The Fashion Revolution Begins

Instructions for Kings, in French

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1911

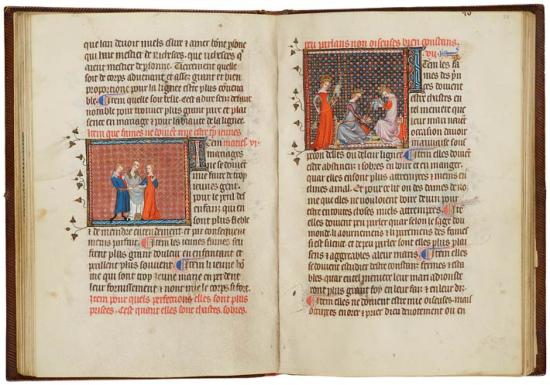

The blue surcot worn by the groom in the left miniature is shorter than before. While his skirt is still full, the bodice of his surcot is now tighter, made possible by the invention of the set-in sleeve. His blue sleeves terminate at the elbow in decorative extensions, revealing the red sleeves of his kirtle. His chaperon rests on his shoulders. The bride and the three princesses in the right miniature all wear the open-sided surcot over kirtles with tight sleeves. Low, horizontal necklines reveal their bare necks and the tops of their shoulders.

Fashion Revolution

The "Fashion Revolution" began around 1330 with the invention of the set-in sleeve. Earlier garments were T-shaped, with sleeves of a piece with the body or sewn on a flat seam. The new technique (still in use today) cut sleeves with rounded tops and gathered them along basted threads into armholes in the bodice. This new tailoring, combined with the use of multiple buttons, made possible a snugly fitted bodice and tight sleeves. While providing more freedom of movement, the new garment for men—the cote hardy—also revealed the shapes of the wearer's torso and arms. The "Fashion Revolution" gave birth to men's modern dress, creating an outfit that was sharply differentiated from the dress of women.

Women's fashions, however, were also affected. Tighter bodices and sleeves became popular, as did exposed necks and shoulders. The sides of the outer garment, the surcot, now sometimes featured seductively large, peek-a-boo openings.

Men—and some women—turned the chaperon (a hood with an attached cape and tail) into a fashion accessory that lasted over a hundred years.

The Fashion Revolution Explodes

Jacques de Longuyon, Vows of the Peacock, in French

Gift of the Trustees of the William S. Glazier Collection, 1984

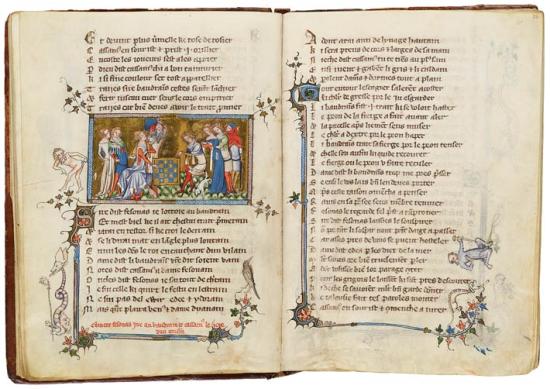

The four young men in this miniature are all dressed at the height of the new fashion. They wear the new short garment, the cote hardy: buttoned down the front, it is tight at the skirt, bodice, and sleeves. All sport chaperons, two of which are dagged (cut into decorative strips). Some wear delicate shoes, while the youth in blue wears chaussembles: hose with leather soles. The two women at the left wear the open surcot. The woman in blue wears the closed surcot, furnished with a lined slit for access to the kirtle. She also wears tippets: thin decorative bands of cloth falling from the elbow.

Fashion Revolution

The "Fashion Revolution" began around 1330 with the invention of the set-in sleeve. Earlier garments were T-shaped, with sleeves of a piece with the body or sewn on a flat seam. The new technique (still in use today) cut sleeves with rounded tops and gathered them along basted threads into armholes in the bodice. This new tailoring, combined with the use of multiple buttons, made possible a snugly fitted bodice and tight sleeves. While providing more freedom of movement, the new garment for men—the cote hardy—also revealed the shapes of the wearer's torso and arms. The "Fashion Revolution" gave birth to men's modern dress, creating an outfit that was sharply differentiated from the dress of women.

Women's fashions, however, were also affected. Tighter bodices and sleeves became popular, as did exposed necks and shoulders. The sides of the outer garment, the surcot, now sometimes featured seductively large, peek-a-boo openings.

Men—and some women—turned the chaperon (a hood with an attached cape and tail) into a fashion accessory that lasted over a hundred years.

Idleness Personified

Pilgrimage of Human Life, in French and Latin

Purchased, 1931

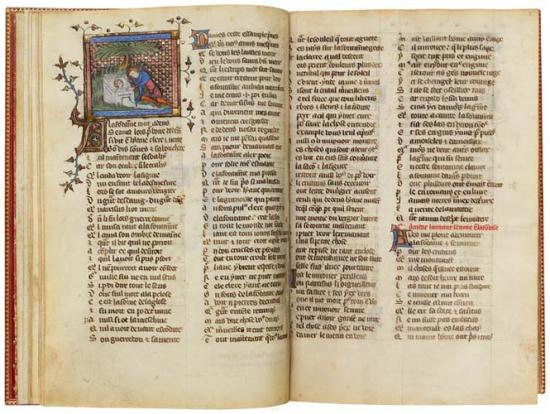

In this allegorical treatise, Idleness is personified as a lazy but beautifully dressed and perfectly coiffed young woman. The tight bodice of her surcot cinches her high, narrow waist, emphasizing the curves of her bosom and belly. Slender tippets fall from her elbows, and the pointed tips of her narrow shoes poke from beneath her hem. A low neckline exposes her neck and the tops of her shoulders, while braided hair frames her face. She gestures condescendingly toward the humble pilgrim, dressed like a monk and equipped with a walking stick and satchel of provisions.

