The Bookman

When he was a boy growing up in New England, J. Pierpont Morgan began collecting autographs of famous men— a popular pastime of the day. Before he turned fifty, he commissioned a catalogue of his growing personal library, which now encompassed much more than autographs. But it was only after he turned sixty that he started making purchases on a prodigious scale. By the time of his death in 1913 at age seventy-five, he was one of the world’s elite collectors of rare books and manuscripts.

What allowed Morgan to create such a magnificent library? He benefited from economic privilege and astute family guidance. As a young man, he studied in Switzerland and Germany before returning to New York to embark upon his financial career. His father and nephew, both named Junius and both committed bibliophiles, introduced him to the practice of acquiring books as treasured objects more so than as texts for reading. Thus equipped, Morgan amassed the collection that would fill his “bookman’s paradise.”

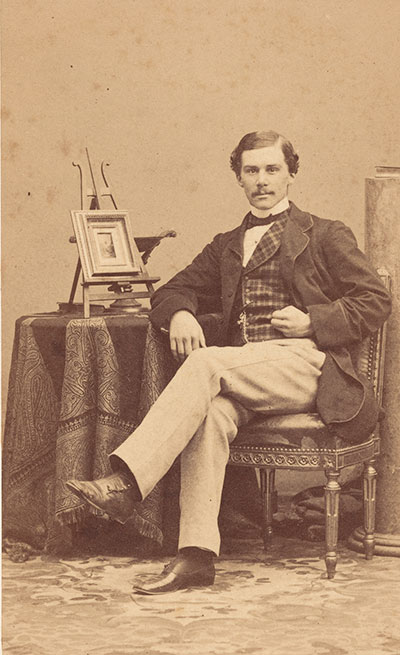

J. Pierpont Morgan, ca. 1860s. Photo: Disdéri & Co., Paris.

The Young Reader

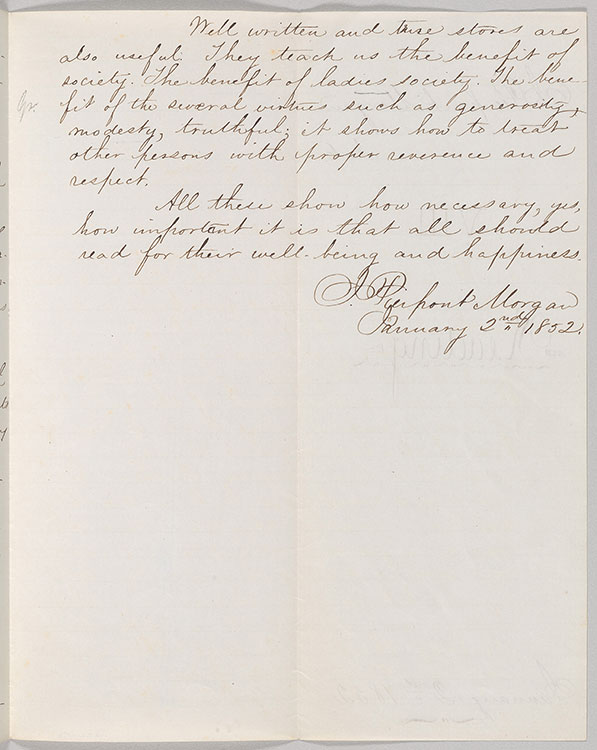

As a fourteen-year-old student at Boston’s English High School, the future bibliophile composed this essay on the value of reading. In impeccable cursive, young Morgan (known as Pierpont to family and friends) pronounced most novels “useless trash” but allowed that “well written and true stories” can teach us “how to treat other persons with proper reverence and respect.” He concluded, “How necessary, yes, how important it is that all should read for their well-being and happiness.”

J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913)

“Reading”

High school essay with instructor’s notes in pencil, 2 January 1852

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1196

"Reading", p. 2

As a fourteen-year-old student at Boston’s English High School, the future bibliophile composed this essay on the value of reading. In impeccable cursive, young Morgan (known as Pierpont to family and friends) pronounced most novels “useless trash” but allowed that “well written and true stories” can teach us “how to treat other persons with proper reverence and respect.” He concluded, “How necessary, yes, how important it is that all should read for their well-being and happiness.”

