Capturing Likeness, Constructing Identity

In the late summer of 1526, Holbein set his sights on England, bearing letters of introduction from Erasmus to prominent local figures. His journey first took him to Antwerp, the leading economic and cultural hub in the Netherlands, where he encountered works by artists such as Jan Gossaert and Quentin Metsys, also on view in this gallery.

Holbein reached London that fall. Highly skilled portraitists were rare in the country, and he had few rivals. During his first stay, which lasted until 1528, Holbein produced several large-scale likenesses in which he delineated facial features with incisive accuracy. The painter placed his sitters in splendid spaces, surrounded by carefully selected and realistically rendered still-life elements. Through his command of the medium of oil paint, he captured a sense of immediacy and illusionism, seductively rendering a wide range of textures—from flesh to fur.

Mary, Lady Guildford

Mary Wotton, Lady Guildford (1499–after 1527), calmly gazes at the viewer from within a grand setting embellished by a marble column decorated in an Italianate style. She and her husband, Sir Henry Guildford, were among Holbein’s most important patrons during the artist’s first stay in England. While the sophisticated backdrop, jewelry, and fashionable dress, painted using lavish quantities of gold, denote Lady Guildford’s social status, the portrait also aims to communicate her piety and virtue. She clutches a religious book and a rosary, as if caught in a moment of reading or praying. The sprig of rosemary attached to her bodice is a traditional symbol of remembrance.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Mary, Lady Guildford, 1527

Oil on panel

Saint Louis Art Museum, Museum Purchase; 1:1943

The Myrroure of the Blessyd Lyf of Jhesu Cryste

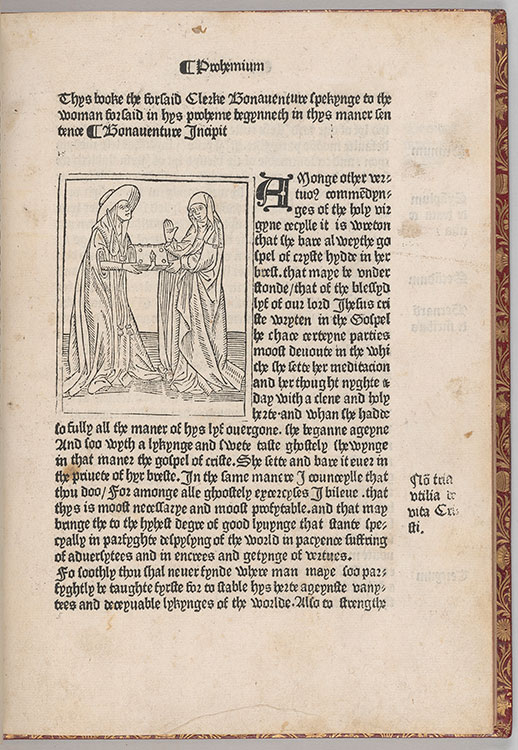

Written in an animated and accessible style, this popular work, long attributed to St. Bonaventure, encourages readers to reflect on mortality—hence the “mirror” in the English title—and contemplate the episodes of suffering that led up to Christ’s death. The woodcut illustration shows St. Bonaventure giving the book to a woman, suggesting that the text was specifically intended for a female readership or that this edition was particularly marketed to women. In Holbein’s portrait of Lady Guildford, the sitter holds what might be a copy of this text: an elegant green volume with a tasseled bookmark, labeled by Holbein with its Latin title, Vita Christi (Life of Christ), along the book’s top edge.

Johann de Caulibus (b. ca. 1376)

The Myrroure of the Blessyd Lyf of Jhesu Cryste

Translated by Nicholas Love (d. ca. 1423)

Westminster: William Caxton, ca. 1489–90

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased with the Bennett collection, 1902; PML 701

A Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling (Anne Lovell?)

Although this panel is one of Holbein’s masterpieces, the dignified sitter, dressed in an ermine fur cap and a fine silk shawl, remained unidentified until 2004, when the animals in the portrait were recognized as likely references to the Lovell family. Anne Lovell (née Ashby; d. 1539) was a wealthy English noblewoman whose husband, Sir Francis Lovell, served King Henry VIII. Her pet red squirrel, restrained by a silver chain and nibbling a hazelnut, alludes to the squirrels on the Lovell family crest. The starling on the left is a play on East Harling (commonly spelled as “Estharlyng” in Tudor times), the location of the Lovell estate in Norfolk, England. Technical studies have shown that Holbein added the animals at a late stage in the painting process, very likely at the request of the patrons.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

A Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling (Anne Lovell?), ca. 1526–28

Oil on panel

National Gallery, London, bought with contributions from the National Heritage Memorial Fund and the Art Fund and Mr. J. Paul Getty Jnr. (through the American Friends of the National Gallery, London), 1992; NG6540

A solemn young woman holds a red squirrel in her hands, while a glossy-feathered starling perches on a branch near her shoulder. Although squirrels and starlings were common pets in England at the time, in this work, they also function as heraldic symbols and provide clues to the identity of the sitter. She is thought to be Anne Lovell—a wealthy and well-connected woman from Norfolk, whose husband Francis served King Henry VIII as an “esquire of the body,” or personal attendant.

Most sixteenth-century portraits of female sitters were originally created as part of a pair, with the woman placed to the viewer’s right side and gazing towards the left, in the direction of her husband. Anne Lovell’s portrait defies this convention, which suggests that it was likely painted as an independent work. The portrait might have been commissioned to celebrate the birth of the couple’s son Thomas in the spring of 1526.

