Erasmus, More, and the Humanist Portrait

Desiderius Erasmus (1466?–1536), also known as Erasmus of Rotterdam, was Europe’s first celebrity scholar, famous for his theological and philosophical writings. His ideas were widely and rapidly disseminated through the relatively new technology of the printing press. His books, such as the satirical Praise of Folly (Moriae encomium), were best sellers, read avidly across the social spectrum.

Although Erasmus believed that the written word was superior to the visual image, he used his portraits strategically to extend and deepen his influence. Erasmus’s personal emblem was Terminus, the Roman god of boundaries, known for resisting Jupiter, king of the gods. Artists, notably Holbein and Quentin Metsys, represented Terminus and Erasmus as a pair, so that the god’s portrayal as a stern-faced herm (stone pedestal with a head) came to embody the scholar’s formidable character. Erasmus was Holbein’s most important early supporter, and he introduced the painter to prominent individuals in England, including Sir Thomas More, a scholar and an advisor to King Henry VIII.

Erasmus of Rotterdam, Oil on panel

In 1523 Holbein developed a portrait of Erasmus that reflected the sitter’s scholarly reputation. Holbein portrayed Erasmus in three-quarter pose and dressed in a black robe and hat, emphasizing his intellectual character through the strong jawline and deep-set eyes. This circa 1532 painting of the then sixty-two-year-old humanist was based upon that earlier image but sensitively adjusted to convey Erasmus’s advanced age. His cheeks are more sunken, his forehead is wrinkled, and snow-white hair now peeks from underneath his cap. Such portrait roundels often served as intimate gifts between family members or close friends. This example was in the possession of Hieronymus Froben, son of the printer Johann Froben and Erasmus’s godson.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Erasmus of Rotterdam, ca. 1532

Oil on panel

Kunstmuseum Basel, Amerbach-Kabinett 1662; 324

Desiderius Erasmus was perhaps the first celebrity author in Europe, whose books on theology, philosophy, and the classics were published by the thousands on an almost annual basis. Although educated as a priest, he spent his early years as a peripatetic professor at universities in Cambridge, England, Turin, Italy, and Leuven, Belgium. A central figure of the European Renaissance, Erasmus corresponded with humanist luminaries from England to Italy, and counselled kings and church leaders.

Although Erasmus often argued for the primacy of word over image in the representation of an individual, he had a clear understanding of the power of the visual arts. He commissioned the artists Quentin Metsys and Albrecht Dürer to portray him as a scholar and author, but it was Holbein the Younger who created the de facto portrait of the great humanist. The artist and his Basel workshop produced multiple images of Erasmus, including this small roundel of the older Erasmus, attributed exclusively to the hand of Holbein himself. Devoid of any overt symbols or objects, the portrait focuses upon the face of the scholar—the man himself—rather than his occupation.

Kunstmuseum Basel - Jonas Haenggi

Signet Ring of Erasmus

Erasmus received this ring, set with an ancient carved gem, as a gift from his student Alexander Stewart, the archbishop of St. Andrews, Scotland. Erasmus believed the figure on the gem to be Terminus, the popular Roman god of boundaries known for his firm opposition to Jupiter, who tried to expel Terminus from the Capitoline Hill in Rome. Intrigued by this model of fortitude (and obstinance), Erasmus took Terminus as his personal emblem. The figure on the gem, however, has now been identified as Dionysus, god of wine.

Unknown maker

Signet Ring of Erasmus of Rotterdam (and modern impression), before 1509

Gold and carnelian (Roman gem, 1st century AD)

Historisches Museum Basel; 1893.365

©Historisches Museum Basel, Peter Portner

Seal of Erasmus of Rotterdam

Erasmus had this seal made to press his emblem into the warm wax that fastened his correspondences and other documents. Here Terminus is represented simply as a herm, a pedestal with a head. An inscription on the base identifies the Roman god while his head is framed by an abbreviated form of Erasmus’s personal motto, Cedo nulli (I yield to no one).

Unknown maker

Seal of Erasmus of Rotterdam (and modern impression), ca. 1513–19

Silver

Historisches Museum Basel; 1893.364

©Historisches Museum Basel, Peter Portner

Erasmus of Rotterdam, Engraving

Albrecht Dürer depicted the humanist scholar standing in his book-filled study and writing a letter. Although the inscription asserts that the likeness was “done from life,” the two men did not meet for an in-person sitting. Instead, Dürer based the portrayal on a drawing he had made during his meeting with Erasmus years earlier and on Quentin Metsys’s medal, while the composition evokes Holbein’s earlier portraits of the scholar writing at his desk. Ultimately, Erasmus did not care for Dürer’s representation and complained about it to friends.

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

Erasmus of Rotterdam, 1526

Engraving

Inscribed on the wall panel behind Erasmus, in Latin and Greek: The likeness of Erasmus of Rotterdam, done from life by Albrecht Dürer. His writings present a better portrait / 1526 / AD

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Rosenwald Collection; 1943.3.3554

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

Portrait Medal of Erasmus of Rotterdam

Portrait medals were a form of portable sculpture popular in the Renaissance. Erasmus commissioned the design for this large and impressive medal from the Antwerp painter Quentin Metsys, who combined Erasmus’s likeness with that of his emblem, the Roman god Terminus. Attired in a cap and collared robe, Erasmus appears in profile, as if on an ancient coin. The surrounding inscription relates to the long-standing humanist debate about the respective merits of images and texts. It asserts that although the portrait is “from life,” and therefore reliable, Erasmus’s writings provide a truer representation of the author.

Seen in profile, facing into the winds of adversity, Terminus aligns with Erasmus’s portrait on the obverse. In Christian thought, Terminus was associated with the boundary between life and death. Turning the medal over, from the portrait of Erasmus to the image of Terminus, encouraged consideration of the inevitable passage from life to death, the true terminus.

Quentin Metsys (1465/66–1530), designer

Portrait Medal of Erasmus of Rotterdam (obverse), 1519, cast ca. 1524

Bronze

Inscribed around the perimeter, in Greek and Latin: His writings will give a better picture: His portrait taken from life.

Historisches Museum Basel; 1916.288

Quentin Metsys (1465/66–1530), designer

Portrait medal of Erasmus of Rotterdam, with Terminus (reverse), 1519, cast ca. 1524

Bronze

Inscribed around the perimeter and center, in Greek and Latin: Look to your end, however long your life—death is the final boundary of things.

Historisches Museum Basel; 1916.288

©Historisches Museum Basel, Peter Portner

Terminus, Device of Erasmus

In this painting, Holbein combined Erasmus’s portrait with his emblem, providing Terminus with Erasmus’s facial features. Seen through a stone opening, Erasmus/Terminus gazes across a featureless landscape. The golden disk behind his head represents divine radiance, underscoring the Christian meaning of the emblem for Erasmus: steadfast character and unwavering faith. This rare painting of a personal emblem by Holbein was probably intended to delight an admirer rather than to gratify Erasmus himself.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Terminus, Device of Erasmus, ca. 1532

Oil on panel

Inscribed on the background, in Latin: I yield to none

Inscribed on the base of the herm, in Latin: Terminus

Cleveland Museum of Art, gift of Dr. and Mrs. Sherman E. Lee in memory of Milton S. Fox; 1971.166

Terminus appears repeatedly in images associated with Erasmus. The deity, depicted as a bust emerging from a stone pillar, was venerated by ancient Romans as a protector of boundaries and frontiers. In Christian thought, Terminus was associated with the boundary between life and death.

For his personal emblem, Erasmus combined the iconography of the Terminus with the motto “concede nulli”—meaning I concede, or yield, to no one. Some of his contemporaries interpreted it as an expression of superiority and accused the scholar of intellectual and moral arrogance. Nevertheless, the image attained great renown and could even serve as the celebrated humanist’s visual surrogate. It was disseminated across Europe through prints, medals, and paintings, such as this exquisite roundel. Although Erasmus worked closely with Holbein and commissioned a number of works directly from the artist, the patron of this panel was most likely not the scholar himself but one of his many admirers.

The Cleveland Museum of Art

Erasmus of Rotterdam, Oil on panel

To satisfy the great demand for likenesses of Erasmus among the scholar’s many patrons and admirers, Holbein and members of his Basel workshop produced numerous versions of the same image. Like the other painted representation of Erasmus on view in the exhibition, this portrait shows the scholar in three-quarter profile against a neutral background. Holbein achieved a stately monumentality by filling the narrow panel with Erasmus’s form and by depicting his austere but luxurious clothing: the black hat and voluminous robe with fur collar and cuffs.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543) (and workshop?)

Erasmus of Rotterdam, ca. 1532

Oil on panel

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Robert Lehman Collection; 1975.1.138

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Erasmus of Rotterdam, Woodcut

Holbein designed this commemorative portrait of Erasmus following the latter’s death in 1536. Seen in full length and dressed in long robes, the scholar rests his hand on a sculpted herm of Terminus, which seems to cast a wily glance at the viewer. The lavishly decorated triumphal arch honors Erasmus, while the motifs of baskets and abundant garlands of fruit allude to his prolific scholarship. The text, added in movable metal type (not part of the woodcut itself ), commends the accuracy of the portrait: “If you have not seen Erasmus in life, then this image, executed from life, will show you how he looked.”

