Belle da Costa Greene and the Women of the Morgan

Belle da Costa Greene (1879–1950) began working as J. Pierpont Morgan’s librarian in 1905. After Morgan’s death in 1913, Greene maintained a similar role as the institution’s first director, opening the private treasure-house to the public in 1924. Her professional correspondence, catalogued only recently, offers new insight into how Greene maneuvered in a world of books and manuscripts dominated by men. It also reveals the stories of other women who worked with Greene at the Morgan Library, including Meta Harrsen, Marguerite Duprez Lahey, Dorothy Miner, Violet Napier (née Burnie), and Ada Thurston.

The letters and objects on display document the experiences of these women, who were among the small but growing number of female rare-book librarians worldwide. Greene and the women she hired were respected and widely regarded as experts in their field. Above all, these women of the Morgan were ambitious, committed to the value of their work, and well attuned to their boss’s high expectations. As the exhibition shows, however, Greene was not only a director but also a mentor and friend. Her story and legacy will be the subject of a major exhibition in 2024 to mark the Morgan’s centenary as a public institution.

This online exhibition is presented in conjunction with the installation Belle da Costa Greene and the Women of the Morgan, on view May 10, 2022 through January 8, 2023, organized by Erica Ciallela, Belle da Costa Greene Curatorial Fellow, Department of Literary and Historical Manuscripts.

A Librarian’s Office

With a view of the Library’s front doors on 36th Street, Greene’s office in the North Room served multiple purposes, from storing books to holding meetings to performing routine directorial tasks, such as signing paychecks. One of Greene’s own paychecks speaks to the wealth she earned working at the Morgan. In 1913, journalists were in awe of her $10,000 salary (about $280,000 today). Greene often remarked that her staff were paid more than those at other libraries, and she ensured yearly raises for her dedicated colleagues.

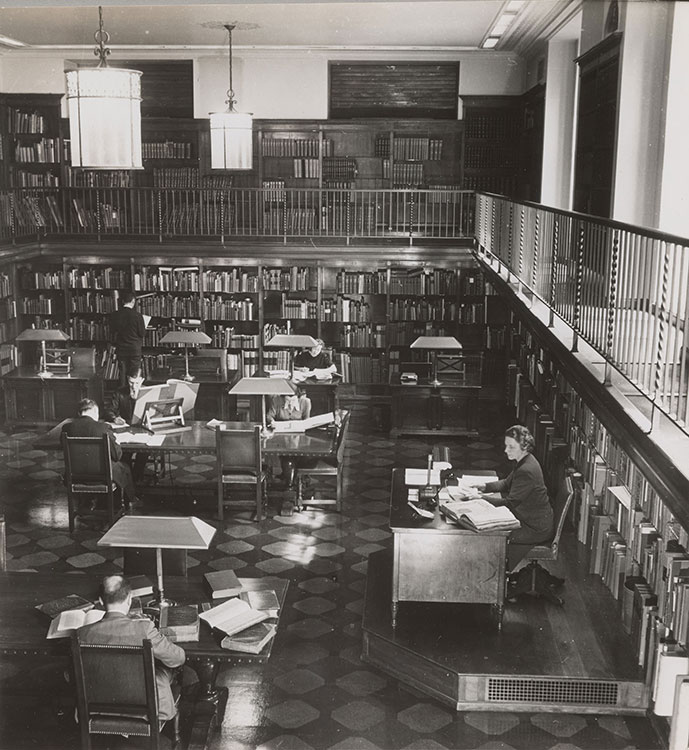

Tebbs & Knell, New York

The North Room of the Pierpont Morgan Library, [1923–ca. 1935]

TK Gelatin silver print

Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum; ARC 1600.2

Belle da Costa Greene (1879–1950)

Signed paychecks to Ada Thurston, Meta Harrsen, and herself, 1916–22

Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum

Library Work

As the Morgan’s collections and activities grew, so did the need for Greene to manage all the accompanying work efficiently. The staff list from 1943 provides a glimpse of the people Greene hired and supervised, including cataloguers, facilities staff, and curators. In most libraries across the country, the leading roles were filled by men, especially in the world of rare books and manuscripts. While it was common for librarians and library assistants to be women, the Morgan offered a rare example of a strong female-led team.