Holbein’s facility with oil paint is evident throughout the portrait. Note, for instance, the dab of white paint that he added to the squirrel’s large dark eye, creating the impression of a bright, glassy surface. While the animal’s loosely painted chain falls through the sitter’s fingers, its fluffy tail reaches toward the opening in the woman’s chemise, resulting in a tactile juxtaposition of fur and flesh.

Some of the changes that Holbein made while painting are visible to the naked eye. You can see that he pulled the woman's hairline back at her temples, revealing more of her forehead. Other alterations are now hidden under layers of paint and can only be observed with the help of x-radiography. We know, for instance, that the artist had to change the position of the sitter’s arms fairly late in the painting process. This was done to accommodate the addition of the squirrel, which was likely requested by the patrons themselves.

© The National Gallery, London

Sir Nicholas Carew

Sir Nicholas Carew (ca. 1496–1539) carried out several important diplomatic missions in the service of Henry VIII. Made with a painted portrait in mind, this study exemplifies Holbein’s approach to drawing during his first stay in England. Working on a large scale and concentrating his attention on Carew’s face and beard, the artist modeled the man’s features by carefully blending black and colored chalks. Other parts of the drawing, such as the sitter’s upper body and the fluffy feathers that adorn his hat, are described using swiftly drawn yet virtuosic lines. The headgear is covered entirely in black chalk, but the letters gl, inscribed on the headband, would have reminded Holbein that the garment’s actual color was either yellow (gelb) or gold (gold).

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Sir Nicholas Carew, 1527

Black and colored chalks

Kunstmuseum Basel, Kupferstichkabinett, Amerbach-Kabinett 1662; 1662.34

Before 1539—when he was accused of participating in a conspiracy to overthrow King Henry VIII and beheaded at Tower Hill—Nicholas Carew enjoyed a very successful career as a courtier and diplomat. He was one of the king’s closest associates and undertook a number of important diplomatic missions, even accompanying Henry to his famous meeting with the French King Francis I at the Field of the Cloth of Gold in 1520.

This large, brilliantly preserved drawing focuses on Carew’s physiognomy and luscious beard. It belongs to a small group of portrait studies in colored chalks, which Holbein produced during his first stay in England. Although the artist had begun experimenting with the medium only a few years prior, the skillful blending of different colors attest to his great mastery. Carew’s skin is modeled using a combination of red and black chalks, achieving an almost three-dimensional appearance. The armor and the opulent feathers that adorn his hat, on the other hand, are done more swiftly, with the greatest economy of means.

Kunstmuseum Basel Martin P. Bühler

Portrait of a Scholar

With his right hand raised and his left resting on a book and clutching a pair of glasses, the scholar in Quentin Metsys’s painting appears to have been caught at a moment of revelation. His dynamic pose and bold physicality distinguish the man from Holbein’s more stoic, seemingly withdrawn sitters, such as Erasmus and Sir Thomas More. The scholar is situated against a window, with a carefully constructed vista extending into the distance, including a river, a forest, mountains, and a fortified city. Such views, known as world landscapes, were a specialty of Antwerp painters in the 1520s.

Quentin Metsys (1465/66–1530)

Portrait of a Scholar, ca. 1525–30

Mixed technique on panel

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main; 766

Photo: Städel Museum

Francisco de los Cobos y Molina

Jan Gossaert depicted this self-possessed sitter with a red cross emblazoned on his doublet, a gem-encrusted jewel shaped like a scallop shell hanging around his neck, and an intricate hat badge. Despite such seemingly specific attributes, the man’s identity was lost until the late twentieth century, when he was recognized as Francisco de los Cobos y Molina (ca. 1475/80– 1547), the powerful secretary and advisor to Emperor Charles V. The identification was made by comparing the painting with the portrait medal of Los Cobos.

Jan Gossaert (ca. 1478–ca. 1532)

Francisco de los Cobos y Molina, ca. 1530–32

Oil on panel

Inscribed on hat badge, in Latin: Augusta Livia [wife of the Roman Emperor Augustus] V Carolus V [?]

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; 88.PB.43

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Portrait Medal of Francisco de los Cobos

Portrait medals, which unite a likeness, text (usually name and motto), and personal emblem, can play an important role in identifying distinguished individuals. This medal and its inscription reveal the subject of Jan Gossaert’s corresponding painting. Although it can be challenging to directly compare works of such different mediums, the men’s facial features, hairstyles, and beards appear strikingly similar. Moreover, in both images the sitter wears the scallop-shell pendant of the Order of Santiago, of which Los Cobos was comendador mayor (major commander).

Christoph Weiditz the Elder (ca. 1500–1559)

Portrait Medal of Francisco de los Cobos (obverse), 1531

Lead

Inscribed around the circumference, in Latin: To Francisco de los Cobos, great chancellor of the imperial army, privy councilor of Charles the fifth, in the year 1531

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection; 1957.14.1183.a

Christoph Weiditz the Elder (ca. 1500–1559)

Portrait Medal of Francisco de los Cobos, with a Man Riding toward a Cliff, Carrying a Scroll (reverse), 1531

Lead

Inscribed on the scroll, in Latin: Fate will find a way

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection; 1957.14.1183.b

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington