Pierre-Jean Mariette and the Art of Collecting Drawings

Art dealer, collector, art historian, and connoisseur Pierre-Jean Mariette (1694–1774) was widely revered in his time for the breadth of his knowledge, particularly in the field of drawings. He believed that drawings—to a greater extent than paintings— revealed an artist’s true spirit and their careful study and analysis were therefore indispensable to an accurate history of art.

Mariette assembled one of the finest and most renowned drawings collections. Comprising over nine thousand sheets, the collection was dispersed at auction in 1775, and the drawings are now found all over the world. The selection shown here, drawn primarily from the Morgan’s holdings, speaks to Mariette’s discerning taste and erudition.

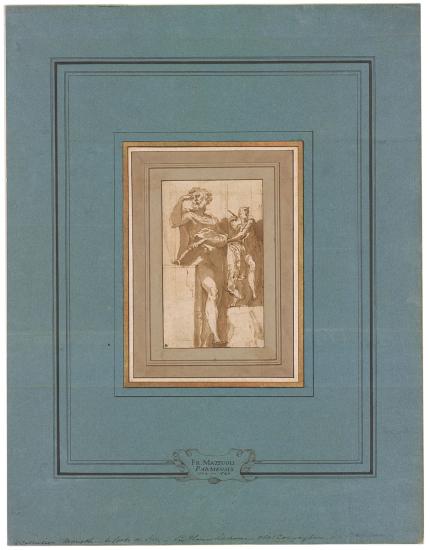

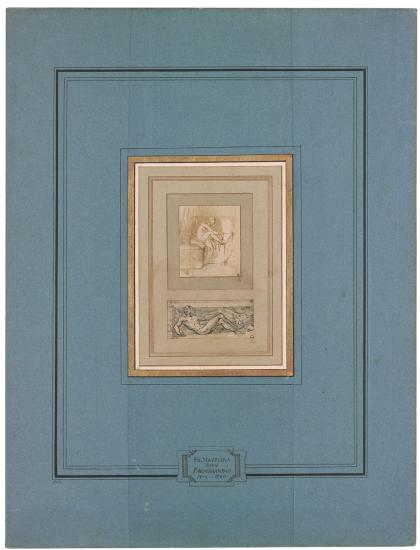

The characteristic blue mounts that Mariette devised for his drawings attest to the great care he took in displaying each sheet. While these mounts have always been celebrated for their elegance and refinement, museums often conceal them under neutral, modern mats. The works in this exhibition have been framed in accordance with Mariette’s original presentation.

Examination reveals that Mariette often restored drawings— even from fragments—to render appealing and clearly legible compositions. Although by today’s standards the practice of cutting, pasting, and retouching old master drawings is unorthodox, such interventions were an essential part of Mariette’s art of collecting.

This online exhibition was created in conjunction with the exhibition Pierre-Jean Mariette and the Art of Collecting Drawings, on view January 22 through May 1, 2016 and organized by Giada Damen, Moore Curatorial Fellow.

This exhibition builds on the recent research into Mariette as a collector undertaken by Pierre Rosenberg de l’Académie française and the Association Mariette, Paris; Kristel Smentek, Associate Professor of Art History, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge; and the Société Frits Lugt pour l’Étude des Marques de Collections, Fondation Custodia, Paris.

This exhibition is a program of the Drawing Institute at the Morgan Library & Museum. Additional support is provided by Lowell Libson, Ltd.

Exhibition Video

Exhibition Video

One of the most dramatic interventions performed by Mariette on drawings in his collection was the splitting of a single sheet of paper to separate the recto and the verso of double-sided drawings.

To gain a better understanding of how Mariette split his drawings, the Morgan’s Thaw Conservation Center attempted to separate a replica of an old master drawing with studies on both sides.

Overview

School of Albrecht Dürer

Stablemen of Various Nations, ca. 1517

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909

Mariette recognized the connection between this sheet and the celebrated series of woodcuts showing the Triumphal Procession of Emperor Maximilian I (1507–18). A monumental project executed by a group of artists in the emperor’s circle, the print series was left incomplete at the time of Maximilian’s death. In 1741 Mariette acquired a set of these extremely rare prints, which inspired him to write a study about their creation. He was convinced that Dürer was the author of the present sheet and responsible for the design of the print series. Scholars now believe that this drawing, depicting figures from the prints, was made by an artist in Dürer’s circle and that the monogram is not authentic.

Girolamo Mazzola Bedoli

The Annunciation, ca. 1546

Purchased on the Edwin Herzog Fund, 1999

Before entering Mariette’s collection, this drawing belonged to Pierre Crozat (1665–1740), a wealthy banker who was a close friend and fellow collector. In the catalogue of the Crozat sale, compiled by Mariette himself, the sheet was described as a “capital drawing” by the celebrated Mannerist Parmigianino. Only in the twentieth century have scholars recognized in this work the hand of Girolamo Mazzola Bedoli, a painter whose reputation had been forgotten in Mariette’s time but who was one of Parmigianino’s most talented successors in sixteenth-century Parma.

Not on view

Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola, called Parmigianino

Man Standing Beside a Plinth on Which He Rests a Book, and a Study of Saint Luke, ca. 1530–40

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909

Only a very small number of drawings in Mariette’s collection were displayed in frames. Most of the sheets in his cabinet were mounted on paper mats and stored inside cardboard portfolios. The organization of the drawings on independent mounts rather than in the bound albums more common at that time allowed for easy handling of the individual sheets.