J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913)

“Reading”

High school essay with instructor’s notes in pencil, 2 January 1852

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1196

"Reading", p. 3

As a fourteen-year-old student at Boston’s English High School, the future bibliophile composed this essay on the value of reading. In impeccable cursive, young Morgan (known as Pierpont to family and friends) pronounced most novels “useless trash” but allowed that “well written and true stories” can teach us “how to treat other persons with proper reverence and respect.” He concluded, “How necessary, yes, how important it is that all should read for their well-being and happiness.”

J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913)

“Reading”

High school essay with instructor’s notes in pencil, 2 January 1852

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1196

"Reading", p. 4

As a fourteen-year-old student at Boston’s English High School, the future bibliophile composed this essay on the value of reading. In impeccable cursive, young Morgan (known as Pierpont to family and friends) pronounced most novels “useless trash” but allowed that “well written and true stories” can teach us “how to treat other persons with proper reverence and respect.” He concluded, “How necessary, yes, how important it is that all should read for their well-being and happiness.”

J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913)

“Reading”

High school essay with instructor’s notes in pencil, 2 January 1852

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1196

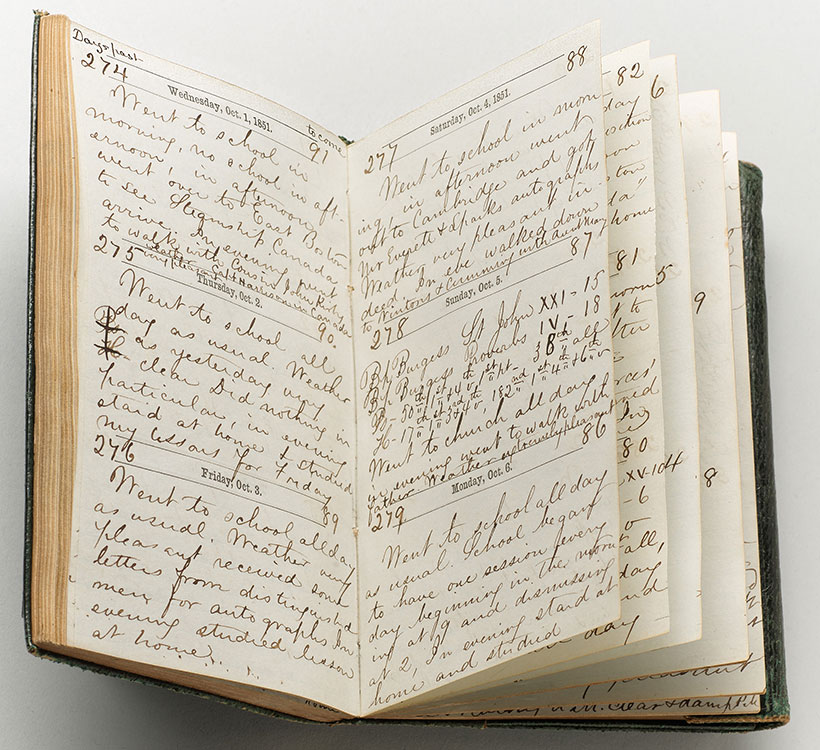

Autograph Collecting

Fourteen-year-old Morgan received this pocket diary as a Christmas gift from his father. In it, the young Morgan faithfully recorded his daily activities, including his early efforts to build an autograph collection. On 3 October 1851, he noted that he had “received some letters from distinguished men.” The next day, he secured the autographs of two of his grandfather’s acquaintances: Jared Sparks, president of Harvard College, and Edward Everett, a prominent educator and politician.

J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913)

Diary, 1851

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1196

A Library Without Books

During the 1880s, the Manhattan home of J. Pierpont Morgan and his second wife, Frances (Fanny), was featured in a lavish volume depicting the domestic interiors of wealthy Americans. This photograph shows their home library, which was luxuriously outfitted by decorator Christian Herter and illuminated with Thomas Edison’s new electric lighting. But the library is curiously short on books. Only a sliver of low shelving is visible to the right of the windows. In the freestanding library Morgan would commission two decades later, fine volumes would be very much in evidence.

The house pictured here, later demolished, was located at the corner of 36th Street and Madison Avenue, on the site of the building you are in now.

“Mr. J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library”

Modern reproduction of a photograph published in Artistic Houses: Being a Series of Interior Views of a Number of the Most Beautiful and Celebrated Homes in the United States; With a Description of the Art Treasures Contained Therein, vol. 1

New York: D. Appleton, 1883

The Morgan Library & Museum; PML 127667

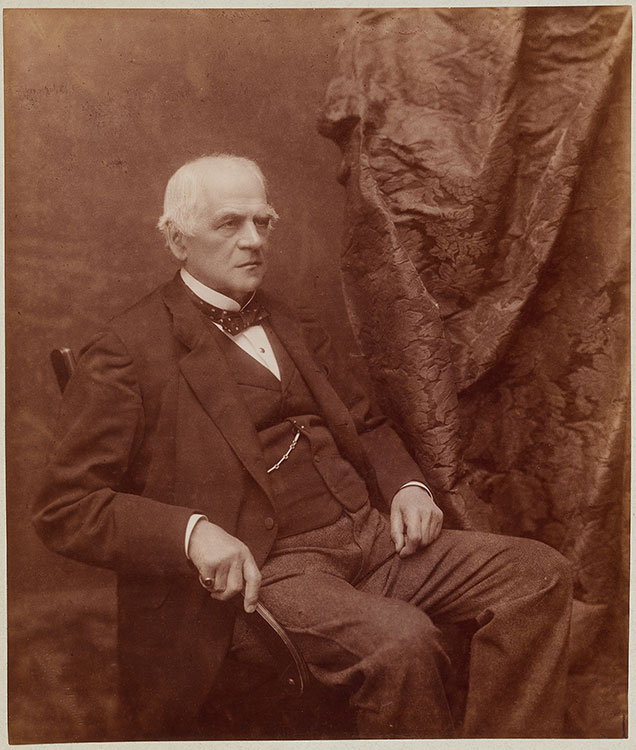

Morgan's Father: Banker and Bookman

Head of a successful London-based merchant-banking firm, Junius Spencer Morgan (1813–1890) took a strong hand in directing his son Pierpont’s early career on Wall Street. Junius was also an avid collector of books and manuscripts. When Junius died of injuries sustained in a carriage accident in 1890, Pierpont inherited $15 million (equivalent to about $463 million today) and found himself well positioned to build his business, as well as to devote increasingly large sums to the acquisition of rare books and artworks.

H. S. Mendelssohn, London

Junius Spencer Morgan, undated (before 1890)

Albumen print

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 3286

J. Pierpont Morgan, Rising Bibliophile

By the 1880s—about the time of this portrait—Morgan had assembled a fine home library comprising titles typically found on his peers’ bookshelves. But alongside modern editions of such authors as Charles Dickens and Edward Bulwer-Lytton were several items that stood out, among them autographs of the signers of the US Declaration of Independence, a handwritten letter by the poet Robert Burns, and a copy of the so-called Eliot Indian Bible, the first translation of the Old and New Testaments into an Indigenous American language.

By the 1890s Morgan was regularly visiting New York and London bookdealers and seeking out authors’ manuscripts and first editions—and even his first Gutenberg Bible.

H. S. Mendelssohn, London

J. Pierpont Morgan, undated (before 1890)

Albumen print

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 3287

Junius S. Morgan II: Nephew and Adviser

Junius Spencer Morgan II (1867–1932), son of J. Pierpont Morgan’s sister Sarah, began collecting rare books while he was in his teens and eventually built a fine collection of the ancient Roman poet Virgil’s works. An indifferent financier and ardent bibliophile, Junius became his uncle’s adviser and de facto librarian, exerting an outsize influence on the nature and scale of Pierpont’s acquisitions. It was Junius who guided Pierpont in his en bloc purchases of other collections, conferred with architect Charles Follen McKim during the Library’s design and construction, and—importantly—introduced Pierpont to Belle da Costa Greene, the librarian who would ultimately displace Junius as manager of all matters related to Pierpont’s books and manuscripts.

Gainsborough Studio, London

Junius Spencer Morgan II, ca. 1900

Albumen print

Collection of Elisabeth Morgan