Veit Specklin (d. 1550), blockcutter, after a design by Hans Holbein the Younger

(1497/98–1543)

Erasmus of Rotterdam (“im Gehäus”), ca. 1538–40

Woodcut

Kunstmuseum Basel, Kupferstichkabinett; X.2128

Kunstmuseum Basel - Jonas Haenggi

Johann Froben

Despite its small scale, Holbein’s posthumous portrait of Johann Froben (1460–1527), originally enclosed in a carved frame with a lid, conveys the determined character of the Basel printer. It is one of the first known portraits of a European book printer, suggesting the importance of Froben to the printing industry as well as to Holbein’s career. Erasmus entrusted the publication of most of his texts to Froben, whose enterprise influenced book production throughout Europe. Froben hired Holbein to design woodcut illustrations for his publications beginning in 1516.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Johann Froben, ca. 1528–32

Oil and tempera on panel

Private collection

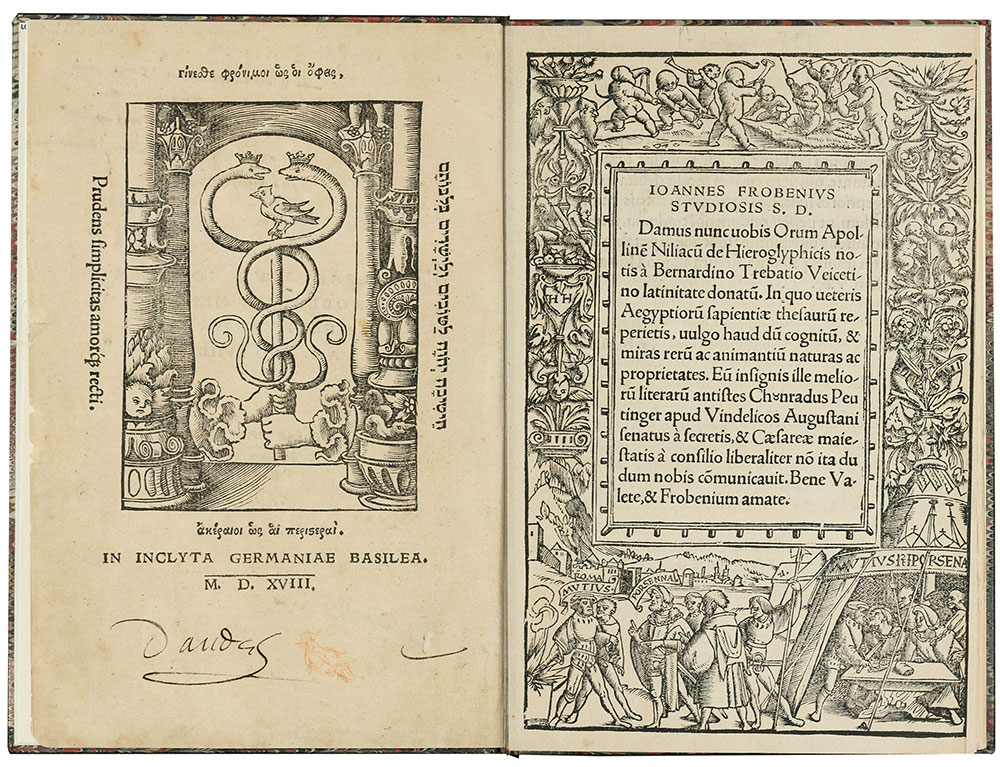

Hieroglyphica

Starting in 1516, Holbein designed decorative borders and illustrations for the Basel printer Johann Froben. This imagery, often derived from classical sources, was intended to appeal to a cultured clientele but did not directly relate to the text itself. Here, the shield in the left border contains the initials HH, which stand for either Hans Holbein or Hans Herman, the blockcutter who translated Holbein’s drawing into a relief woodblock for printing. Facing the title page is Froben’s printer’s mark, the trademark of his press. The caduceus (staff ) of the god Mercury represents industry and commerce, while the dove and serpents are derived from Matthew 10:16, which is printed in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew: “Be you therefore wise as serpents and harmless as doves.”

Horapollo (5th century AD)

Hieroglyphica

Woodcut by Hans Herman (act. 1516–23), after a design by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Basel: Johann Froben, 1518

Getty Research Institute, Special Collections, Los Angeles; 2864-782

Getty Research Institute

Henry VIII, King of England

The books Johann Froben printed were distributed across Europe, which meant that Holbein’s illustrations (if not his name) were disseminated as well. In 1521 the London printer Richard Pynson had an exact copy of the Mucius Scaevola border produced for his own use. Although the initials HH were retained, Pynson was likely more interested in emulating the quality of Froben’s production than Holbein’s artistic creation. In fact, many title-page borders used by the Basel printers—those designed by Holbein and others—were copied across Europe in efforts to capitalize on the notoriety of Basel printing.