Moreover, according to theories of visual perception at the time, a subject needed to be grasped by the viewer in a single glance (or coup d’oeil) in order to be fully apprehended. The generally standardized format of Mariette’s mats limited the dimensions of the sheets, allowing the viewer to see the whole composition at once.

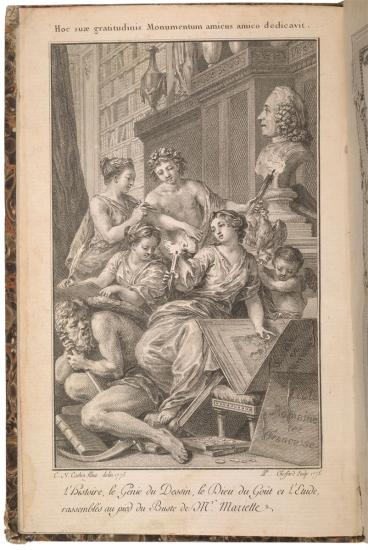

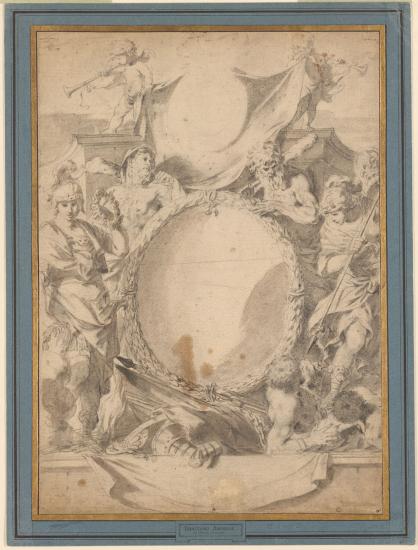

Pierre-François Basan

Catalogue raisonné des différens objets de curiosités dans les sciences et arts, qui composoient le cabinet de feu Mr Mariette, Paris, 1775

Between November 1775 and January 1776, Mariette’s art collection was sold by his heirs at auction in Paris. The collection was so significant that a comprehensive catalogue with a frontispiece designed by Charles-Nicolas Cochin (1715–1790) was printed. Mariette is represented in the frontispiece by a portrait bust surrounded by allegorical figures alluding to his accomplishments and erudition. The figure holding a flame and showing a portfolio of prints personifies Knowledge. Beside her, the woman poised with a chalk holder is an allegory of the Science of Drawing. A boy with a torch represents the God of Taste, and the putto with a rooster is a symbol of sleepless nights of study. History is illustrated as a woman writing in a book propped on Time’s shoulders.

Annibale Carracci

Annibale Carracci

(Italian, 1560–1609)

Study of a Tree, ca. 1600

Pen and brown ink, over black chalk

Private collection

In 1724, before he was able to acquire the sheet himself, Mariette made a copy of this drawing. At the auction of his collection, the copy and the original were offered for sale together. The catalogue explains that the copy, now in the Louvre, had been made by Mariette to deceive (faite à tromper). In Mariette’s erudite circle, the practice of copying drawings by old masters was considered a form of education. By trying to emulate the style of the artists of the past, amateur draftsmen and collectors could not only improve their drawing skills but also sharpen their ability to recognize different artists’ hands.

Salvator Rosa

Salvator Rosa (Italian, 1615–1673)

The Prodigal Son Kneeling Repentant Among Swine, ca. 1650

Pen and brown ink, brown wash

The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Rogers Fund, 1966

This drawing fetched one of the highest prices at the sale of Mariette’s collection, which attests to the passion of eighteenth-century collectors for the works of the Neapolitan artist. Mariette greatly admired Rosa’s drawings, particularly his landscapes, and was among the first in France to write about the painter and his art. The connoisseur described the artist’s inventive and often eccentric creations as the product of “the almost irrepressible ardor of a genius.”

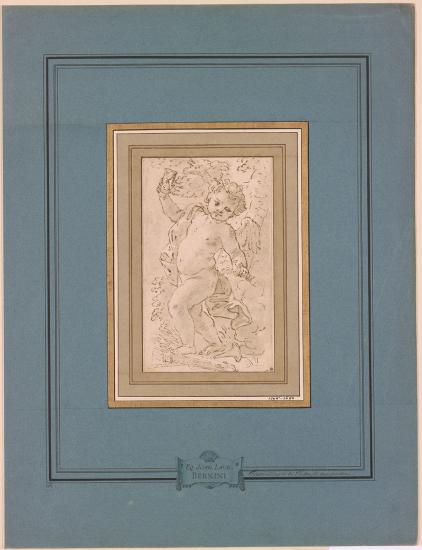

Giovanni Battista Gaulli, called Il Baciccio

Allegory of Love Tamed, 1690s

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909

As the name in the cartouche indicates, Mariette believed that this drawing was by the Italian sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680). Despite his incorrect attribution, Mariette was not too far off the mark: the drawing is by Gaulli, a pupil and close collaborator of Bernini’s in Rome. Gaulli was known to have executed fresco decorations based on Bernini’s inventions. Mariette described Gaulli as “the hand by which Bernini expressed in painting his new and clever ideas.” In this allegory of tamed love, Cupid tramples on his bow and arrows while holding an hourglass and a small dying bird, indicating that time and poverty are capable of extinguishing love.

Attributed to Johann Heinrich Roos

Attributed to Johann Heinrich Roos

(German, 1631–1685)

Study of a Cow, 1650–85

Black chalk, heightened with white

Attributed to Pieter Jacobsz. van Laer

(Dutch, ca. 1592/95–ca. 1642)

Study of a Donkey, 1620–40

Black chalk, pen and brown ink, gray wash

The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Rogers Fund, 1964

Mariette did not share his contemporaries’ taste for Northern drawings and, at times, criticized his fellow collectors’ purchases of expensive sheets representing “drunken people, cowherds, [and] trees.” Yet he aimed to make the scope of his collection encyclopedic, and so, along with his favorite Italian and French drawings, he also acquired sheets by Northern artists. Here he arranged on the same mat two animal studies attributed to a German and a Dutch artist. Mounting the two drawings together was a way to encourage comparisons between the masters’ styles.

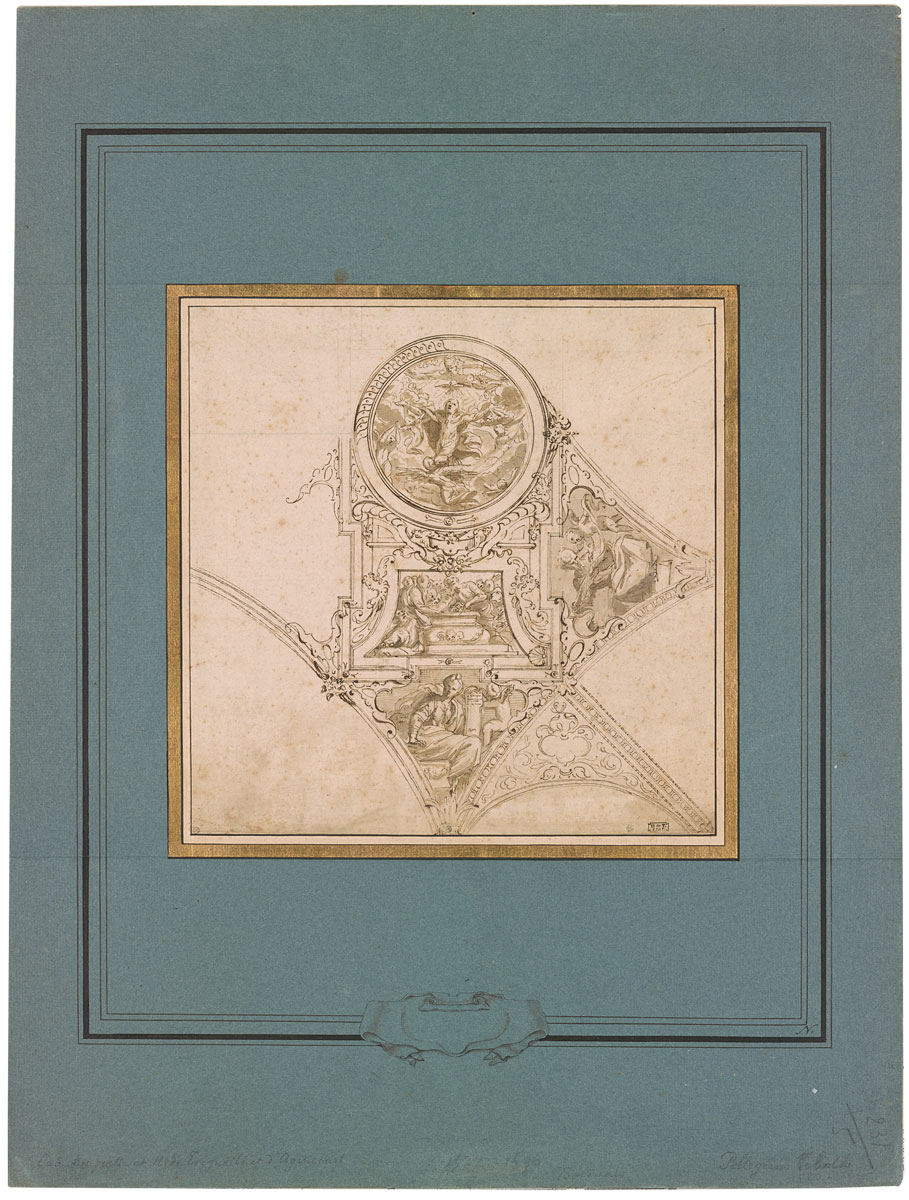

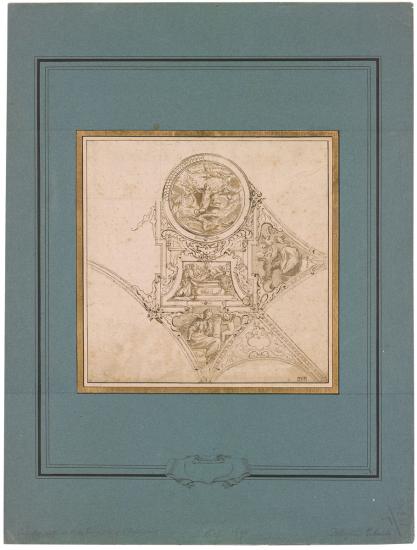

Giovanni Baglione

Ceiling Design with the Assumption of the Virgin, a Prophet, and a Sibyl, ca. 1598

Purchased as the gift of the Fellows

In rare instances, Mariette did not inscribe an artist’s name in the cartouche on the mount, most likely because he was unsure about the drawing’s correct author. In a 1765 letter to Mariette, Giovanni Bottari—a fellow connoisseur—reassured him: “It is almost as those who write about art are struck by a curse, as everyone has made and keeps making incredible mistakes every day. And this is true also for me as I made mistakes on things I knew as well as my own name.”

Attributed to Cristofano Allori

Lady Seated with Two Children, ca. 1600–20

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909

Mariette meticulously mounted his drawings on custom-made blue paper mats embellished with cartouches bearing the name of the artist, gold filets, and decorative borders. His mats provide a refined way of displaying and storing drawings. At the same time, they deeply influence the viewer’s perception of the sheets. The contrast between the dark mat and the light paper of the drawing forces the eye to focus on the image at the center. This visual effect becomes particularly clear when comparing a drawing with Mariette’s original mat to one without it.

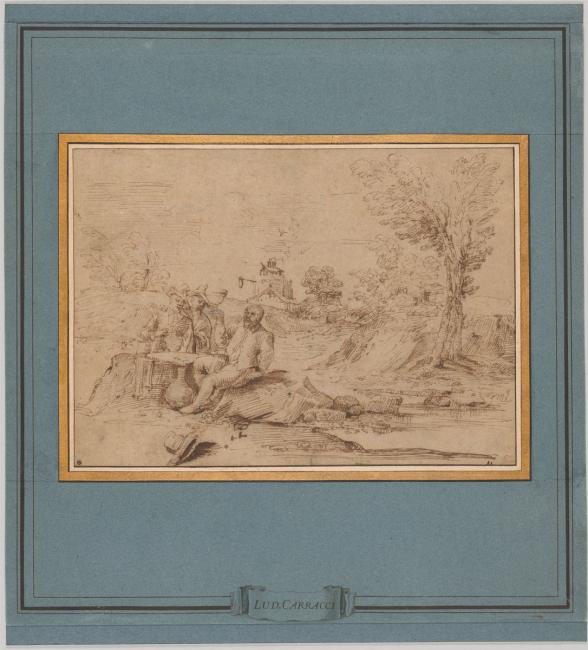

Francesco Brizio

Francesco Brizio

(Italian, ca. 1574–1623)

Wooded River Landscape with Three Peasants Drinking, 1610s

Pen and brown ink, over black chalk

Private collection

For his characteristic mounts, Mariette used paper of a distinctive hue derived from indigo, which gave rise to the description of the color as “Mariette blue.” The collector employed made-to- order paper that came in slightly different shades of blue but later turned to an evenly colored and less expensive variety available in larger quantities. Mariette’s collection was particularly rich in sixteenth-century Bolognese drawings, among which was this landscape attributed to Ludovico Carracci (1555–1619). The drawing is in fact a work of the painter and engraver Brizio, one of Ludovico’s pupils who closely followed his master’s drawing style.

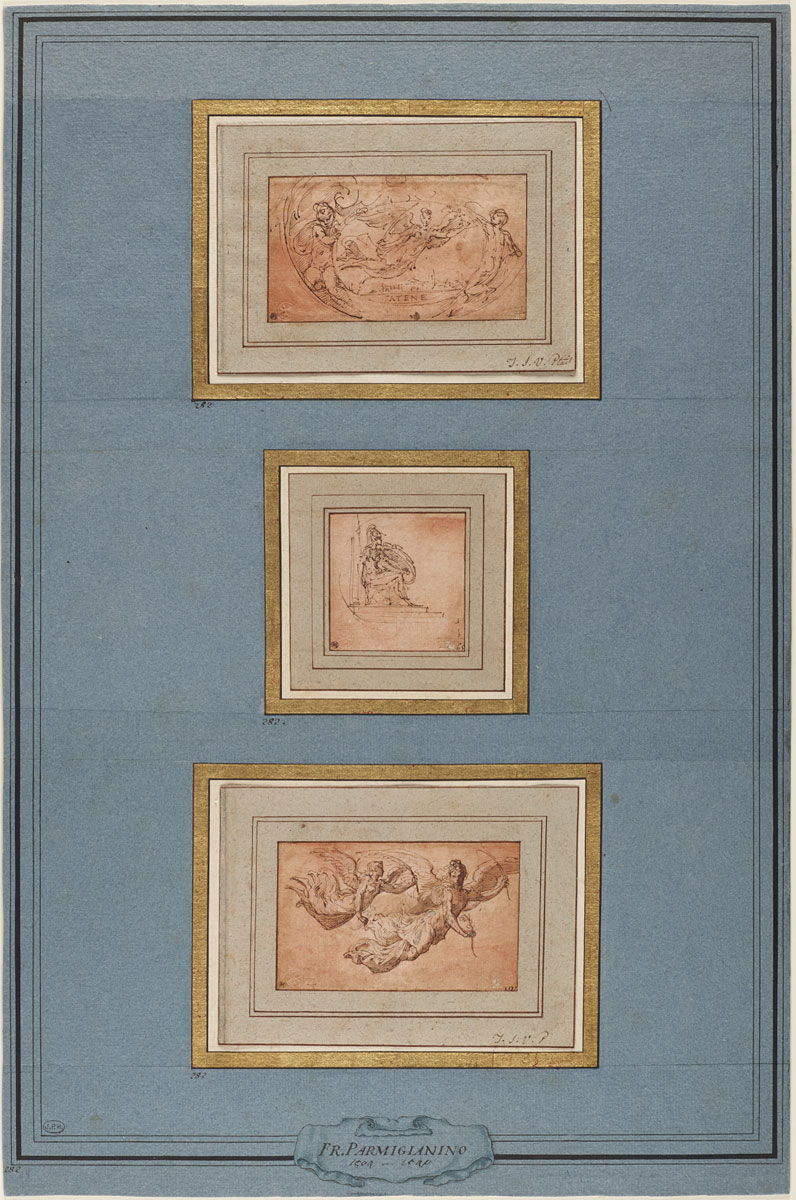

Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola, called Parmigianino

Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola, called Parmigianino

(Italian, 1503–1540)

Study for Figure of Victory on Pectoral Brooch of Pallas Athena, ca. 1531–35

Pen and brown ink, on tan paper prepared with salmon wash

Seated Figure of Pallas Athena, ca. 1531–35

Pen and brown ink, on tan paper prepared with salmon wash

Two Studies for Figure of Victory, ca. 1531–35

Pen and brown ink, brown wash, heightened with lead white

Princeton University Art Museum; Gift of Peter W. Josten in memory of Stephen Spector, 1989

Mariette owned over fifty drawings by Parmigianino, including many small sketches like the three displayed here— two are related to the artist’s painting of Pallas Athena. In this case, the collector’s elegant blue mat was constructed to frame the three fragments together. Particular attention was also paid to the fact that the upper and lower drawings bear pen-and-ink studies on the versos. They are attached to the mat along a single edge; Mariette added abbreviated inscriptions to encourage the viewer to turn the paper over and admire the versos: T. S. V. P. (Tournez S’il Vous Plait, “Please Turn Over”).

Annibale Carracci

Annibale Carracci

(Italian, 1560–1609)

Study for Choice of Hercules, ca. 1595–97

Pen and brown ink, over red chalk

Princeton University Art Museum; Museum purchase, Fowler McCormick, Class of 1921, Fund, 2008

Mariette was among the earliest collectors to highlight the provenance of the drawings he acquired. Occasionally, as in the cartouche on this mount, he added to the artist’s name those of previous notable owners of the drawing. Here he proudly listed his name in Latin with those of the French painter Pierre Mignard (1612–1695) and the Parisian financier Pierre Crozat (1665–1740), both of whom had owned this important study. The sketch is a compositional idea for Carracci’s painting Choice of Hercules originally in the Farnese Palace in Rome.

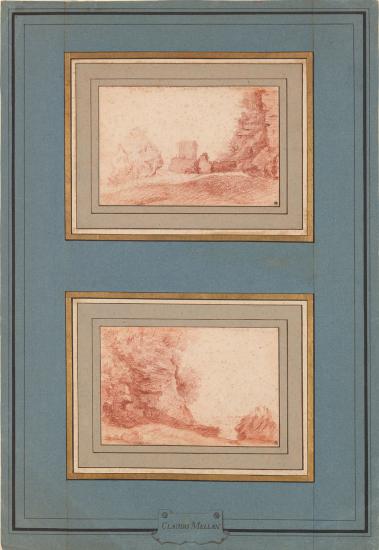

Claude Mellan

Landscape with a Small Temple, ca. 1624–36

Rocky Landscape, ca. 1624–36

Purchased on the Baker Fund, 1985

Mariette aimed to mount the drawings in his collection on uniform mats of standard dimensions—usually around 20 x 15 inches (510 x 380 mm). Having the drawings similarly matted gave aesthetic unity to the collection and facilitated the organization of the sheets in portfolios. He often combined several small studies by a single artist on the same mat, as with these two rare chalk landscapes by Claude Mellan, an artist best known as an engraver and portraitist.

Sébastien Bourdon

Allegorical Composition in Honor of Christina, Queen of Sweden, 1640s

Purchased as the gift of the Fellows, 1961

Although Mariette preferred mats of uniform size for his drawings, the standard format of the mounts was sometimes altered to accommodate larger compositions, such as this sheet. Occasionally he rejected drawings too large to fit properly in his window mats. Unique in Bourdon’s oeuvre, this sheet is the initial design for the border of a printed portrait of Queen Christina of Sweden engraved in 1656 by Michel Lasne (1590–1667).

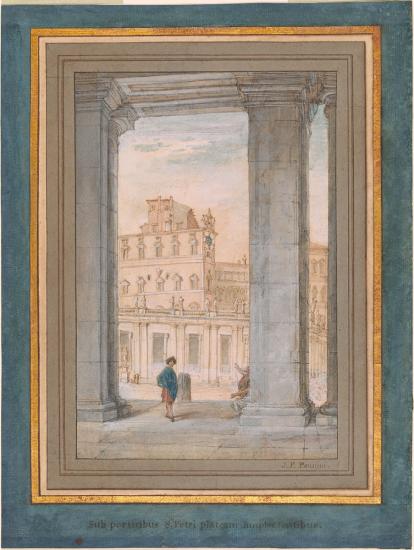

Giovanni Paolo Panini

View of the Vatican Palace from the Colonnade of St. Peter’s, ca. 1759–62

Thaw Collection

Mariette sometimes added handwritten captions on the mounts of drawings. He believed, as did other collectors, that understanding the subject of a composition was crucial to enjoying and appreciating a drawing fully. The Latin inscription, which translates “Waiting under the colonnades of Saint Peter’s Square,” clarifies the location of this scene. Mariette collected works by contemporary artists as well as drawings by old masters. He owned over thirty drawings by Panini, who was a member of the French Academy in Rome and who influenced a generation of French draftsmen.

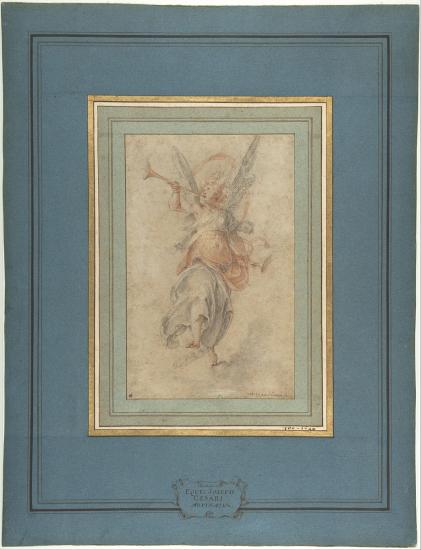

Giuseppe Cesari, called Cavalier d’Arpino

Giuseppe Cesari, called Cavalier d’Arpino (Italian, 1568–1640)

Allegorical Figure of Fame, ca. 1590

Graphite and red chalk, heightened with white gouache

The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Gift of Mrs. Alfred H. Barr, Jr., 1986

Behind their simple appearance, Mariette’s mounts conceal elaborate constructions. Each mat consists of a series of at least four or five overlapping sheets of paper. The bottom layer is typically made of thin cream cardboard, on top of which are laid one or two intermediary sheets that generally consist of recycled engravings. The drawing is glued onto these sheets with a border of reserved paper left around it. The topmost layer consists of strips of blue paper framing the drawing. Mariette carefully studied the presentation of each sheet, and his mats have many subtle variations.

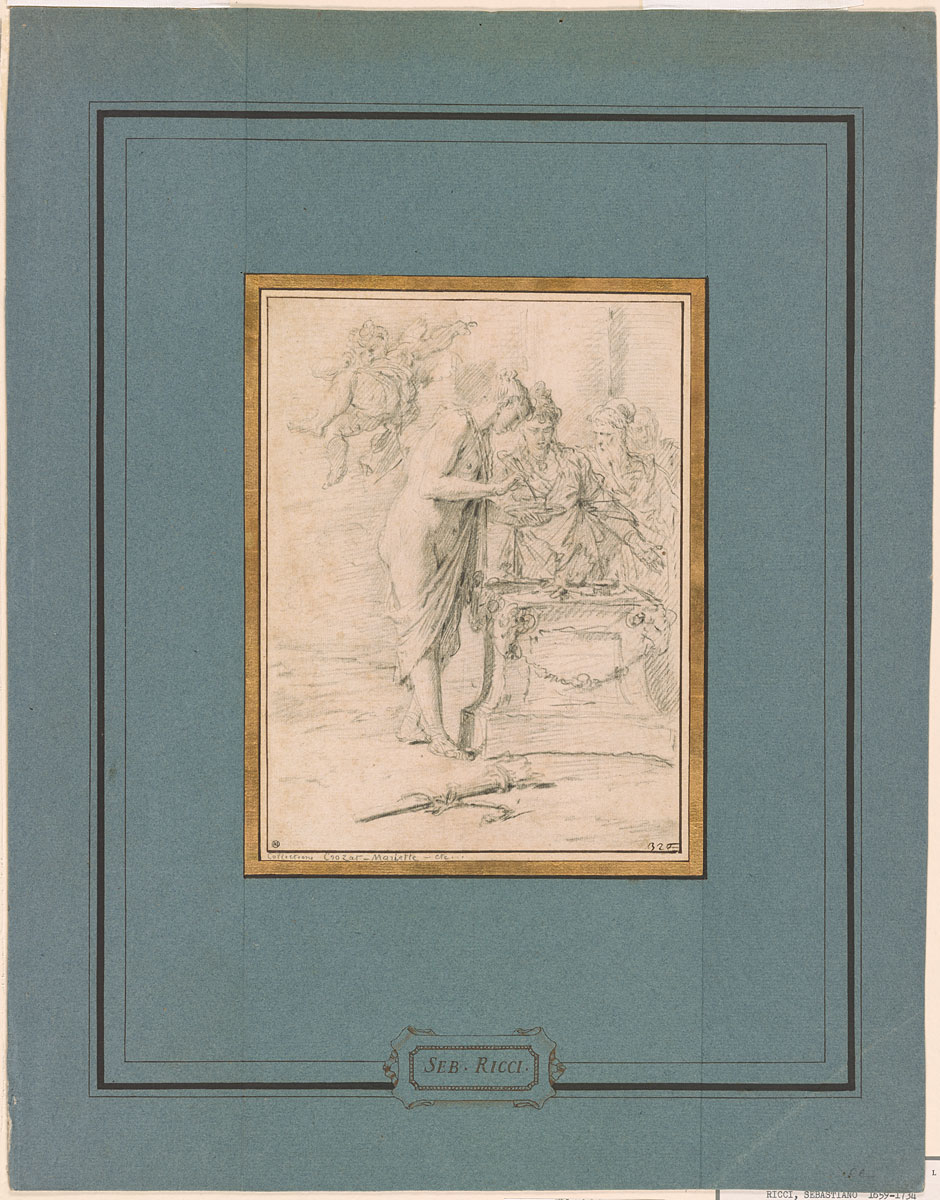

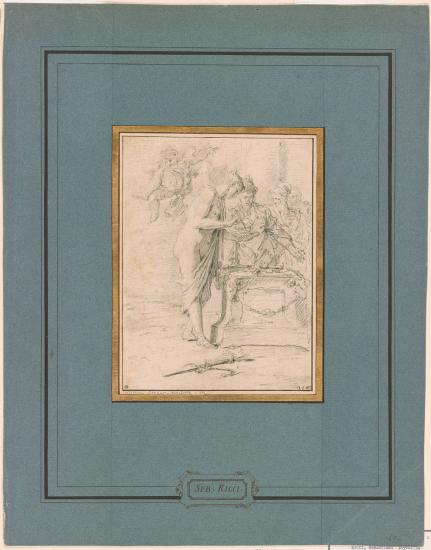

Sebastiano Ricci

Venus and Cupid with Other Figures Before an Altar, ca. 1700

Purchase, 1950

Drawings often show the signs of their collecting history, revealing how they were manipulated or modified by earlier owners. Past—and present—collectors have often chosen to mark their sheets with a stamp or numbers. Mariette had his own personal device, visible in the lower left corner of this drawing. His mark consists of a stamp, applied in black ink, with the collector’s Latin initials— P(etrus) I(oannes) M(ariette)—interlaced in a circle. This study also bears, at the lower right, a handwritten number indicating it came from the collection of Pierre Crozat (1665–1740).

Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola, called Parmigianino

Nude Woman Seated on a Bed, ca. 1525–30

Pen and brown ink, brown wash

Reclining Male Nude with Legs Crossed, ca. 1533–39

Pen and black ink, gray wash

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909

Mariette was an expert paper restorer and often manipulated the drawings in his collection with the intention of improving their legibility. He commonly added strips of paper around the edges of drawings not only to supply missing parts of the composition but also to center the sheets on the mounts more precisely. On this mat he framed two very small Parmigianino sketches together. Close observation shows that the tiny fragment at the top was enlarged around the edges and its composition completed by the collector in pen and ink.

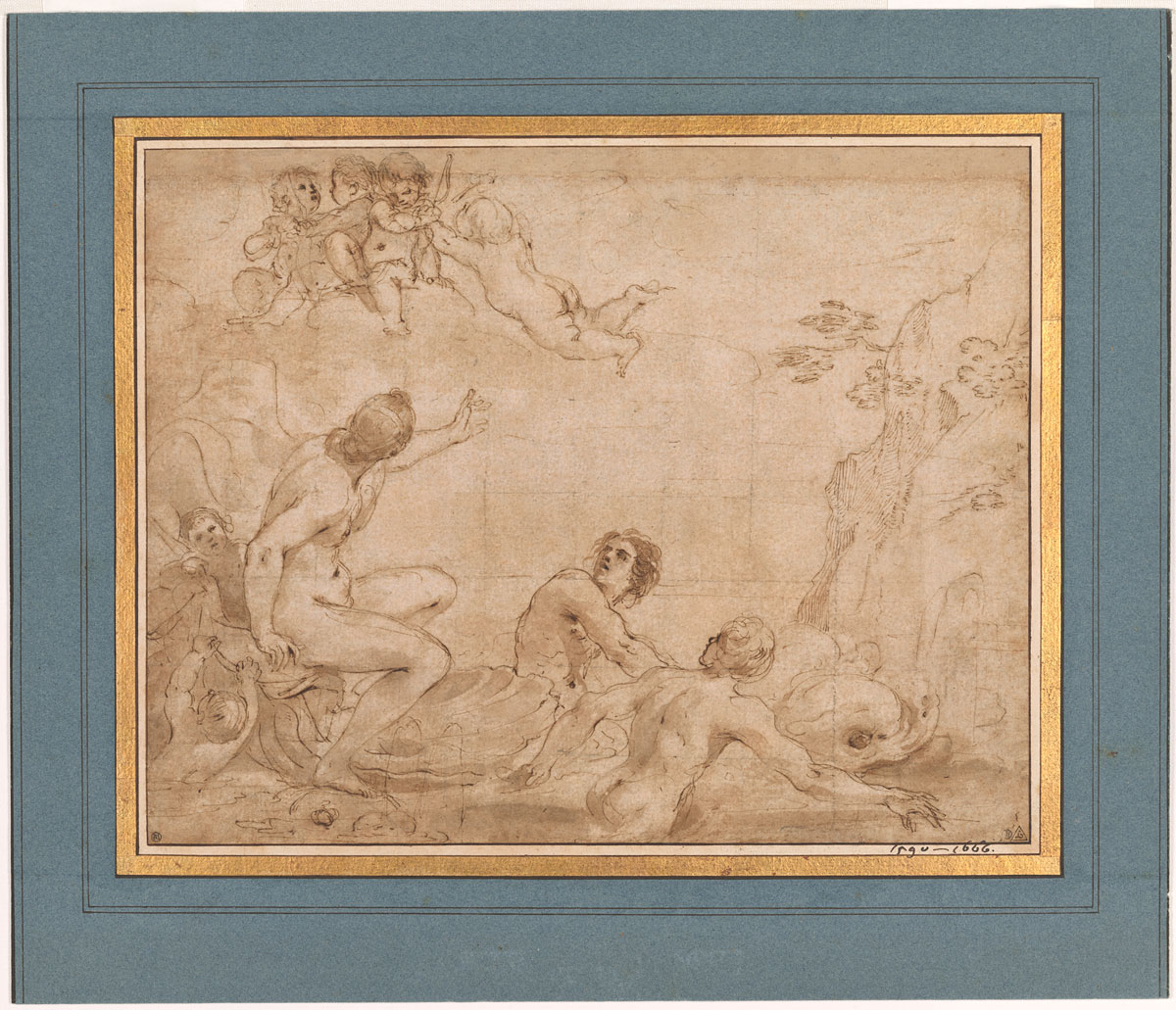

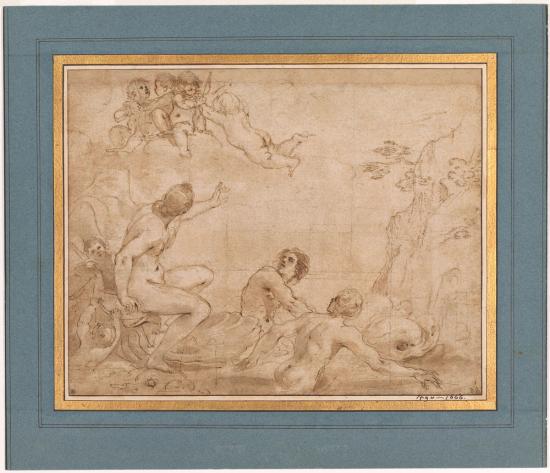

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, called Guercino

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, called Guercino

(Italian, 1591–1666)

