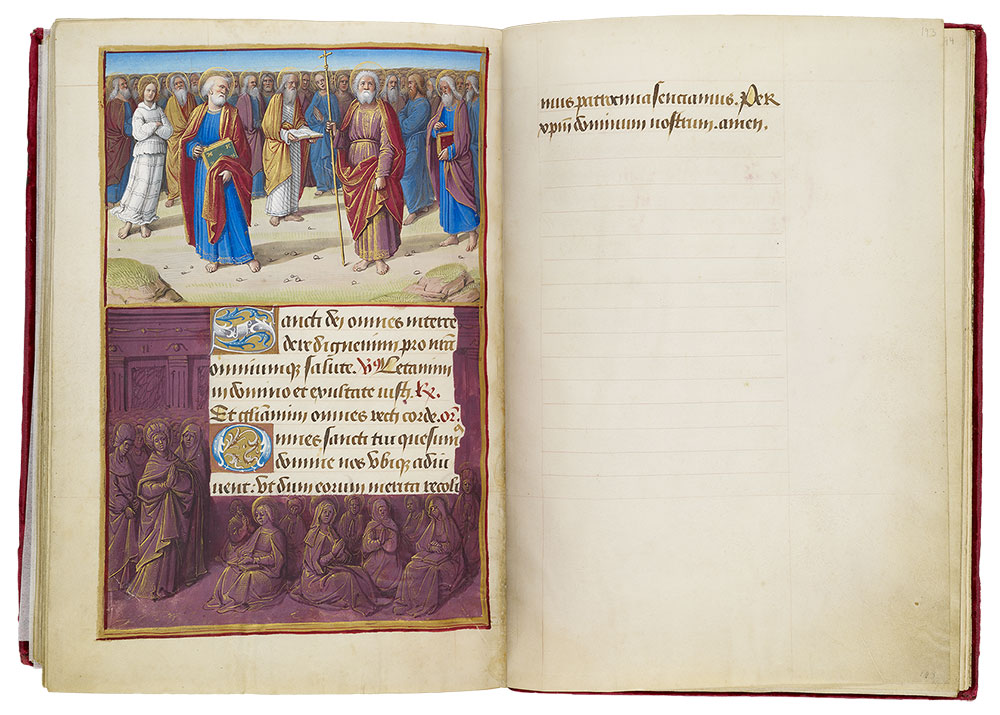

All Saints: All Male Saints

Hours of Henry VIII

Illuminated by Jean Poyer

Gift of the Heineman Foundation, 1977

All Saints: All Male Saints

Border: All Female Saints (fol. 192v)

All Saints was a catchall feast of Eastern origin, which celebrated the "martyrs of the whole world" on the first Sunday after Pentecost. (In the early Church all saints, with the exception of the Apostles, were martyrs.) Images of all saints typically show them in ranks. In accordance with a well-established hierarchy, the male saints out-ranked the females (hence the women's relegation to the margin).

During the last few years (ca. 303–5) of Emperor Diocletian's reign so many Christians were martyred that it became impossible for each to have his or her own assigned day for commemoration, hence this all-encompassing feast. With the dedication of the Pantheon in Rome to St. Mary of the Martyrs on 13 May 609 (or 610), the feast changed to that date. When Pope Gregory III dedicated a chapel on November 1 to All Saints in St. Peter's Basilica, the feast was changed to that day, where it has remained. According to the Golden Legend, the date was changed so that greater crowds could come to Rome after the harvest and vintage to participate in the popular celebration. In English the feast is known as All Hallows and the night before as Hallowe'en (short for All Saints' Eve).

Within the context of Suffrages in a Book of Hours, this massive grouping of saints serves an additional purpose. Praying to all the saints at once, encourages them to join in an intercession. Surely it would be impossible for God not to grant the prayers of all the saints on one's behalf. Little wonder that the feast day was such a favorite.

The male saints were further ordered by status: first came the Apostles, followed by martyrs, and then confessors. Poyer suggested these divisions by placing Peter and Paul at the head of the contingent. Close behind them are the four evangelists; the young man at left dressed in white is John, the beloved disciple. Behind them, the rest of the saints form an isocephalic horizon.

The women in the margin of the lower image, seated with books or praying, have no identifying attributes. (Feast day: November 1)