Fashion Revolution

The "Fashion Revolution" began around 1330 with the invention of the set-in sleeve. Earlier garments were T-shaped, with sleeves of a piece with the body or sewn on a flat seam. The new technique (still in use today) cut sleeves with rounded tops and gathered them along basted threads into armholes in the bodice. This new tailoring, combined with the use of multiple buttons, made possible a snugly fitted bodice and tight sleeves. While providing more freedom of movement, the new garment for men—the cote hardy—also revealed the shapes of the wearer's torso and arms. The "Fashion Revolution" gave birth to men's modern dress, creating an outfit that was sharply differentiated from the dress of women.

Women's fashions, however, were also affected. Tighter bodices and sleeves became popular, as did exposed necks and shoulders. The sides of the outer garment, the surcot, now sometimes featured seductively large, peek-a-boo openings.

Men—and some women—turned the chaperon (a hood with an attached cape and tail) into a fashion accessory that lasted over a hundred years.

Narcissus Admires Himself

Romance of the Rose, in French

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1904

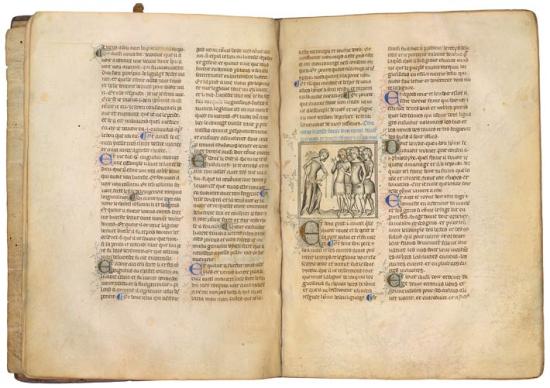

Narcissus admires his handsome reflection in a fountain. His hair is fashionably wavy and features a dorlott: a curl or bang centered above the forehead. His cote hardy is tight on the bodice with a loose, gored skirt with a dagged hem. A purse, called a gipser, dangles from his thin belt. His blue chaperon, embroidered with a decorative hem, hangs foppishly loose around his shoulders. He wears orange hose and elegant shoes with open frets.

Fashion Revolution

The "Fashion Revolution" began around 1330 with the invention of the set-in sleeve. Earlier garments were T-shaped, with sleeves of a piece with the body or sewn on a flat seam. The new technique (still in use today) cut sleeves with rounded tops and gathered them along basted threads into armholes in the bodice. This new tailoring, combined with the use of multiple buttons, made possible a snugly fitted bodice and tight sleeves. While providing more freedom of movement, the new garment for men—the cote hardy—also revealed the shapes of the wearer's torso and arms. The "Fashion Revolution" gave birth to men's modern dress, creating an outfit that was sharply differentiated from the dress of women.

Women's fashions, however, were also affected. Tighter bodices and sleeves became popular, as did exposed necks and shoulders. The sides of the outer garment, the surcot, now sometimes featured seductively large, peek-a-boo openings.

Men—and some women—turned the chaperon (a hood with an attached cape and tail) into a fashion accessory that lasted over a hundred years.

A Well-Dressed Lucretia Commits Suicide

The Game of Chess Moralized, in French

Gift of the Trustees of the William S. Glazier Collection, 1984

Lucretia's surcot has a fashionably tight bodice and sleeves, from the elbows of which hang slender tippets. The neckline is curved, rising in front but falling off the shoulders. The braids of her hair have been folded along the slanted posts of a tressour, framing her face. Her father, husband, and friends are all dressed in tight cotes hardy with dagged hems. Lucretia's father also wears tippets from his sleeves and a dagged chaperon. The men sport wavy hair with a dorlott: a curl or bang above the forehead.

Fashion Revolution

The "Fashion Revolution" began around 1330 with the invention of the set-in sleeve. Earlier garments were T-shaped, with sleeves of a piece with the body or sewn on a flat seam. The new technique (still in use today) cut sleeves with rounded tops and gathered them along basted threads into armholes in the bodice. This new tailoring, combined with the use of multiple buttons, made possible a snugly fitted bodice and tight sleeves. While providing more freedom of movement, the new garment for men—the cote hardy—also revealed the shapes of the wearer's torso and arms. The "Fashion Revolution" gave birth to men's modern dress, creating an outfit that was sharply differentiated from the dress of women.

Women's fashions, however, were also affected. Tighter bodices and sleeves became popular, as did exposed necks and shoulders. The sides of the outer garment, the surcot, now sometimes featured seductively large, peek-a-boo openings.

Men—and some women—turned the chaperon (a hood with an attached cape and tail) into a fashion accessory that lasted over a hundred years.