The Triumph of Galatea, 1620s

Pen and brown ink, brown wash, squared in black chalk

Private collection

In Mariette’s time, enhancing the appearance of a fragmentary drawing was considered helpful to the viewer rather than detrimental to the authenticity of a sheet. As with fragments of antique sculptures, master drawings were restored to evoke their original appearance. Mariette was extremely skilled in these restorations, and his additions are often difficult to discern. Only the aging of the glue makes them visible today. Along the upper edge of this sheet, the collector added a horizontal strip of paper upon which he sketched the missing portion of the heads of the three flying putti.

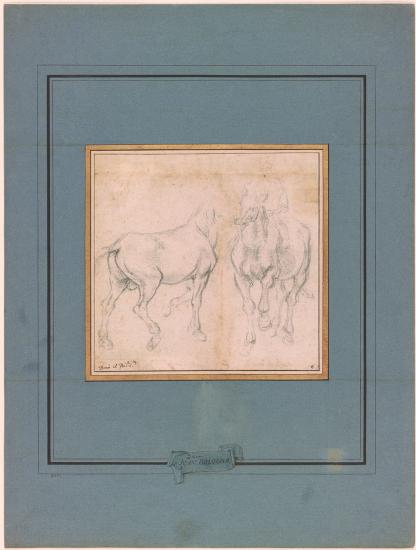

Florentine school, sixteenth century

Two Studies of a Horse, after 1550

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909

These two studies of horses, which Mariette believed to be by the sculptor Giambologna (1529–1608), today seem to be one composition, but this was not originally the case. Upon careful examination, a vertical seam is visible between the two animals. The sketches were probably drawn by the artist on a larger sheet of paper, perhaps too wide to fit in Mariette’s standard mat. The collector cut out the two studies and carefully reassembled them closer together to create a more compact composition. Similarly, he removed the old handwritten inscription from the original sheet and inserted it at the lower left of the newly reconfigured drawing.

Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola, called Parmigianino

Girl Seated on the Ground Near a Chair, ca. 1524

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909

Mariette and his contemporaries believed that a work of art needed to be easily apprehended in order to be correctly analyzed and understood. Damages and lacunae were considered obstacles to the viewer’s ability to observe and learn. It was therefore important to enhance the legibility of some sheets. This drawing by Parmigianino was only a fragment, but Mariette extended it at top and bottom. He completed the chair and the girl’s gown but also added the detail of the window.

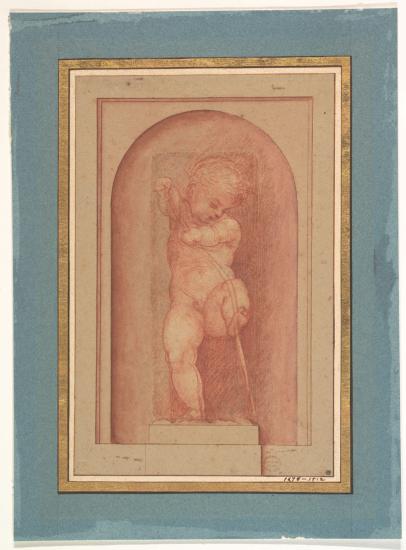

Attributed to Giorgione

Attributed to Giorgione

(Italian, 1477/78–1510)

Putto Bending a Bow, ca. 1505–8

Red chalk

The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Rogers Fund, 1911

Mariette extended this sixteenth-century drawing of a putto by adding the niche and pedestal upon which it stands. He based these additions on historical research and believed that the drawing was related to Giorgione’s fresco decoration of the facade of the Fondaco dei Tedeschi, the headquarters of the German merchants in Venice. In Mariette’s time, the frescoes were almost completely deteriorated, yet written accounts described the many different motifs painted by Giorgione on the facade. Among these was the figure of an angel in the guise of Cupid.

Video: Pierre-Jean Mariette and Splitting Drawings

One of the most dramatic interventions performed by Mariette on drawings in his collection was the splitting of a single sheet of paper to separate the recto and the verso of double-sided drawings.

Mariette’s contemporaries were amazed by his skill in this challenging operation. In 1761, the comte de Caylus wrote:

Mariette [is] the most skillful and patient man alive. I will give you an example. He has more than once split [a sheet] of paper and placed on the same surface two drawings which the author had made on the recto and verso of the same sheet and those drawings were by Raphael!

To gain a better understanding of how Mariette split his drawings, the Morgan’s Thaw Conservation Center attempted to separate a replica of an old master drawing with studies on both sides.

The experiment is shown in this video.

This video draws upon the recent research into Mariette as a collector undertaken by Pierre Rosenberg de l’Académie française and the Association Mariette, Paris; Kristel Smentek, Associate Professor of Art History, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge; and the Société Frits Lugt pour l’Étude des Marques de Collections, Fondation Custodia, Paris.

Support for this video was provided by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Program in Library and Archive Conservation Education.