Innovations in Drawing

Technical and artistic innovations combined to make Renaissance Venice a vital creative center. Late-fifteenth-century artists generally worked in pen and ink and wash to make relatively finished drawings, but new techniques emerged that enabled them to produce more diverse, and often dramatic, effects. Artists such as Vittore Carpaccio perfected a method of applying ink with a brush onto Venetian blue paper (carta azzurra)—a support greatly prized by Albrecht Dürer. Artists of Titian and Bordone's generation, followed by Tintoretto, preferred a soft black chalk that was ideally suited to record tonal subtleties and create impressions of movement. Jacopo Bassano's innovative use of colored chalks made him a precursor to the pastel tradition. Tintoretto's younger contemporary, Veronese, developed entire compositions with rapid pen sketches while retaining a typically Venetian preoccupation with light.

Jacopo Tintoretto

Roman Head (So-Called Head of Emperor Vitellius)

Purchased as the gift of Mr. and Mrs. Carl Stern, 1959

This drawing depicts a Roman portrait bust sent to Venice by Cardinal Domenico Grimani and exhibited in the Ducal Palace from 1525 to 1593. Traditionally it was thought to represent the Roman emperor Vitellius, famous for his indolence and gluttony. A plaster cast of this antique sculpture was documented in Tintoretto's studio.

About twenty studies of this bust by Tintoretto and his pupils are known. The present version portrays the head from a low vantage point, emphasizing the massive neck and jowls, with vigorous parallel hatching and sharp highlights making the figure look particularly alive and dramatic.

Innovations in Drawing

Technical and artistic innovations combined to make Renaissance Venice a vital creative center. Late-fifteenth-century artists generally worked in pen and ink and wash to make relatively finished drawings, but new techniques emerged that enabled them to produce more diverse, and often dramatic, effects. Artists such as Vittore Carpaccio perfected a method of applying ink with a brush onto Venetian blue paper (carta azzurra)—a support greatly prized by Albrecht Dürer. Artists of Titian and Bordone's generation, followed by Tintoretto, preferred a soft black chalk that was ideally suited to record tonal subtleties and create impressions of movement. Jacopo Bassano's innovative use of colored chalks made him a precursor to the pastel tradition. Tintoretto's younger contemporary, Veronese, developed entire compositions with rapid pen sketches while retaining a typically Venetian preoccupation with light.

Jacopo Tintoretto

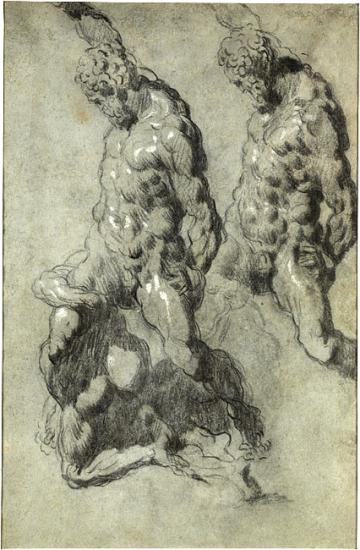

Two Studies of Samson Slaying the Philistines (Judges 15:14–19)

Thaw Collection, 2005

The present sheet is among the more than thirty studies Tintoretto and his workshop produced after a wax or clay replica of Michelangelo's 1528 sculptural model for Samson Slaying the Philistines. The spiraling and radically foreshortened figure of Samson wielding the jawbone of an ass atop one of his victims must have held a particular fascination for the artist, who rose to the challenge of producing a two-dimensional image of the sculpture with admirable skill.

In 1528 the republic of Florence commissioned Michelangelo to create a marble group representing Samson slaying the Philistines. The artist prepared a model but never executed the sculpture. Tintoretto owned a wax or clay model after Michelangelo's design, which is recorded in several drawings by him and members of his workshop. Tintoretto is said to have produced drawings after sculpture and "all good things" throughout his career, including statues by Jacopo Sansovino and casts of sculptures by Michelangelo and Giovanni Bologna.

Tintoretto's characteristic swelling contours and sharp flicks of the chalk heighten the drawing's sense of drama.

Innovations in Drawing

Technical and artistic innovations combined to make Renaissance Venice a vital creative center. Late-fifteenth-century artists generally worked in pen and ink and wash to make relatively finished drawings, but new techniques emerged that enabled them to produce more diverse, and often dramatic, effects. Artists such as Vittore Carpaccio perfected a method of applying ink with a brush onto Venetian blue paper (carta azzurra)—a support greatly prized by Albrecht Dürer. Artists of Titian and Bordone's generation, followed by Tintoretto, preferred a soft black chalk that was ideally suited to record tonal subtleties and create impressions of movement. Jacopo Bassano's innovative use of colored chalks made him a precursor to the pastel tradition. Tintoretto's younger contemporary, Veronese, developed entire compositions with rapid pen sketches while retaining a typically Venetian preoccupation with light.

Jacopo Bassano

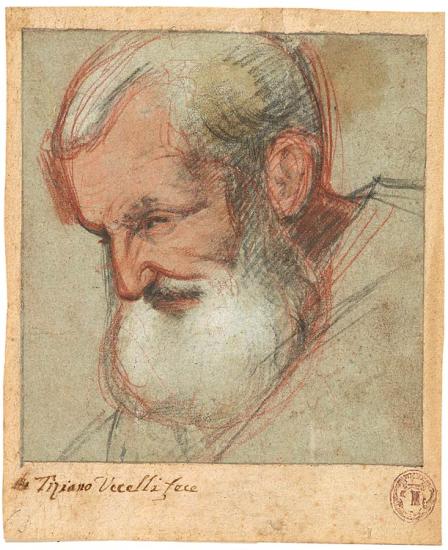

Head of an Old Man Turned to the Left

Gift of Lore Heinemann in memory of her husband, Dr. Rudolf J. Heinemann, 1998

Although Jacopo and his sons were based in his native Bassano del Grappa in the Veneto, the artist attracted numerous patrons from Venice for his vivid biblical scenes in rural settings.

This drawing is a study for the head of St. Joseph in Jacopo's painting The Flight into Egypt, now in the Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio. The painting is dated to the early 1540s on stylistic grounds. The drawing is one of the earliest examples of the artist's highly personal use of black, red, and white chalk on blue paper that was to become the hallmark of his style.

Innovations in Drawing

Technical and artistic innovations combined to make Renaissance Venice a vital creative center. Late-fifteenth-century artists generally worked in pen and ink and wash to make relatively finished drawings, but new techniques emerged that enabled them to produce more diverse, and often dramatic, effects. Artists such as Vittore Carpaccio perfected a method of applying ink with a brush onto Venetian blue paper (carta azzurra)—a support greatly prized by Albrecht Dürer. Artists of Titian and Bordone's generation, followed by Tintoretto, preferred a soft black chalk that was ideally suited to record tonal subtleties and create impressions of movement. Jacopo Bassano's innovative use of colored chalks made him a precursor to the pastel tradition. Tintoretto's younger contemporary, Veronese, developed entire compositions with rapid pen sketches while retaining a typically Venetian preoccupation with light.

Paolo Veronese

Studies for The Finding of Moses, ca. 1580

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909

In this lively sheet of studies for the Finding of Moses, circa 1580 (Prado, Madrid), the artist worked in rapid strokes of pen and brown ink to resolve problems not only of pose but of light and volume. The subject derives from the Old Testament account in which Moses was hidden by his mother in the bulrushes to escape Pharoah's order that all male Israelite infants be killed; he was later found and cared for by Pharoah's daughter.

Unlike Titian and Tintoretto—the other members of the triumvirate of extraordinary artists active in Venice during the second half of the sixteenth century—Veronese most commonly drew rough sketches with a fine pen, thin wash, and a light touch, combining several ideas for groups of figures on a single sheet.

The present drawing documents the artist's various ideas for his composition of the Finding of Moses, which he painted in several versions, all thought to date from the 1580s.

Innovations in Drawing

Technical and artistic innovations combined to make Renaissance Venice a vital creative center. Late-fifteenth-century artists generally worked in pen and ink and wash to make relatively finished drawings, but new techniques emerged that enabled them to produce more diverse, and often dramatic, effects. Artists such as Vittore Carpaccio perfected a method of applying ink with a brush onto Venetian blue paper (carta azzurra)—a support greatly prized by Albrecht Dürer. Artists of Titian and Bordone's generation, followed by Tintoretto, preferred a soft black chalk that was ideally suited to record tonal subtleties and create impressions of movement. Jacopo Bassano's innovative use of colored chalks made him a precursor to the pastel tradition. Tintoretto's younger contemporary, Veronese, developed entire compositions with rapid pen sketches while retaining a typically Venetian preoccupation with light.