Belle da Costa Greene (1879–1950)

Typed list of staff and their duties, 1943

Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum

Walter Sanders (1897–1985)

Reading Room of the Pierpont Morgan Library, ca. 1950

Gelatin silver print

Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum; ARC 1916

Accomplishing Something of Definite Value

Greene had high standards for her employees. The director’s job often was not easy. When facing difficulties, Greene treated her colleagues with respect while considering the needs of the collection and those it served. These two letters sent to library assistants, one terminating Helen Crowe and the other promoting Meta Harrsen, reveal the qualities and ambition Greene sought in the people she hired. She even articulates a larger vision for the Morgan as a research library, an effort made by the staff “not only for herself but for the students of this country.”

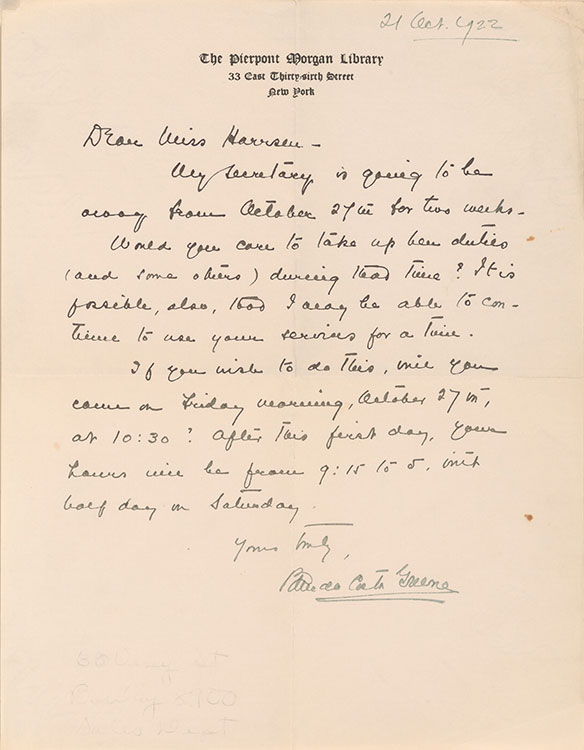

Belle da Costa Greene (1879–1950)

Letter to Helen Crowe, 1 April 1925

Letter to Meta Harrsen, 21 October 1922

Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum

From One Legacy to Another

Greene hired Dorothy Miner in 1933 to help catalogue the Morgan’s illuminated manuscript collection.Greene’s respect for her mentee can be seen through her recommendation of Miner for a position at the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore. Miner would stay at the Walters for thirty years, creating a legacy of her own. She maintained both a professional and personal friendship with Greene, often seeking her former boss’s advice. In 1954 Miner edited a festschrift honoring her mentor. Titled Studies in Art and Literature for Belle da Costa Greene, the book’s essays range in topics from medieval manuscripts to Dutch paintings, covering each of the Morgan’s collection focuses at the time.

Belle da Costa Greene (1879–1950)

Retained copy of letter to Sarah Wharton Jones Walters of the Walters Art Gallery, 12 December 1934

Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum

Women-led

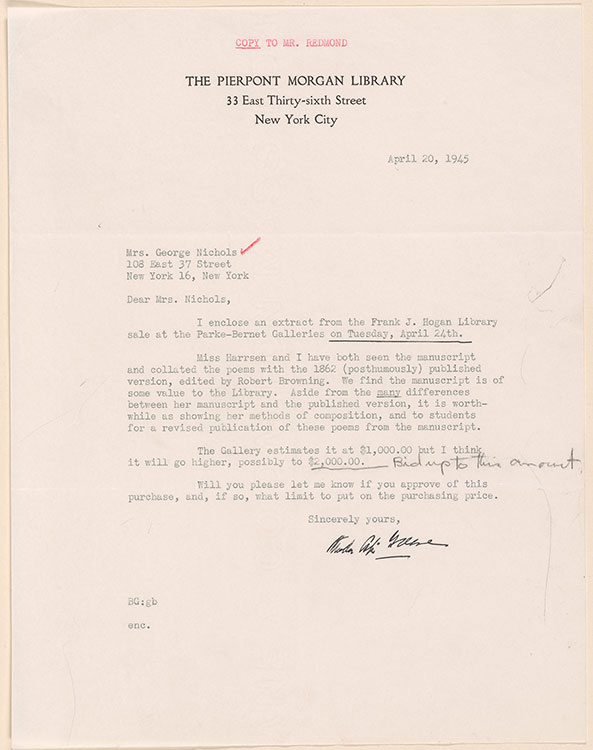

A medieval scholar, Meta Harrsen headed the illuminated manuscript collection at the Morgan during the 1940s and ’50s. Greene often relied on Harrsen to answer inquiries, as seen in the memo about the Tarot cards made for a member of the Visconti-Sforza family. Harrsen would spend her career at the Morgan, helping run the Reading Room, responding to research requests, and consulting on numerous acquisitions, such as the Elizabeth Barrett Browning manuscript described in the letter to Jane Nichols. The eldest daughter of J. P. Morgan Jr., Nichols was acting president of the board in 1945, adding to the legacy of strong women leading the Morgan.

Belle da Costa Greene (1879–1950)

Note to Meta Harrsen, 23 February 1945

Letter to Jane Nichols, 20 April 1945

Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum

Bonifacio Bembo

The Popess, from “Visconti-Sforza Tarot Cards”

Italy, Milan, ca. 1450–80

Painting, on vellum

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1911; MS M.630.3

Bonifacio Bembo

Queen of Cups, from “Visconti-Sforza Tarot Cards”

Italy, Milan, ca. 1450–80

Painting, on vellum

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1911; MS M.630.16

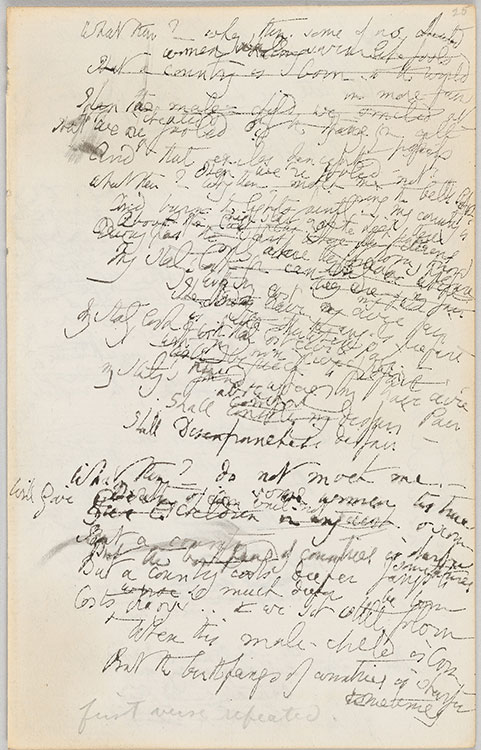

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806–1861)