Henry VIII, King of England (1491–1547)

Assertio septem sacramentorum adversus Martin Lutherum (Assertion of the seven sacraments in opposition to Martin Luther)

Woodcut after a design by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543) London: Richard Pynson, 12 July 1521

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of J. P. Morgan, 1935; PML 32270

Sir Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (1478–1535) sat for this portrait at the height of his political career, shortly before he was promoted to lord chancellor, the highest-ranking office in Tudor England. Like his friend Erasmus, More was a prolific scholar, but Holbein presents him as an authoritative statesman, prominently adorned with a gold livery chain— a symbol of his service to the king. The S-shaped links might stand in for the motto “Souvent me souvient” (Think of me often), while a Tudor rose at the center is the traditional heraldic emblem of England. The portrait displays Holbein’s ability to render colors and textures—from More’s graying stubble to the opulent fur trim of his coat and the lush, voluminous red-velvet sleeves of his doublet.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Sir Thomas More, 1527

Oil on panel

The Frick Collection, New York, Henry Clay Frick Bequest; 1912.1.77

Erasmus was a close friend of Sir Thomas More and had stayed at the More house in Chelsea during his visits to London. A lawyer, scholar, and a powerful counselor to the King, More was Holbein’s most important supporter during his first visit to the British Isles. Upon his arrival in England, the artist carried letters of introduction from Erasmus to More in the hopes of using this personal connection to gain work in London and at the Tudor court. More introduced Holbein to several important courtiers who all commissioned portraits from him, including the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Warham, Royal Astronomer Nicholas Kratzer, and Sir Henry Guildford and his wife, Mary. Mary Guildford’s portrait is on view in the gallery to your left.

This is the canonical portrait of one of the key figures in sixteenth-century England. More is depicted in a three-quarter view, similar to Holbein’s favored pose for Erasmus. The man’s imposing form fills nearly the entire panel. The fairly dark palette of More’s fur-lined velvet robe and the green drapery behind him heighten the focus on the sitter’s face and intent gaze. The astonishing realism of Holbein’s portrayal extends to More’s salt-and-pepper whiskers.

Besides the painting of Thomas More is a copy of his most famous book, Utopia. Although divorce was legal in More’s Utopia, he did not support Henry VIII’s desire to separate from the Roman church so that Henry could divorce his wife, Catherine of Aragon, to marry Anne Boleyn. Henry saw this as treason, thus leading to More’s fall from power and execution in 1535.

The Frick Collection. Photo : Michael Bodycomb

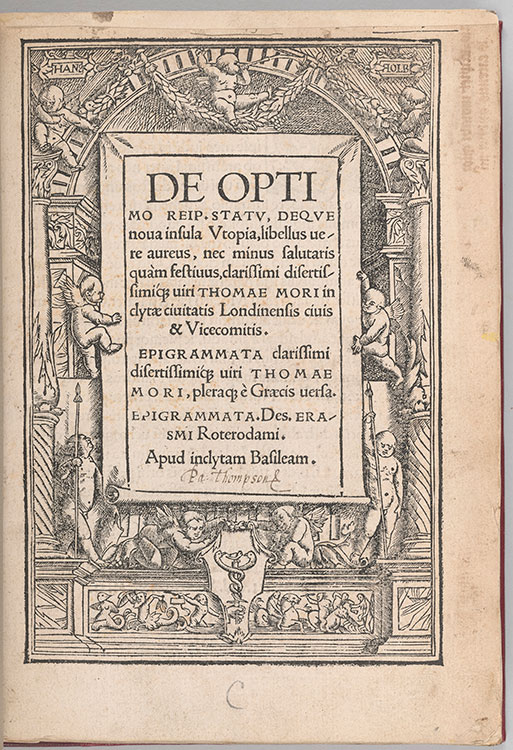

Utopia

During a stay in Antwerp in 1515, Sir Thomas More began drafting a literary work that described a self-contained society on a fictional island. He coined the term “utopia” based on the ancient Greek term ou-topos, meaning “no place.” Both playful and serious, rooted in satire but also exploring complex philosophical ideas, the text was edited by his friend Erasmus and first published in Antwerp in 1516. The revised Basel edition, on view here, was published by Johann Froben under the continued guidance of Erasmus. It included a new map showing a bird’s-eye view of the island designed by Hans Holbein’s older brother, Ambrosius, and reused a title page border that Hans designed in 1516.

Sir Thomas More (1478–1535)

Utopia

Woodcut title page border by Hans Hermann (active 1516–23), after a design by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543)

Basel: Johann Froben, November and December 1518

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1912; PML 19444