Last Poems

Pages from the autograph manuscript, ca. 1860

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased in 1945; MA 1211

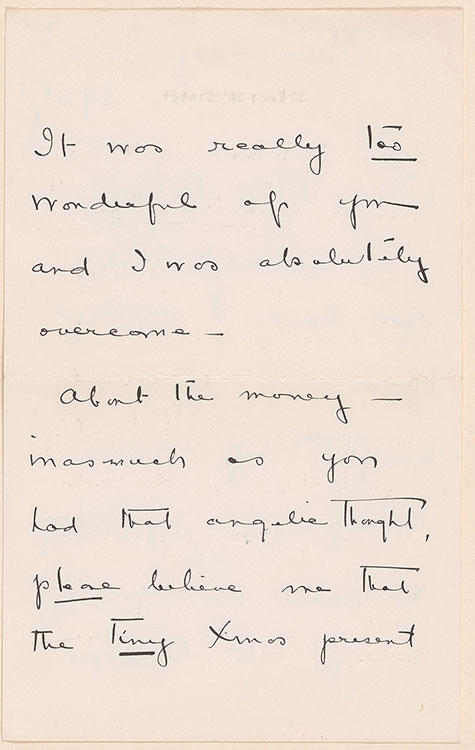

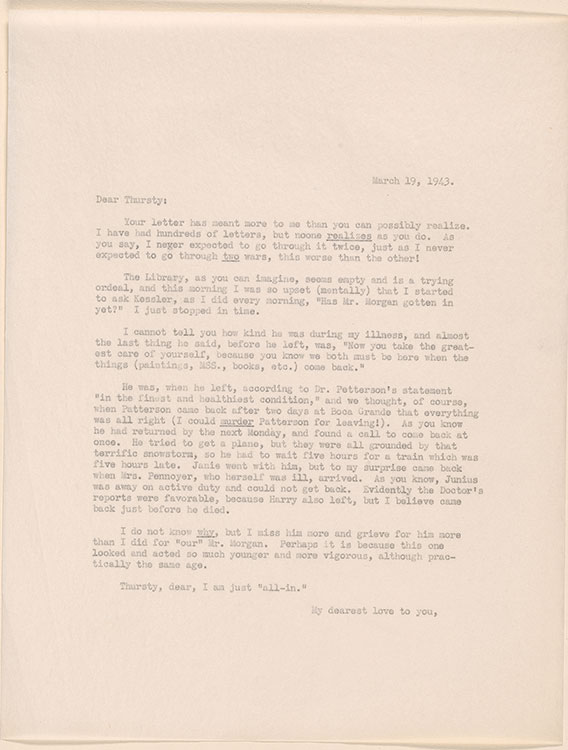

Trusted Confidants

Greene formed deep bonds with her female colleagues. Marguerite Duprez Lahey, a bookbinder, was a confidant to Greene, who in this letter shared her daydreams of running away to Europe. Ada Thurston, Greene’s assistant and first hire after becoming librarian, would remain a close friend even after leaving the Morgan. Written following the death of J. P. Morgan Jr., the letter to Thurston, affectionately called “Thursty,” shows a profound connection between the two women as well as the personal importance of the Morgan Library in their lives.

Belle da Costa Greene (1879–1950)

Letter with envelope to Marguerite Duprez Lahey, 16 June 1927

Retained copy of letter to Ada Thurston, 19 March 1943

Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum

Collection Development

Today the Morgan has the largest collection of Rembrandt prints in North America, thanks in part to Greene’s efforts to acquire the Dutch artist’s work: thirty-one etchings came to the museum between 1924 and 1929. While Greene was traveling, her secretary and assistant Violet Burnie (later Napier) received word of a Rembrandt print for sale. To ensure the piece wasn’t sold, Burnie, followed her boss’s guidance and had the print sent for inspection, cabling the decision to Greene. Greene’s staff was well versed in the strengths and needs of the collection and often helped identify new acquisitions.

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (1606–1669)

A Scholar in His Study (‘Faust’), ca. 1652

Etching, engraving, and drypoint

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased from Gilhofer & Ranschburg via Schab, 2 September 1929; RVR 360

Violet Burnie

Note to Belle da Costa Greene, 1929

Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum

Mentor and Friend

Violet Napier worked at the Morgan from 1925 to 1932 as a secretary and library assistant. After leaving the institution, Napier remained close friends with Greene and often brought her son to visit her former boss. Napier recalled her time at the Morgan in this note, remarking on the woman who helped shape her early career. The print of French painter Paul Helleu’s 1913 sketch of Greene, given to Napier as a wedding present, further reflects the lasting affection between mentor and mentee. The portrait, like most images of Greene, dates from her early days at the Morgan. She often turned down requests for photographs later in her career, explaining that the Library itself should remain the public focus.

Paul Helleu (1859–1927)

Portrait of Belle da Costa Greene [reproduction], 1913

Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum; ARC 3197

Violet Napier

Autograph note, 1977

Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum; ARC 3197.1

Leaving a Legacy

After nearly forty-four years, including twenty-five as director, Greene said goodbye to the Morgan. Having formed close relationships with her staff, she knew she was leaving the collection and her legacy in well-trained and loyal hands. Known for crediting others with the Library’s success, she continued to diminish her own role, writing to her colleagues, “It is wonderful of you all and makes me feel (at last) very ‘humble’ and very proud at the same time.” Under Greene, the Morgan added over seventeen thousand reference works and ten thousand printed books to its collection, presented forty-six exhibitions, issued thirty-five publications, started a lecture series, and provided scholars with access to some of the world’s most incredible cultural artifacts.

Tebbs & Knell, New York

Reading Room of the Pierpont Morgan Library, [1923–ca. 1935]

TK Gelatin silver print

Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum; ARC 1914

Belle da Costa Greene (1879–1950)

Letter to Pierpont Morgan Library staff, 5 April 1949

Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum