Conversations in Drawing: Seven Centuries of Art from the Gray Collection

Spanning seven hundred years of Western art, this exhibition traces the long and distinguished history of one medium: drawing. It features highlights from the remarkable collection assembled over fifty years by Richard Gray, one of America’s foremost art dealers, and the art historian Mary L. Gray.

The Gray Collection encompasses drawings produced in Europe and the United States from the fifteenth to the twenty-first century. The human figure, expressed directly and intimately, is the collection’s primary focus, demonstrating the capacity of drawing to represent and interpret the body. While there are numerous works by established artists—Rubens, Boucher, Degas, Van Gogh, Seurat, Matisse, Picasso, and Hockney, among others— the Grays were more interested in skill than celebrity, and they also collected many exceptional drawings by lesser- known draftsmen.

Often keenly aware of their place in art history, the artists in the collection engaged in lively conversations on paper with contemporaries and forebears. Other visual connections are apparent only in hindsight, a point of view afforded by the chronological breadth of the Gray Collection. Juxtaposing drawings from distinct periods and places, this exhibition illuminates the affinities and tensions that have emerged throughout the medium’s evolution.

Conversations in Drawing: Seven Centuries of Art from the Gray Collection was organized by The Art Institute of Chicago in cooperation with the Morgan Library & Museum.

The exhibition is made possible by an anonymous donor, with additional support from the Charles E. Pierce, Jr. Fund for Exhibitions, and assistance from Mr. and Mrs. Clement C. Moore II and Hubert and Mireille Goldschmidt.

Colin B. Bailey: Hello, I'm Colin B. Bailey, director of the Morgan Library and Museum, and I'm delighted to welcome you to Conversations in Drawing: Seven Centuries of Art from the Gray Collection. This exhibition brings together some 60 extraordinary works on paper, collected by Richard and Mary L. Gray. Richard Gray was an art dealer and collector who lived in Chicago, his wife Mary Gray, an art historian. Focusing primarily on the human figure, the collection spans the 15th through the 21st centuries and includes sheets made in Europe and the United States. As you move about the gallery, look for the audio symbols to hear additional information about the works. They will highlight some of the conversations that take place, whether intentionally or not, between drawings from different periods and different places. Thank you for joining us at the Morgan. We hope you enjoy your visit.

Overview

Gallery Images

François Boucher

The focus of this powerful drawing is not Boucher’s model but the yards of voluminous cloth enveloping her, resulting in a study that approaches abstraction. The artist used black chalk to create an outline and shadows, white chalk to produce shimmering highlights, and buff-colored paper to suggest flesh and give the fabric color and volume. The figure’s carefully considered pose is graceful yet monumental, delineating a semicircle with her upper body and arms. The study may have served as the model for Cleopatra in Boucher’s etched frontispiece for an edition of the French playwright Pierre Corneille’s tragedy Rodogune: Princess of Parthia.

François Boucher

French, 1703–1770

Study of a draped woman leaning on a pedestal,1759–61

Black chalk, with stumping, and white chalk, on buff paper

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.835

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Art Institute of Chicago Imaging Department

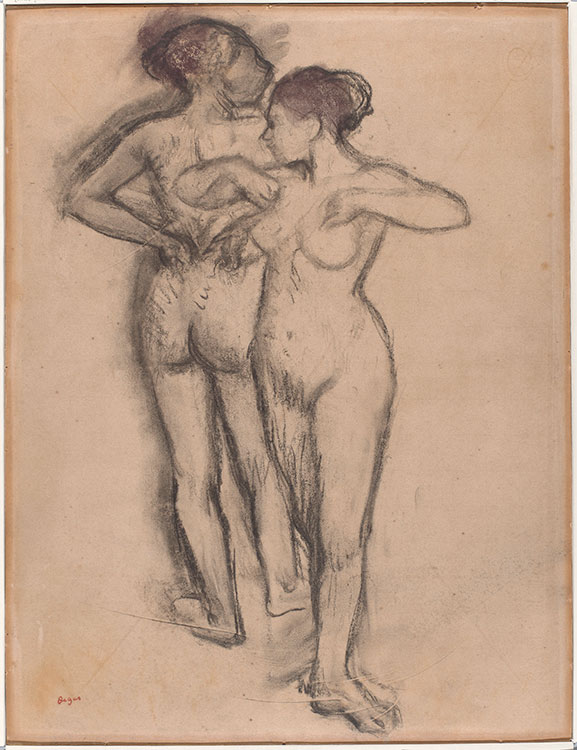

Edgar Degas

Ballet dancers were a central theme of Degas’s oeuvre beginning in the 1870s; to him, the art form uniquely embodied both classical grace and modern realism. The artist—who once self- deprecatingly said, “My chief interest in dancers lies in rendering movement and painting pretty clothes”—adopted a more formal approach to the figure in his later years. On this sheet, visible erasures show Degas's process as he subtly shifted the positions of the two models, who appear to be adjusting invisible bodices.

Edgar Degas

French, 1834–1917

Study of Dancers, 1895–1900

Charcoal and pastel on pale- pink paper (discolored to tan)

Gray Family Collection

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

Austeja Mackelaite: I'm Austeja Mackelaite, the Annette and Oscar de la Renta Assistant Curator of Drawings and Prints. Nearly half of all the works that Degas produced over the course of his life were dedicated to the ballet. His early images present dancers in the studio and stage, often wearing snug bodices and lacy tutus. In this late drawing, however, the models are nude set against the blank page and divorced from a narrative context. Using a piece of charcoal, Degas drew and redrew the contours of the overlapping figures, resulting in lines that are heavy and almost tactile. The smudges and erasures around the head, left leg and arm of the woman seen from behind allow us to trace his adjustments to her position. Touches of maroon pastel in the hair give some color to this otherwise monochromatic sheet. Despite the artist's rough, bald handling, he's able precisely to convey the movements of the women as they adjust their imaginary bodices. In contrast, the Degas figures, the woman in the Boucher drawing nearby is swaddled in layers upon layers of carefully modeled drapery. She looks pensive, almost dejected, as she gazes downward. Boucher's delicate marks contrast with the unstable silhouettes of Degas' dancers, which seem to vibrate on the page.

Henri Matisse

This woman is one of two in Matisse’s painting La musique, which he also completed in 1939. Though called a study, the drawing was an exercise in invention and variation, a way for Matisse to organize his thoughts and clarify his means before returning to the painting. There is a tactile quality to Matisse’s exploration, seen in the velvety charcoal deposits within the dark outline of the model’s features, her softly smudged skin and hair, and the brilliant areas of white left to describe her dress.

Henri Matisse

French, 1869–1954

Study of a Woman, 1939

Charcoal

Richard and Mary L. Gray, promised gift to the Art Institute of Chicago

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

© 2021 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

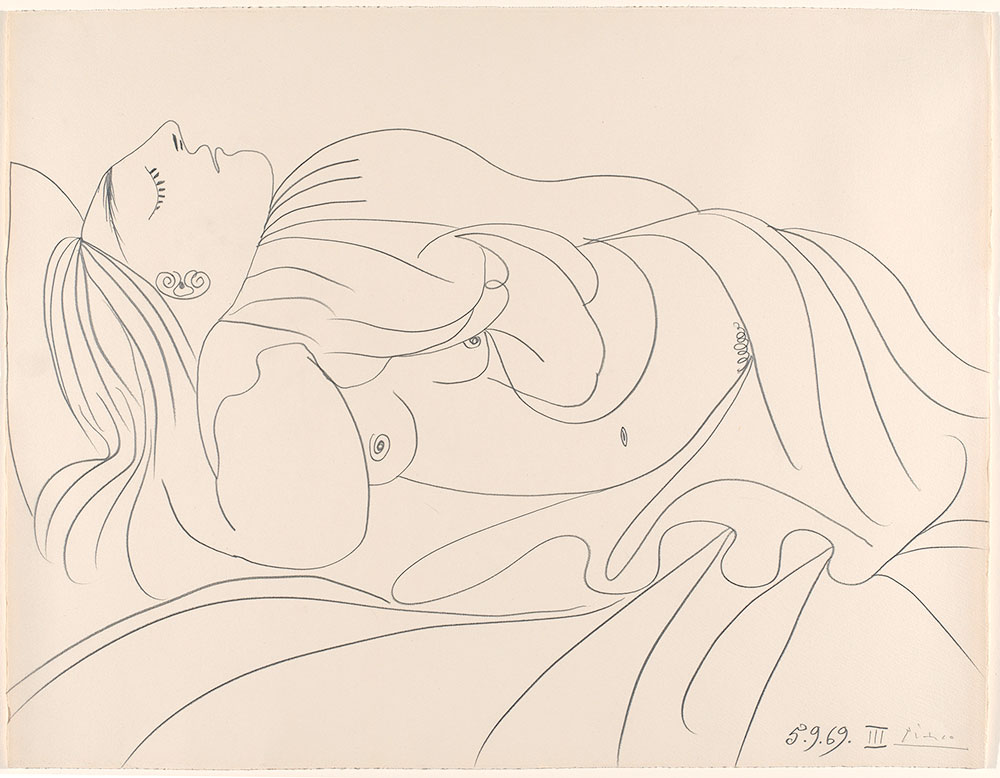

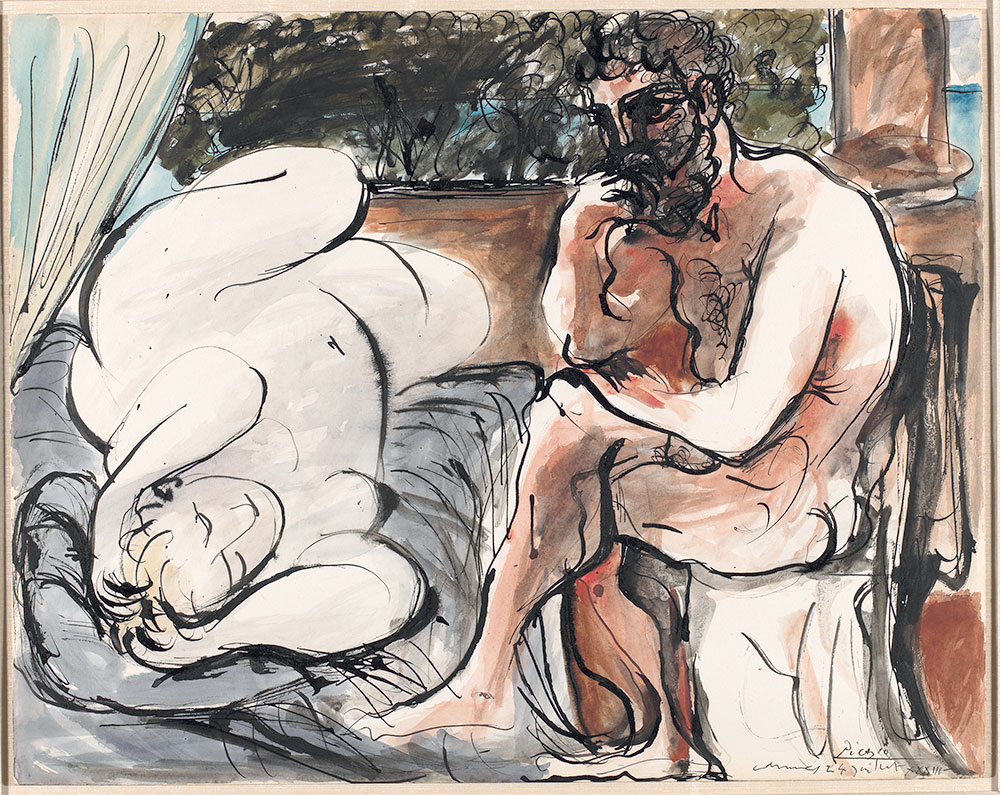

Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso

Spanish, 1881–1973

Reclining Nude (Sleeping Woman), 1969

Graphite

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.857

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

© 2021 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

Henri Matisse

In 1941, while convalescing from a serious illness, Matisse devised a fresh approach to his interest in repeated motifs: a drawing series that he would publish in 1943 as Themes and Variations. Comprising 162 drawings organized into 17 groups, the series mostly depicts female figures reclining or relaxing in chairs. This example is characterized by the contrasts of charcoal and paper and of flatness and depth, as well as by its fluid, energetic line. Other studies in Themes and Variations use a much cleaner line to render their subject. As a whole, the series demonstrates the artist’s commitment to capturing a drawing’s essence through serial reworking.

Henri Matisse

French, 1869–1954

Woman Resting in an Interior, 1941

Charcoal, with stumping

Richard and Mary L. Gray, promised gift to the Morgan Library & Museum

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

© 2021 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

Annibale Carracci

Carracci drew this resting Hercules while preparing a fresco cycle for Cardinal Odoardo Farnese’s private study in the Palazzo Farnese in Rome. The mythical Roman hero is identified by his club, a lion’s hide, and the apple in his right hand. Though lifelike, the figure was not drawn from a live model. Instead, it was inspired by works that Carracci, a recent transplant from Bologna, encountered in Rome, such as an ancient sculpture of the reclining Roman river god Tiber. The drawing is executed on blue paper, which creates a middle tone between the black chalk shadows and white chalk highlights, endowing Hercules with a greater degree of volume and naturalism.

Annibale Carracci

Italian, 1560–1609

Study of Hercules resting, with separate studies of his head and foot, 1595–97

Black chalk, heightened with white chalk, on blue paper, incised

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.838

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

Austėja Mackelaitė: In the Renaissance imagination, Hercules was the epitome of might and masculinity, a demigod born to Jupiter and the mortal Alcmene. He is best known for performing 12 labors as penance for killing his wife and children in a fit of madness. In this preparatory drawing, he is shown in repose, resting his right elbow on the pelt of the Nemean lion that he slew during his first labor. While the hero's face, hair, and beard are rendered in a few soft strokes, Carracci's focus is on his massive musculature, described through carefully blended areas of black chalk touched with white. Note that, at lower right, the artist has sketched Hercules' foot a second time, now significantly enlarged. Just above it appears a ghostly head, possibly another option for the hero's visage in the finished composition.

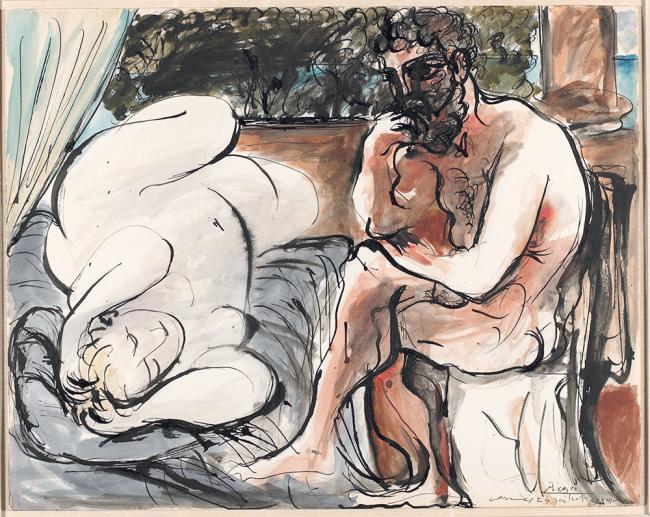

Pablo Picasso

The bearded artist in this drawing is Picasso’s avatar, while the recumbent nude resembles his then-lover, Marie-Thérèse Walter. Watercolor covers much of the sheet, but the model’s body has been left suggestively white, as if to conflate her with the classical statuary that inspired Picasso’s work at the time.

Pablo Picasso

Spanish, 1881–1973

The Artist and Model, 1933

Watercolor and pen and black ink

Richard and Mary L. Gray Art Trust

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

© 2021 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

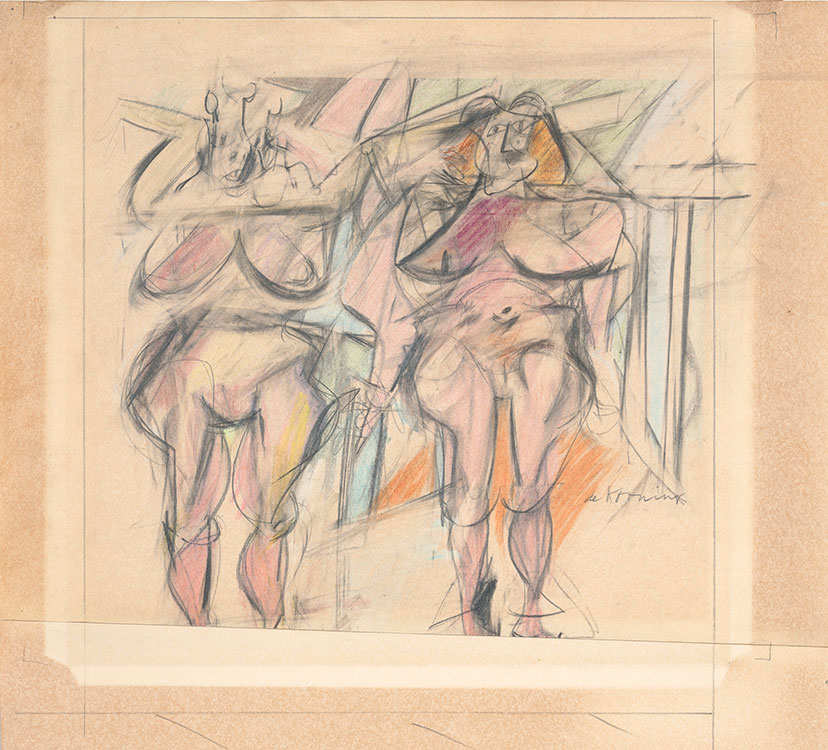

Willem De Kooning

Between 1950 and 1953, de Kooning created a series of paintings and drawings depicting exaggerated, even grotesque, women. In Two Women I, the figures emerge from a field of abstract marks and erasures, underscoring the artist’s dual commitment to abstraction and figuration at a time when Abstract Expressionism was the prevailing artistic movement in the United States. The women are arrayed frontally, one with her arms raised behind her head in likely reference to Picasso’s Les demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). The figures’ large eyes and breasts recall Paleolithic fertility sculptures, attesting to the longevity of the female nude as a subject in art.

Willem De Kooning

American, 1904–1997

Two Women I, 1952

Pastel and charcoal

Richard and Mary L. Gray Art Trust

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

© Willem De Kooning / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

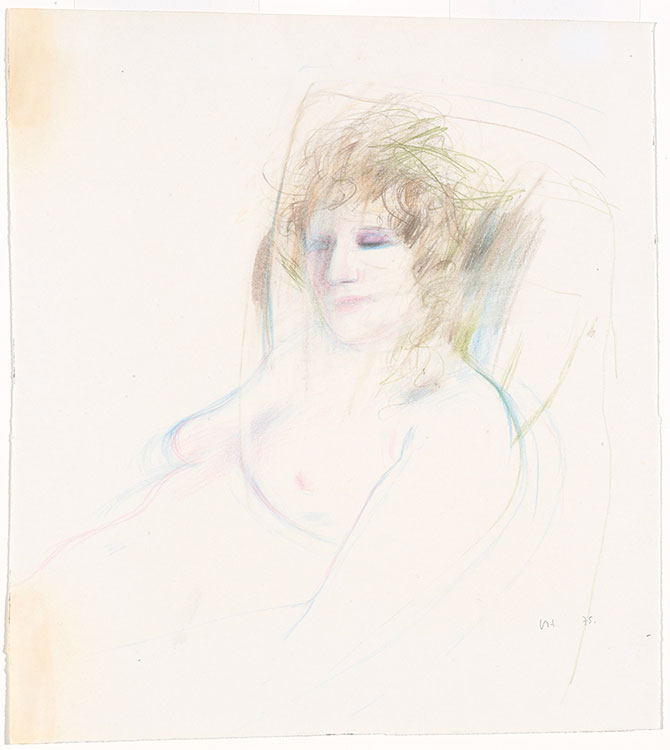

David Hockney

David Hockney

British, b. 1937

Celia, 1975

Colored pencil

Richard and Mary L. Gray, promised gift to the Art Institute of Chicago

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

© David Hockney

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

Rachel Federman: I'm Rachel Federman, Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary drawings at The Morgan. Since the 1960s, Celia Birtwell, pictured here, has been one of David Hockney's most constant muses. This drawing belongs to a group of colored pencil portraits of friends and lovers that Hockney made in the mid-1970s while living in Paris. In contrast to other more finished drawings from this period, this sheet with its visible alterations and smudging has a casual air about it that matches the close and comfortable relationship between sitter and artist. The reclining nude, usually, but not always female, is a perennial subject in the history of Western art. Hockney is an avid student of that history, admiring perhaps above all, the eclectic and influential oeuvre of Picasso, for whom the reclining nude was a major theme. Two such drawings by Picasso are on view nearby. It is instructive to consider both the similarities and the differences in these artists' depictions of their subjects. Although many of Picasso's female subjects, usually lovers, have been identified, Hockney approached Birtwell with a keen attention to the specifics of physiognomy and character that hints at the tenderness of their friendship.

Vincent van Gogh

Van Gogh seems to have been inspired to make this melancholy drawing after reading “Tristement” (Sadly) by the French writer François Coppée, known as “the Poet of the Humble.” The poem describes a mourning widow proceeding along “a very long lane of giant, half- denuded plane trees.” Time has enhanced the drawing’s autumnal mood. The irongall ink that Van Gogh used, once black, has faded to a dark brown and imparted a golden tone to the paper, and the hatched pen lines have bled and merged. The effect overall is a more muted contrast between light and dark.

Vincent van Gogh

Dutch, 1853–1890

Avenue of Pollard Birches and Poplars, 1884

Reed pen and iron-gall ink

Richard and Mary L. Gray, promised gift to the Art Institute of Chicago

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

Georges Seurat

This haunting work belongs to a remarkable body of landscapes that Seurat drew in the early 1880s. A lone figure moves along a path through a park setting with hilly terrain, tended lawns, and tall trees. Seurat applied Conté crayon with varying pressure to the textured paper, creating luminous middle tones counterpoised with solid blacks. With its mysterious, twilit atmosphere, Landscape demonstrates the artist’s unique tenebrist style—characterized by contrasting shadows and dramatic illumination—which he would develop throughout the decade.

Georges Seurat

French, 1859–1891

Landscape, ca. 1881

Black Conté crayon

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.866

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

Rachel Federman: At first glance, the shadowy forms of this landscape seem to emerge from the sheet itself. In fact, they are comprised of countless lines of Conte crayon. Georges Seurat, who is best known as the progenitor of pointillism in which a painting is created from innumerable dots of vivid color, created hundreds of drawings in his short career. They range from early academic nudes, like one seen elsewhere in the exhibition to dark atmospheric drawings like this one. He began these mature drawings on textured paper in 1881 when he was only 22 years old. In this scene of a solitary figure traversing a country path, Seurat placed a familiar subject at the very edge of legibility, teetering on the brink of abstraction. As in his pointillist paintings, he underscored the artifice and mystery of two-dimensional representation. A hundred years after Seurat was born and unencumbered by any fealty to the natural world, the abstract expressionist artist Franz Kline commemorated a trip to Chicago with a drawing nearby, also a study in light and dark. Kline created masses of varying tones by applying individual brushstrokes in different directions. Like Seurat, he enlisted the white of the paper itself as an active element in the composition.

Franz Kline

In the 1940s, Kline developed a distinctive abstract idiom consisting of wide, gestural strokes in black and white. This sheet, titled Chicago in reminiscence of a trip the artist took in 1957, is not a cityscape but a study in contrast and motion. Although the composition is dominated by dense concentrations of black ink, visible brushstrokes denote movement. Kline’s application of white paint—both directly on the paper and over black ink—heightens the sense of opposing forces meeting on the page. Kline once said, “The final test of a painting . . . Is: does the painter’s emotion come across?”

Franz Kline

American, 1910–1962

Chicago, 1959

Brush and black ink, white oil paint, and charcoal

Richard and Mary L. Gray, promised gift to the Art Institute of Chicago

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

© Franz Kline / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photography by Art Institute of Chicago Imaging Department

Giuseppe Porta

An example of Porta’s mature draftsmanship, this drawing demonstrates a range of techniques, from the carefully modeled face and crumpled sleeve pleats to the delicate strokes describing the figure’s beard. The artist achieved rich and vibrant color effects by employing four different chalks against blue-gray paper. The sheet served as a preparatory study for a fresco in the Sala Regia—a formal reception hall in the Vatican—that was executed between 1562 and 1566. The corresponding painted figure, who gestures emphatically while conferring with an armored warrior standing nearby, can be seen in the large crowd at right.

Giuseppe Porta, called Giuseppe Salviati

Italian, ca. 1520–ca. 1575

Bearded man with his right arm raised, 1562–64

Black, red, and ocher chalk, with touches of white chalk, on bluish- gray paper

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.860

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

John Marciari: Hello, I'm John Marciari, the Charles W. Engelhardt curator and head of the Department of Drawings and Prints, and also curatorial chair here at The Morgan. Giuseppe Porta is an artistic chameleon of sorts. He was trained by the Florentine Mannerist artist, Francesco Salviati, and his early work closely resembles that of his master, whose name he also adopted. The two of them traveled to Venice in 1539, but Porto remained behind when Salviati returned to Central Italy. In the years that followed, Porta increasingly came to combine his central Italian sense of form with a Venetian sense of color. His paintings would often model figures and thin glazes of oil paint in the manner of Venetian artists. Similarly, his use of multicolored chalks in a drawing like this one derives from works by the Bassano family, also active in Venice. The Bearded Man, one of the artist's masterpieces, is for a fresco that Porta painted in the Vatican during a brief return to Rome in the 1560s. The figure's face is so full of life that the drawing seems surely based on a live model. But the reason why Porta made so careful a study for a papal guardsman in the middle of a crowded scene remains a mystery, as does the man's identity.

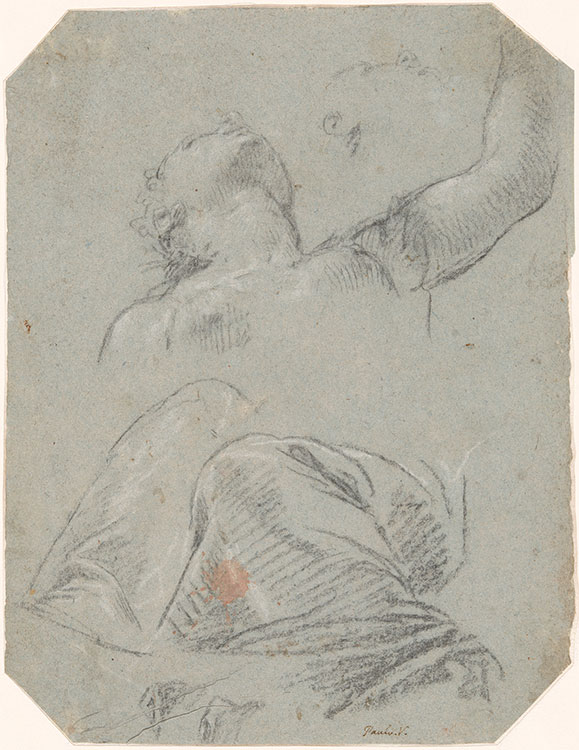

Paolo Veronese

One of Veronese’s first independent commissions in Venice was a very large canvas depicting Saint Mark, the city’s patron saint, crowning female personifications of Christian theological virtues—Faith, Hope, and Charity. This drawing is a preparatory study for the figure of Faith. She is rendered as if seen from below, with her left hand raised and her head turned skyward, creating a powerful impression of upward movement. The study is Veronese’s earliest known drawing in black chalk, which he methodically applied using regular, evenly spaced hatching. Now in the collection of the Louvre, the painting once adorned the ceiling of the Hall of the Compass in the Doge’s Palace in Venice.

Paolo Veronese

Italian, 1528–1588

Study of a seated woman seen from below and another study of her head, 1553–54

Black chalk, with touches of white chalk, on blue paper

Richard and Mary L. Gray, promised gift to the Morgan Library & Museum

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Art Institute of Chicago Imaging Department

Giovanni Battista Naldini

At once strikingly naturalistic and elegantly stylized, this drawing is a brilliant example of Florentine draftsmanship in the late sixteenth century. The carefully posed serpentine figure, whose elongated arms are arranged as if to hold an invisible musical instrument, is probably a studio model or garzone

Giovanni Battista Naldini

Italian, 1535–1591

Study of a seated youth, ca. 1575

Black chalk, with touches of white chalk, squared in red chalk

Richard and Mary L. Gray, promised gift to the Morgan Library & Museum

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

Ian Hicks: I'm Ian Hicks. I'm the Moore Curatorial Fellow at the Morgan Library & Museum. Naldini's immediate and informal study of a seated youth appears to have been made from life, sketched while a young workshop assistant or garzone held the pose. As a young man, Naldini was himself a junior member of a prominent workshop, training under Jacopo Pontormo from 1549 until the master's death in 1556. After a sojourn in Rome, Naldini returned to Florence in 1562 and worked on several important commissions awarded by the Grand Duke of Tuscany and supervised by Giorgio Vasari, whose work hangs elsewhere in this exhibition. In contrast to Giuseppe Salviatti's more elaborate and exacting life drawing of a bearded man nearby, Naldini's study exhibits an economy of means. The initial contours are broadly rendered in black chalk, in places reinforced with more incisive lines. The fall of light is summarily suggested by spare hatching. The result is both distinctive and deeply rooted in a tradition of Florentine draftsmanship. This expressive study is squared in red chalk, indicating that the artist may have intended to transfer the figure into a painted composition, though no such work is known.

Mattia Preti

Born in Calabria in southern Italy, Preti spent his most formative years in Rome and Naples, absorbing artistic influences and developing an exuberant late-Baroque painting style. This drawing, made in preparation for a major altarpiece commission for the Church of Santa Maria dei Sette Dolori in Naples, is one of very few compositional studies by the artist known today. The muscular protagonist bound to a tree by his tormentors is Saint Sebastian, a Roman imperial guard condemned to death for his Christian faith. Although at first glance the saint’s body appears uninjured, a closer look reveals the arrows—faintly rendered in red chalk—piercing his torso and arms.

Mattia Preti

Italian, 1613–1699

Saint Sebastian tied to a tree, ca. 1656

Red chalk, with brush and brown wash

Richard and Mary L. Gray, promised gift to the Morgan Library & Museum

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

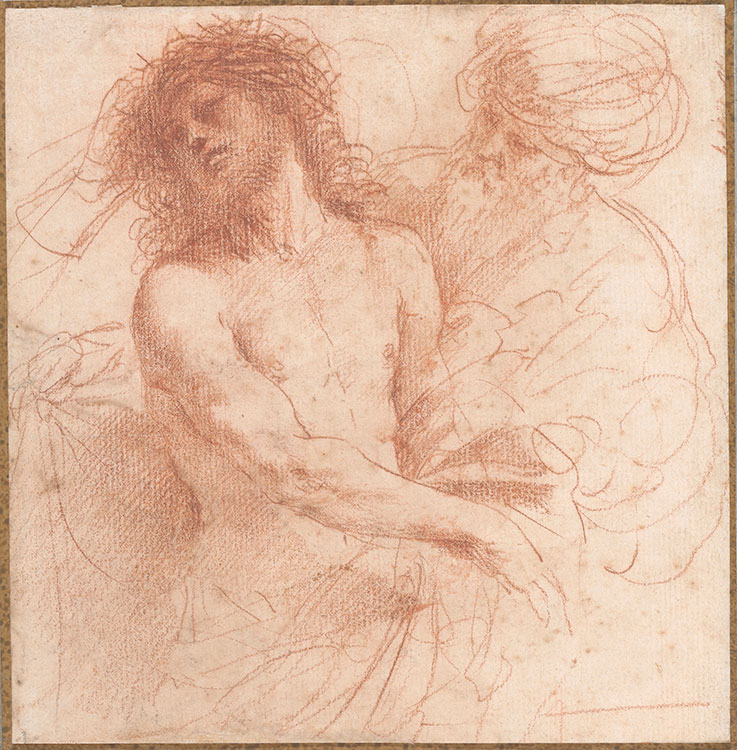

Giovanni Francesco Barberi, called Guercino

Giovanni Francesco Barberi, called Guercino

Italian, 1591–1666

Christ crowned with thorns (Ecce Homo), 1647

Red chalk

Richard and Mary L. Gray, promised gift to the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

Charles LeBrun

Charles LeBrun

French, 1619–1690

Study for a herm, 1674–78

Black chalk, with touches of white chalk, and traces of graphite

Richard and Mary L. Gray, promised gift to the Art Institute of Chicago

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

François Lemoyne

Using only black and white chalk to convey flesh tones, Lemoyne convincingly depicted the hero Hercules in full swing—much like a baseball player at bat. One of two known studies for the figure in Lemoyne’s painting Hercules Clubbing Cacus, this sheet powerfully conveys the artist’s graphic skill. The painting illustrates Hercules’s tenth labor, in which the hero endeavors to bring the monster Geryon’s cattle back to Rome. Upon discovering that the giant Cacus has

François Lemoyne

French, 1688–1737

Hercules raising his club: Study for “Hercules Clubbing Cacus,” 1717

Black and white chalk on buff paper

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.880

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Art Institute of Chicago Imaging Department

Giovanni Francesco Barberi, called Guercino

Produced in the early years of Guercino’s career, this study relates to a now- lost fresco that once adorned the façade of the Palazzo Tanari in Bologna. In contrast to the drawing by Lemoyne on view nearby, here we encounter the mythical hero Hercules pensively leaning on his club, at rest after a battle. His left foot is placed on the Hydra, the multiheaded serpentine monster that he has just defeated. Guercino’s delicate, spidery pen lines have an exploratory quality, while the heavy brown wash is used to convey strong chiaroscuro effects, defining and highlighting individual forms.

Giovanni Francesco Barberi, called Guercino

Italian, 1591–1666

The triumphant Hercules with the vanquished Hydra, ca. 1618

Pen and brown ink, and brush and brown wash, on buff paper

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.879

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Gerbrand van den Eeckhout

Van den Eeckhout was one of Rembrandt’s most successful pupils. This drawing belongs to a group of related studies—some of the most outstanding figure drawings produced in seventeenth-century Holland—characterized by a contemplative mood and an economical rendering. The bearded figure was executed almost entirely with a brush and brown wash applied in broad, energetic strokes. The artist seems to have been particularly interested in describing the stark interplay of light and shade, exemplified by the man’s face. Although the figure was probably not observed from life, he has an intense, brooding presence.

Gerbrand van den Eeckhout

Dutch, 1621–1674

A bearded figure wearing a turban and fur coat, half length, turned to the right, ca. 1670

Brush and brown wash, and pen and brown ink

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.845

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Art Institute of Chicago Imaging Department

Austėja Mackelaitė: Gerbrand van den Eeckhout was a prolific draftsman with over 200 studies attributed to him today. From around 1635 to 1640, he spent time in Rembrandt's Amsterdam studio, absorbing the older artist's lively and endlessly inventive approach to drawing. While some of Rembrandt's students never fully escaped the influence of their master, van den Eeckhout developed a style that was entirely his own. This drawing is a case in point. Look closely at the rapid painterly marks that describe the man's attire, or at the way in which light catches in his wavy shoulder-length hair. The unmistakably modern sensibility of this and other sheets by van den Eeckhout have long baffled scholars. Executed almost entirely in brush and brown wash, these works have been attributed to a wide range of 17th century artists, such as the genre painter, Johannes Vermeer, and even to 18th century French masters like Fragonard. Indeed, one might argue that van den Eeckhout's unmatched facility with the wash aligns the sheet more closely with Italian Baroque drawings, such as the study by Giorgino displayed nearby, than with works by his northern contemporaries. The enigmatic quality of the work is heightened by the man's sullen countenance and the sharp contrast between light and dark.

Georges Seurat

Georges Seurat

French, 1859–1891

Academic Male Nude, 1877

Black Conté crayon, black chalk, and charcoal The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.865

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

Francesco de' Rossi, called Francesco Salviati

Salviati’s many surviving drawings reflect his fecund imagination, technical proficiency, and stylistic flair. This sheet is notable for its skillful application of brown wash, including thick strokes, quick accents, and sinuous contours. The artist’s bravura graphic performance is matched by his playful interpretation of the subject: a soldier in a quasiballetic pose. The young man balances on one foot while gingerly lifting a curtain, whose volume and heft Salviati has conveyed through masterfully modulated brown wash. Unconnected to any of the artist’s known projects, this large, highly finished drawing was likely intended to function as an independent work of art.

Francesco de' Rossi, called Francesco Salviati

Italian, 1510–1563

Young warrior, seen from behind, lifting a curtain, 1550–55

Pen and brown ink, and brush and brown wash, heightened with white opaque watercolor, over black chalk

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.864

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

Paul Cézanne

In the 1870s, Cézanne took up the subject of bathers, an interest that persisted until the end of his career. The artist did not use live models. His impetus was more conceptual than naturalistic, and he approached figure study above all as an exercise in formal composition. This drawing comes from a group of studies and paintings that feature a single male bather with one arm rigidly outstretched. The figure’s unconventional pose was inspired by an ancient Roman sculpture of a dancing satyr in the Louvre. Cézanne’s staccato lines, while seemingly quick and spontaneous, were in fact applied carefully and methodically as he slowly explored his subject, endowing his bather with a monumentality that belies the drawing’s modest dimensions.

Paul Cézanne

French, 1839–1906

Bather with Outstretched Arms, 1874–77

Graphite on pieced paper

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.840

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

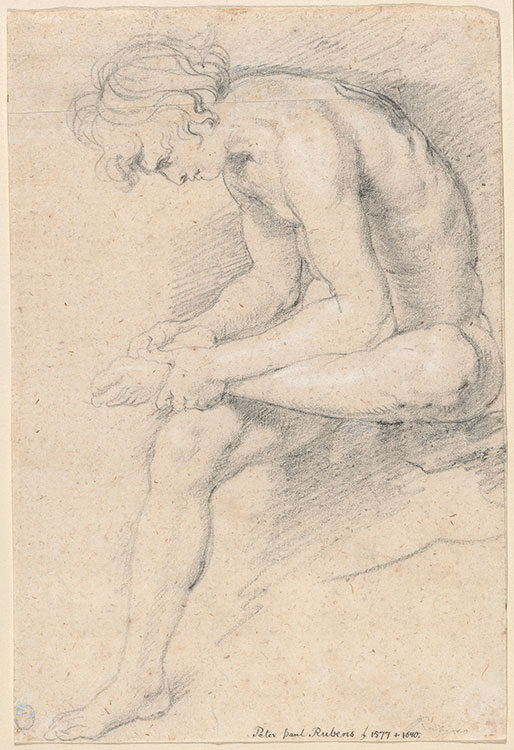

Peter Paul Rubens

Ancient sculpture, which Rubens studied during histwo stays in Rome, significantly shaped his artisticpractice. He believed that to achieve mastery of painting, it was crucial to understand ancient art, and “to be so thoroughly possessed of this knowledge that it may diffuse itself everywhere.” In this drawing, Rubens arranged a studio model in a pose derived from the Hellenistic bronze known as the Spinario, which shows a boy removing a thorn from the sole of his foot. Closely following an ancient example yet based on a live model, the drawing demonstrates Rubens’s conviction that art should respond to older works but ultimately imitate nature.

Peter Paul Rubens

Flemish, 1577–1640

Nude youth in the pose of the Spinario, ca. 1610–16

Black chalk with white chalk

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.863

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

Austėja Mackelaitė: The importance of ancient sculpture in Rubens' development and artistic practice is difficult to overstate. He visited Rome twice and each time returned to his native Antwerp with a large cache of drawings recording the monuments and sculptures he encountered there. Having acquired considerable wealth through his artistic and diplomatic activities, Rubens even started collecting antiquities himself, amassing one of the most important collections of ancient marbles in 17th century Flanders. Nonetheless, Rubens was also aware of the dangers posed by the overzealous study of ancient art and insisted that drawings after antiquities must not be static or inert, that they must not, in his words, smell of stone. This sheet, which was made not long after Rubens' return from Rome encapsulates this idea. The artist arranged a young male model in a position derived from the Spinario, an ancient bronze statue, which he must have seen in Rome. By focusing on a live model, he transformed the classical image into a living, breathing presence. The artist employed soft, tightly packed strokes of black chalk to render the youth's anatomy and relied on unworked paper to convey the translucency of his skin. Working nearly three centuries later, Paul Cézanne also investigated the human form with the help of classical statuary. The peculiar pose of the bather, with outstretched arms exhibited nearby, was derived from a Roman sculpture of a dancing satyr. Unlike Rubens however, Cézanne was unconcerned with naturalism. His primary interest laid in drawing after antiquity as an exercise in formal composition.

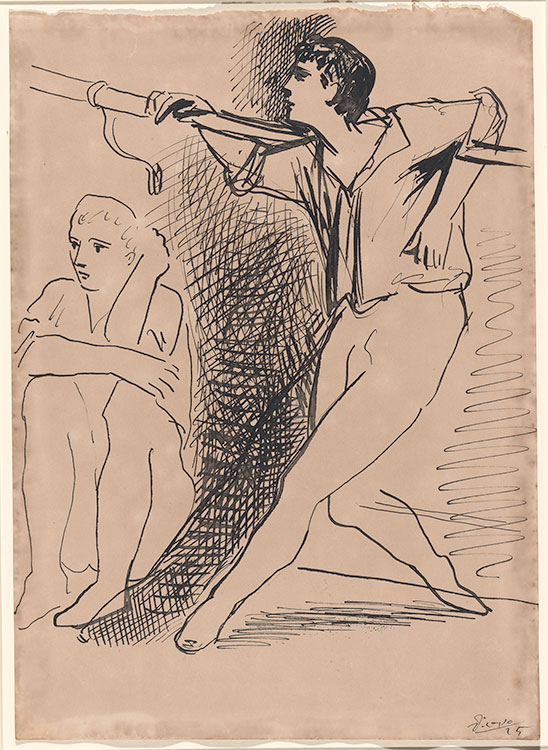

Pablo Picasso

Picasso created this drawing while observing rehearsals of the Ballets Russes in Monte Carlo. His association with the itinerant ballet company began in 1917, when he designed sets and costumes for Parade. Represented in abbreviated yet remarkably descriptive lines, the languorous dark- haired dancer at the barre has been identified as Serge Lifar, while the seated blond man is probably a Ukrainian dancer known as Khoer. Picasso concealed an earlier version of Lifar’s right leg with extensive crosshatching between the two figures.

Pablo Picasso

Spanish, 1881–1973

Two Dancers, 1925

Pen and black ink

Richard and Mary L. Gray, promised gift to the Morgan Library & Museum

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

© 2021 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

Pablo Picasso

In the final months of 1906, Picasso made several studies of female nudes with deeply cut, almondshaped eyes and ovoid heads. The drawings were inspired by ancient Spanish (Iberian) sculptures that he had seen in the Louvre in Paris, and they reflect the artist’s attempt to transcend the traditional academic nude in his search for a more archetypal form. In this example, Picasso rapidly sketched his figure full-length and frontally, also including a study of her head in profile. The choppy, staccato graphic language was influenced by Paul Cézanne, whom Picasso called his “one and only master” (see Cézanne’s Bather with Outstretched Arms elsewhere in the exhibition).

Pablo Picasso

Spanish, 1881–1973 Female Nude, 1906

Chalk, with graphite

Gray Family Collection

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

© 2021 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

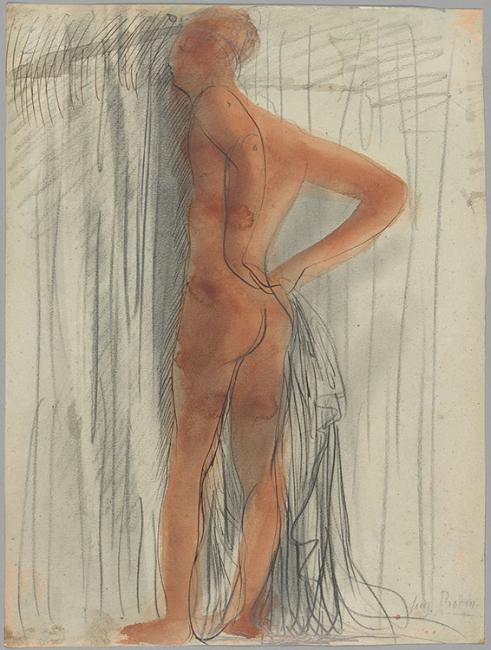

Auguste Rodin

Rodin was a prolific draftsman who, especially in his later years, made thousands of drawings of nude models in his studio. Energetic and fluid, they record unexpected poses and unusual viewpoints that depart from established European art- historical precedents. A contemporary described Rodin’s method: “Equipped with a sheet of paper . . . And a graphite pencil . . . He gets his model to strike a more or less unstable pose, then draws quickly without taking his eyes off the model. The hand roams haphazardly, the pencil often runs off the page. . . . Not once does [he] look at it. This snapshot of movement is taken in less than a minute.”

Auguste Rodin

French, 1840–1917

Nude Woman Standing, Seen from the Back with Her Hands on Her Hips, 1898–1900

Graphite, watercolor, and pen and black ink, on paper prepared with a light- blue wash

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.862

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Art Institute of Chicago Imaging Department

Jennifer Tonkovich: I'm Jennifer Tonkovich, the Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator of drawings and prints here at the Morgan Library & Museum. We often imagine an artist sitting with a pad balanced on his knees or at an easel, drawing a model who holds a still pose at the center of a room. This was not Rodin's practice. By the 1890s, he was successful enough to employ female models on a regular basis and had them wander around his studio as he produced rapid gestural drawings capturing the movement of their bodies. He was not interested in creating an illusion of 3-dimensionality or describing the body with anatomical accuracy. Instead, he sought to capture the expressive potential of the body in its natural state. He employed graphite and thin fluid washes, materials that move quickly across the page and lend themselves to describing the supple contours of the body. Rodin like Degas, in the drawing of two dancers at the entrance to this gallery, embraced awkward poses and unguarded everyday movements. Although he worked as a sculptor, his drawings of the body are essential to his work, not in a preparatory sense, but in an exploratory one. The juxtaposition of this figure study with Picasso's robust drawing of a woman, which also investigates the female body, reveals the Spanish artist's greater interest in the expressive potential of the woman's head. An element that rarely captured Rodin's attention.

Jim Dine

Jim Dine

American, b. 1935

Thin Red Lips, 2008

Charcoal and pastel

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.844

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

© Jim Dine / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

Jean-Baptiste Isabey

Jean-Baptiste Isabey

French, 1767–1855

Portrait of the Artist Joseph Chinard, 1799–1802

Black chalk, with stumping, and touches of brush and black watercolor, heightened with white opaque watercolor

Richard and Mary L. Gray, promised gift to the Art Institute of Chicago

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

Jean Dubuffet

Dubuffet sought to replicate the immediacy of the art of the untutored. In this sheet, he incised four figures into a ground of opaque watercolor, exposing the sandpaper he used as a support. The technique shares more with graffiti and the scrawls of children than with academic drawing. The artist once remarked, “When I say draw I’m not to the slightest degree thinking of faithfully reproducing objects . . . . No, it’s a matter of something quite different: to animate the paper, to make it palpitate.”

Jean Dubuffet

French, 1901–1985

Four Figures, 1946

Opaque watercolor, with incising, on coarse sandpaper

Richard and Mary L. Gray, promised gift to the Morgan Library & Museum

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

Francesco Bonsignori

This moving portrait of an older man was made in northern Italy, probably in the 1490s. The man’s pensive gaze suggests an introspective mood. His unshaven chin, wrinkled flesh, sunken cheeks and eyes, and thinning hair are rendered attentively, with uncompromising naturalism—evidence of the artist’s earnest inquiry into the aging process. The skillful application of charcoal—which ranges from bold, velvety lines to very light hatches, blended with a stump and brush—creates a convincing impression of plasticity and volume.

Attributed to Francesco Bonsignori

Italian, ca. 1455–1519

Portrait of an old man, late fifteenth century

Charcoal, with wet brush and stumping, on tan paper prepared with a gray ground

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.834

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

Ian Hicks: The author of this sensitive portrait remains open to question. Scholars generally agree that it dates from the late 15th century, but different artists or artistic circles have been proposed. Most recently, an attribution to Francesco Bonsignori has been advanced. The most gifted member of an artistic family, Bonsignori spent his early career working in his native Verona before relocating to Mantua in 1492 to work at the Gonzaga Court. In forging his artistic identity, the artist drew inspiration from Giovanni Bellini and Andrea Mantegna, among others. To complicate matters, the comparable study behind this drawing's attribution to Bonsignori has itself oscillated under these different names. Attributional questions aside, the drawing is remarkable for its attentive descriptions of texture, particularly the sitter's creased and folded skin, and his wispy hair and beard. The artist was concerned with describing the play of light over the compelling topography of the man's face. The drawing's detailed characterization and unmediated naturalism strongly suggest that the artist made this study directly in front of the kindly sitter. There is nothing in this portrait to indicate the grandeur of courtly status, and the artist may have made it on his own initiative, like the nearby study by Honoré Daumier.

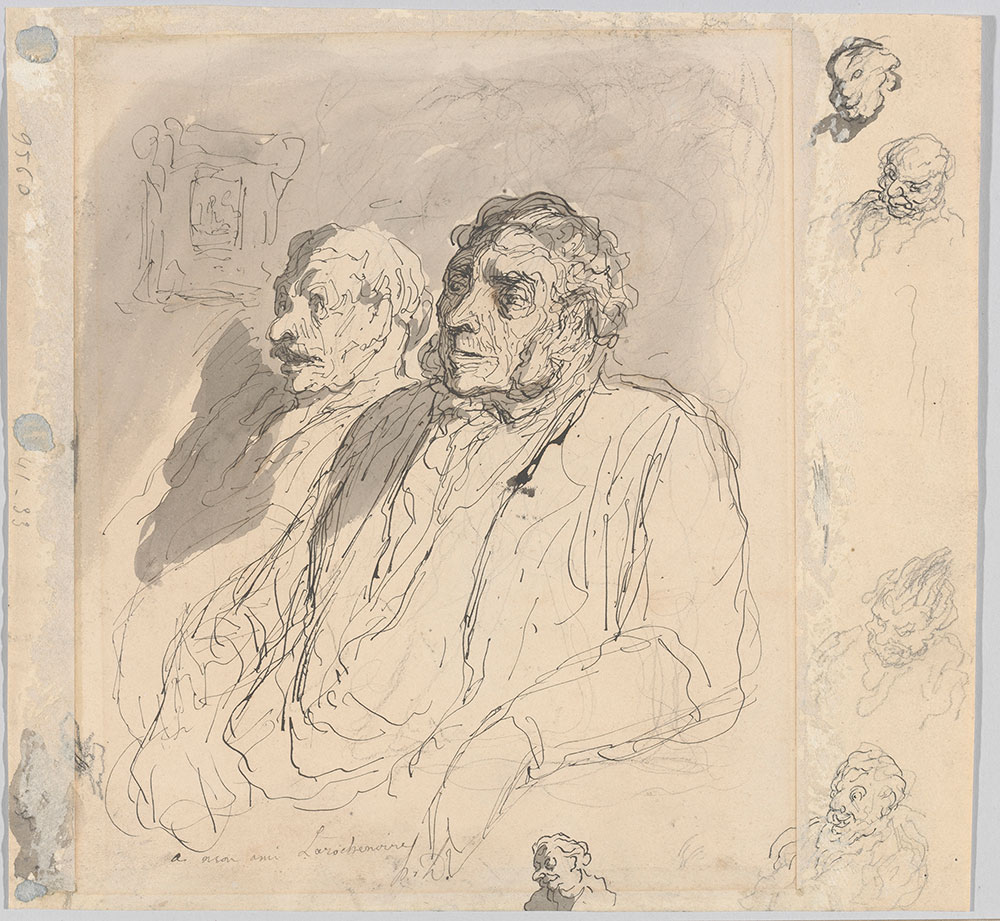

Honoré Daumier

Daumier’s wiry pen-and-ink lines aptly, and mercilessly, describe the creases on his subjects’ weary faces. This sheet appears to relate to a series of watercolors featuring bourgeois gentlemen that the artist produced for sale to collectors in the 1860s, after he was temporarily let go from the satirical French daily Le Charivari. Daumier drew constantly, often adding faces in the margins of sheets as he did here. The face to the right of the inscription at bottom is thought to represent the artist himself.

Honoré Daumier

French, 1808–1879

Study of Two Men (Spectators), 1863–65

Pen and black ink, brush and wash, and graphite, over black chalk

Richard and Mary L. Gray, promised gift to the Morgan Library & Museum

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

Lelio Orsi

The heroic sun god Apollo drives his four- horse chariot while Aurora, goddess of the dawn, strews flowers in his path, announcing his—and the new day’s—arrival. Orsi’s drawing is a final preparatory sketch for an illusionistic fresco (now lost) that once adorned the clock tower in the northern Italian city of Reggio Emilia. Orsi was so successful in suggesting the god’s powerful forward motion that Apollo looks as if he might fly from his chariot and out of the picture frame. The design was meant to be seen from below, which explains the slightly distorted perspective.

Lelio Orsi

Italian, 1511–1587

Apollo driving the chariot of the sun, ca. 1544–45

Pen and black ink, with brush and brown wash, heightened with white opaque watercolor, with incising, on paper prepared with a light- brown wash

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.855

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Art Institute of Chicago Imaging Department

Ian Hicks: Many of the most important commissions by the historically obscure artist Lelio Orsi, were outdoor facade frescoes, which had been lost to time. But his highly individual style is still known from his powerful surviving drawings. Like many other Emilian artists, Orsi was profoundly influenced by Correggio, but he had eclectic tastes that included a deep interest in the muscular figures of Michelangelo. This impressive drawing is among the relatively rare fixed points in Orsi's corpus as it is connected to a commission he received in 1544 to fresco the clock tower in the town of Reggio Emilia. Appropriate to the location, the design depicts Apollo driving his chariot, which is carried aloft by four charging horses. In the foreground, Aurora, or Dawn, stands on a cloud announcing the first rays of the new rising sun. Fragmentary zodiacal symbols of the summer and autumn months appear in the background. The artist delineated the dramatically charged poses of Apollo and his horses with a virtuosic contrast of white heightening against a brown wash preparation. Likewise, Ludovico Carracci's nearby drawing employs this same technique and similarly excited figures to evoke the drama of divine revelation.

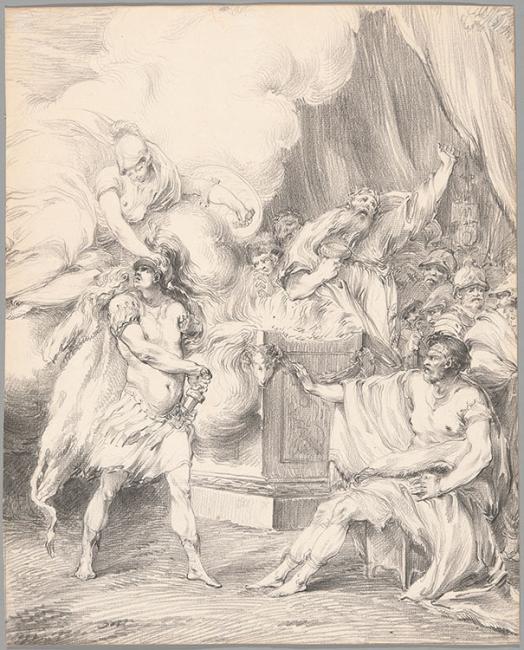

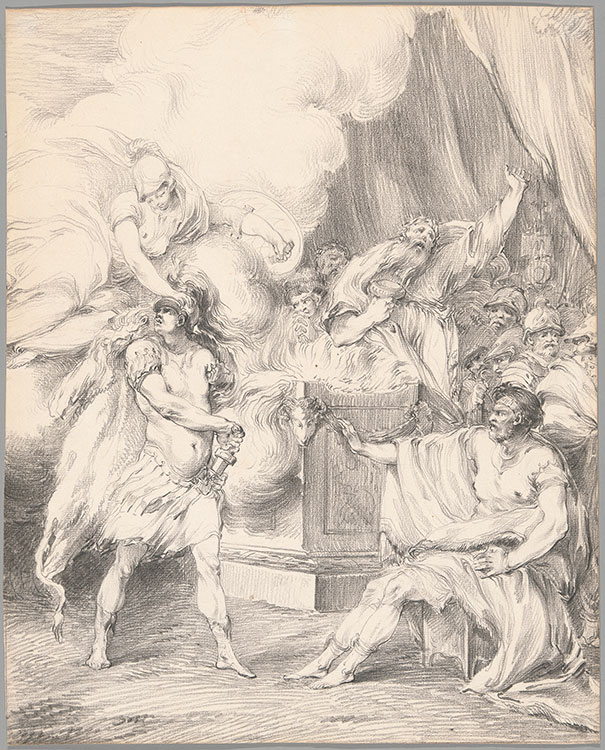

Lodovico Carracci

As narrated in the New Testament, Saul of Tarsus, a ruthless persecutor of Christians, was struck from his horse by the blinding light of a divine apparition on his way from Jerusalem to Damascus. In this large, elaborate study for an altarpiece in the Basilica di San Francesco in Bologna, Lodovico emphasized the centrifugal drama of the event by crowding the picture plane with a seething mass of human and equine forms. The artist’s bold, painterly technique—combining pen and ink, washes, and white oil paint—allowed him to achieve the spectacular contrasts of light and dark that often characterize his paintings.

Lodovico Carracci

Italian, 1555–1619

The conversion of Saint Paul, 1587–89

Pen and brown ink, with brush and brown wash, heightened with white oil paint, over traces of black chalk, on paper prepared with a brown oil wash

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.839

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

Benedetto Luti

The election of Oddone Colonna as Pope Martin V in 1417 ended the Western Schism, during which multiple parties had claimed the papal title. In this drawing, Colonna is depicted receiving the keys of Saint Peter—the traditional symbol of papal authority—from a female figure kneeling before him. To her right, the figure riding a lion and holding a column personifies the Colonna family, whose coat of arms featured a column (colonna in Italian). Highly theatrical and emotionally expressive, the drawing epitomizes late-Baroque virtuoso design and draftsmanship.

Benedetto Luti

Italian, 1666–1724

Allegory of the elevation of Cardinal Deacon Oddone Colonna to the papal chair as Pope Martin V, 1700

Pen and brown ink, and brush and brown wash, over black and red chalk, heightened with white opaque watercolor

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.882

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Art Institute of Chicago Imaging Department

Attributed to Simon Vouet

Born into a family of Parisian painters, Vouet spent his early career in Rome working for aristocratic and ecclesiastical patrons. Although he was involved in many painting commissions during those years, few drawings seem to have survived; Kneeling angel may be one of his rare Roman sheets. The robust yet elegant angel is characteristic of Vouet’s early style, with its combination of black and white chalk and the careful description of light and shadow on the drapery folds. The study relates to a chapel vault decoration, featuring musical angels, that the artist painted in the Roman church of San Lorenzo in Lucina.

Attributed to Simon Vouet

French, 1590–1649

Kneeling angel, 1623–24

Black chalk, heightened with white chalk, on blue paper, squared in red chalk

Richard and Mary L. Gray, promised gift to the Morgan Library & Museum

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

John Marciari: Simon Vouet was born in Paris, but he spent 15 formative years in Italy as a young artist. When he returned home in 1627, he had a revolutionary effect on French painting. Introducing the Baroque style of Caravaggio and the Carracci, training an entire generation of French artists, and becoming the favorite painter of Cardinal Richelieu and King Louis XIII. Vouet's influence extended into the field of draftsmanship, and it's hard to imagine the drawings of Charles Le Brun or Francois Lemoyne seen elsewhere in this exhibition without Vouet's example. Yet, despite the many paintings that survive from Vouet's important time in Italy, there are only a handful of drawings from his Roman years, with this one the most recent discovery. The Kneeling Angel, is a study for a frescoed vault that Vouet painted in the Church of San Lorenzo in Lucina in Rome. A curious feature of the sheet, however, is the lightly sketched face at right. A second figure is present in this location in the fresco, but he does not look like the man in the drawing. Perhaps, while making a study of the angel, Vouet remembered that he had to plan for a second figure there and drew a quick portrait sketch of someone sitting in his studio.

Peter Paul Rubens

A prolific designer of book illustrations, Rubens considered such work a relaxing activity for Sundays and religious holidays, as a break from his painting commissions and diplomatic duties. He drew this preparatory study for an engraving that would accompany a 1614 edition of the Breviarium Romanum (Roman Breviary), a liturgical book used by Catholic clergy during Mass. In Rubens’s unusual interpretation of the Last Supper scene, a dignified Christ appears in profile and at the side of the composition. Of the twelve disciples in his company, the treacherous Judas has been placed most prominently at center. The verticality of the image, chosen to accommodate the book’s dimensions, gives the impression of a lofty interior, with the assembled figures compressed in the lower half of the sheet.

Peter Paul Rubens

Flemish, 1577–1640

The Last Supper, 1613–14

Pen and brown ink, with brush and brown wash, heightened with touches of white opaque watercolor, over traces of black chalk, incised

Richard and Mary L. Gray, promised gift to the Art Institute of Chicago

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

This sheet is a study for an unrealized painting commissioned by Charles Marcotte, Rome’s inspector general of waterways and forests and a great friend of Ingres’s. It depicts Santa Maria Maggiore’s Borghese (Pauline) Chapel, viewed from the church’s nave, during a devotional rite called the Quarantore that involves forty hours of continuous prayer. Although figures are scattered throughout the composition, the artist imbued the scene with a sense of calm and stillness, emphasizing architectural symmetry and the interplay of light and shadow.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

French, 1780–1867

The Borghese Chapel in Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome, 1824

Pen and brown ink, graphite, and brush and gray and brown wash, with red and ocher opaque watercolor, heightened with white opaque watercolor

Richard and Mary L. Gray, promised gift to the Art Institute of Chicago

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

French, 1780–1867

Portrait of a Young Woman, 1812

Graphite

Richard and Mary L. Gray, promised gift to the Art Institute of Chicago

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Art Institute of Chicago Imaging Department

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

One of Ingres’s largest and most ambitious portrait drawings, this work depicts the Parisian society hostess, writer, and critic the Comtesse Marie d’Agoult and her daughter Claire. Ingres typically produced his portrait drawings without preparation and in a single sitting. This work, in contrast, required at least two sittings and three preparatory studies. The drawing is notable for its evocation of the richly furnished interior of d’Agoult’s home. The artist selectively applied yellow watercolor to enhance objects and added white heightening to the sitters’ dresses to suggest the sheen of silk.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

French, 1780–1867

Comtesse Charles d’Agoult (Born Marie de Flavigny) and Her Daughter Claire d’Agoult, 1849

Graphite, heightened with white opaque watercolor, with touches of yellow watercolor

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.852

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Art Institute of Chicago Imaging Department

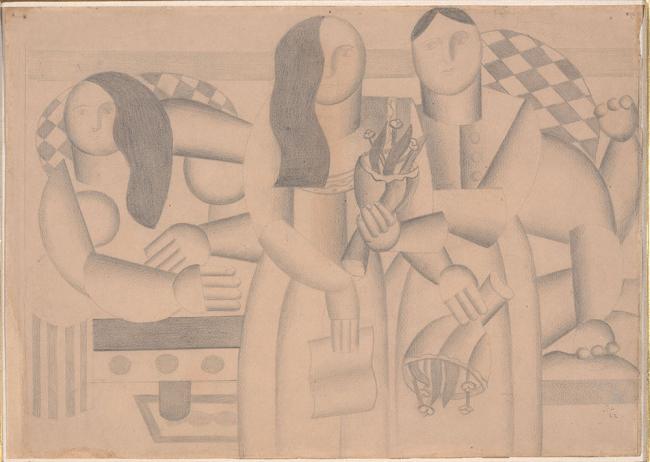

Jennifer Tonkovich: Ingres was seen by his contemporaries as Raphael's heir for his graceful manner, an aspect of his style particularly evident in his drawings. His precise manner of wielding his pencil set a standard for graphite drawing that dominated the 19th century and remained a source of inspiration and challenge for modern artists, from Picasso to de Kooning and Hockney. Ingres was meticulous in his approach to the carefully composed portrait of Madame d’Agoult and her daughter. Notice the plants in the background and the reflections in the mirror above the mantle. The artist was 69 years old when he produced this complex dual portrait. It can be seen in contrast to the swiftly-executed portraits of his youth, which generated an essential income stream for the emerging artist. Such portraits feature a fashionably-dressed figure shown three quarters length on a blank page. For this mature study, he lingered longer, artfully situating the full-length seated forms of the women in a detailed interior. The elegant formal arrangement of Ingres's portrait is not that different from Leger's use of mechanized women's bodies as design elements. Both artists reveled in the formal structure in which bodies, furniture, and architecture are treated in a consistent manner. In both sheets, the severe linearity is modulated by the women's accoutrements, Leger's bouquets and Ingres's rustling silks. What strikes me most about the portrait of Madame d’Agoult and her daughter, alongside the Leger, is the emphasis that both artists have placed on the dark, curvilinear swaths of the women's hair, introducing a soft, pliable element into a crystalline atmosphere.

Fernand Léger

Léger exemplified the “return to order,” the classicizing impulse that emerged in the arts after World War I. In his paintings and drawings, he simultaneously looked back to the harmony of classicism—as embodied in the drawings of Jean- Auguste- Dominique Ingres—and forward to the technological progress and rationalism promised by the industrial order. Even his human subjects, as seen here, take on the appearance of machines. The three women have perfectly spherical heads and breasts and cylindrical necks, while their skirts suggest the fluting of classical columns.

Fernand Léger

French, 1881–1955

Composition/Three Women, 1922

Graphite

Richard and Mary L. Gray, promised gift to the Art Institute of Chicago

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

© Fernand Léger / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

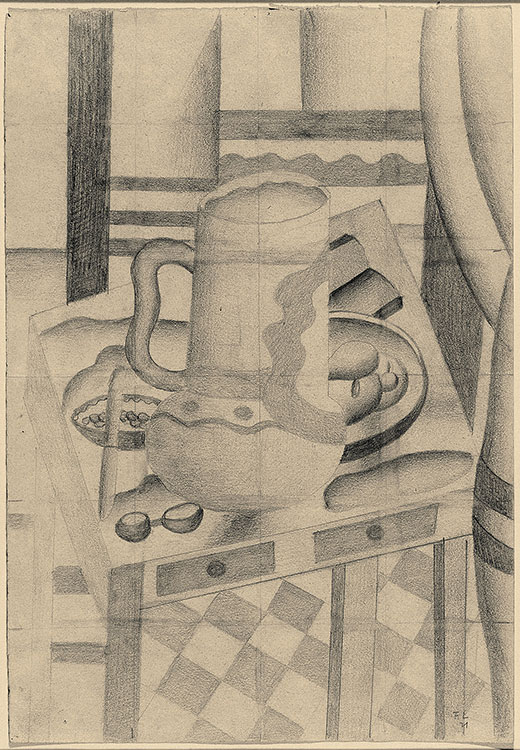

Fernand Léger

Fernand Léger

French, 1881–1955

Still Life with Tankard, 1921

Graphite

Richard and Mary L. Gray, promised gift to the Morgan Library & Museum

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

© Fernand Léger / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

Jennifer Tonkovich: This drawing participates in the long tradition of still life, but it also embodies Fernand Léger's aspirations as a painter of modern life. He once wrote, "The beautiful is everywhere, perhaps more in the arrangement of your saucepans on the white walls of your kitchen than in your 18th century living room or in the official museums." Rejecting the art of the Italian Renaissance, which he perceived as imitative rather than innovative, Léger preferred works of popular and ancient art, as well as the art of certain French masters, including Ingres and Cézanne. In this sheet, squared for transfer to a canvas, a common beer mug sits on a tabletop that is tipped forward in the manner of a Cézanne still life. The subject is particularly notable in light of Léger's valorization of the French working class. Wary of the excesses of commercial capitalism, Léger sought in his art to situate objects of mass consumption, which possess a beauty of their own, within balanced and harmonious compositions. Here, patterns drawn on the surface of the mug echo the curves of the vessel itself, as well as other objects on the table. The drapery to the right possesses the regularity of a mechanically produced object, while the checkered kitchen floor is treated as pure pattern, tipped up so that it is nearly parallel to the picture plane.

Fernand Léger

Fernand Léger

French, 1881–1955

Mechanical Forms, 1923

Graphite and white opaque watercolor

Richard and Mary L. Gray, promised gift to the Art Institute of Chicago

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

© Fernand Léger / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

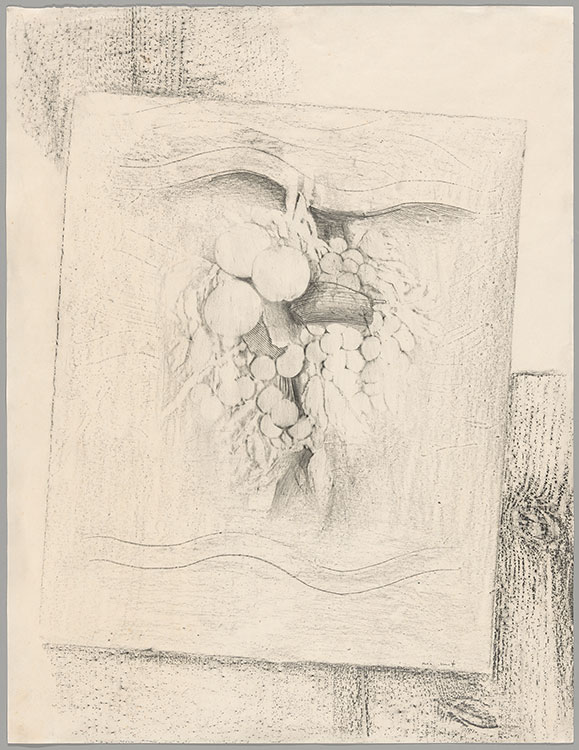

Max Ernst

This sheet is an example of frottage, a method of creating a design by rubbing pencil over paper laid on a textured surface. By using this technique, Ernst surrendered some control, thus expanding the possibilities of his art. The border of Fruits, with its softly rendered wood grain pattern, is a classic example of the method. The central still life, however—turned on its axis and appearing to float in space—has a compositional clarity that is difficult to achieve with frottage.

Max Ernst

German, 1891–1976

Fruits, 1925

Black colored pencil or crayon frottage

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.846

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

© Max Ernst / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photography by Art Institute of Chicago Imaging Department

Giorgio Vasari

With quick, spidery lines in pen and ink, Vasari vivified Saint Paul’s heavenly vision of Christ on the road to Damascus. The artist’s approach to the biblical scene—particularly the close- cropped, horizontal format—differs notably from that of Lodovico Carracci, whose Conversion of Saint Paul appears elsewhere in the exhibition. This sketchwas a preparatory drawing for one of three frescoes that Vasari designed for a church ceiling vault in the central Italian town of Cortona. The paint stainson the right- hand side suggest that the drawing was used during the painting process.

Giorgio Vasari

Italian, 1511–1574

The conversion of Saint Paul, 1554

Pen and brown ink, and brush and brown wash, with splatters of gray, green, and pink paint, over black chalk, squared in black chalk

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.872

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Art Institute of Chicago Imaging Department

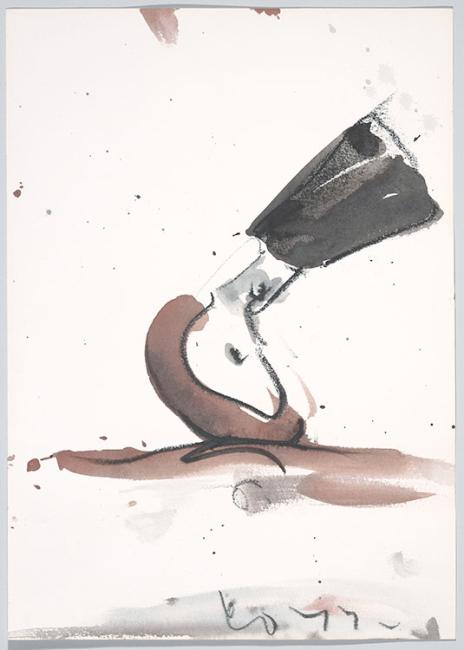

Austėja Mackelaitė: Ink stains and paint splotches, which are special and noticeable at the right side of the composition, are essential to understanding the function of this drawing in Vasari's workshop. Far from a precious sheet, this was a working drawing, which the artist made in preparation for a fresco with a conversion of St. Paul commissioned by the Jesuit church in Cortona. The paint stains indicate that Vasari might have used the sheet during the actual painting process. The drawing is squared in black chalk, which would have helped the artist transfer his composition to a large scale fresco. While the stains on Vasari's sheet are incidental, the splotches on Claes Oldenburg's drawing nearby are integral to the work. In this depiction of the Typewriter Eraser, one of the key visual subjects, which the artist explored over the course of his career Oldenburg's loose, gestural, truly virtuosic approach to watercolor transforms this humble everyday object into a lively and expressive form.

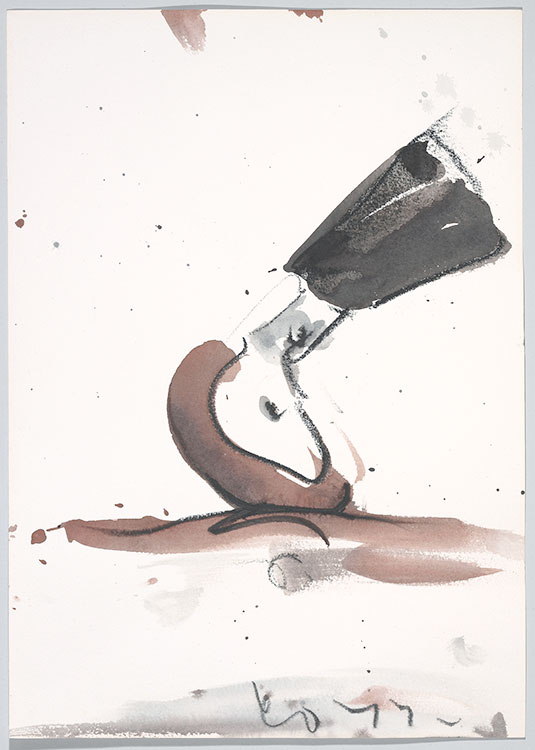

Claes Oldenburg

Many of Oldenburg’s motifs come from childhood interests. The typewriter eraser is one such example, recalling a period when he played at being a journalist in his father’s home office. The subject is also in keeping with his general attraction to ordinary household items and consumer products. Oldenburg first introduced the typewriter eraser into his work in 1970, and it continued to inspire drawings, prints, and sculptures for nearly three decades. In this sheet, the artist animated—and even anthropomorphized—his humble subject with lively, seemingly spontaneous marks.

Claes Oldenburg

American, b. 1929

Typewriter Eraser, 1977

Crayon and watercolor

Gray Family Collection

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

© Claes Oldenburg

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo

Amid a wooded landscape strewn with ancient monuments and human and animal skulls, two men and a youth ponder the state of the world. The men are Democritus and Heraclitus, ancient Greek thinkers who represent opposing temperaments and philosophical perspectives. Democritus, “the Laughing Philosopher,” found amusement in human follies, while Heraclitus was a loner and misanthrope, earning the epithet “the Weeping Philosopher.” Tiepolo created this luminous scene by layering brown washes of different intensities and leaving areas of paper untouched to serve as highlights.

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo

Italian, 1696–1770

Democritus and Heraclitus laughing and sorrowing over the follies of the world, 1742–43

Black chalk, with pen and black and brown ink, and brush and brown washes, heightened with white opaque watercolor

Richard and Mary L. Gray, promised gift to the Art Institute of Chicago

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo

Between 1797 and his death in 1804, Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo—the son of Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, whose work is on view nearby—created 104 inventive wash drawings for his series Divertimenti per li ragazzi (Diversions for Children). The drawings illustrate the life of the tragicomic commedia dell’arte figure Punchinello (identified by his white garments, conical hat, and beaked mask), a popular protagonist in Italian theater and puppetry starting in the 1600s. Punchinello collapses on the road takes place just before the protagonist’s death. Having suffered a fall, he is surrounded by eleven concerned companions and three lamenting women. While the Divertimenti presents Punchinello as a kind of everyman, Tiepolo also frequently referenced the life of Christ. This drawing recalls the scene of Christ falling as he carries the cross.

Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo

Italian, 1727–1804

Punchinello collapses on the road, ca. 1797–1804

Pen and brown ink, and brush and brown washes, over traces of charcoal

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.869

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Art Institute of Chicago Imaging Department

Polidoro Caldara, called Polidoro da Caravaggio

Divided into three distinct scenes, this composition focuses on the events following Christ’s Crucifixion. At center, a large group of followers mourns over his slumped, dead body. Christ’s tomb is prepared for his burial at left, and the bodies of the two thieves who were crucified alongside him are carried away at upper right. The drawing typifies Polidoro’s work in pen and ink, featuring reduced forms composed of agitated strokes and rapid hatching.

Polidoro Caldara, called Polidoro da Caravaggio

Italian, ca. 1499–ca. 1543

The Lamentation of Christ, ca. 1527–35

Pen and brown ink, with splatters of green, gray, and pink paint, and touches of white opaque watercolor

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.837

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Art Institute of Chicago Imaging Department

Vasily Kandinsky

The shifting forms and colors in this watercolor surge forward and recede, forming a completely abstract panorama at first glance. Further examination reveals hints of a landscape, however, including a hilltop town illuminated by a deep-red sun over a tower at upper left. Forced by World War I to leave Germany, where he had lived since 1898, Kandinsky returned to Moscow in 1914. There, restricted by limited space and financial resources, he concentrated on small- scale works primarily in watercolor, such as this one.

Vasily Kandinsky

Russian, 1866–1944

Untitled, ca. 1915

Watercolor and opaque watercolor

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray in memory of Buddy Mayer; 2018.753

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

© Vasily Kandinsky / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

Giovanni Antonio Canal, called Canaletto

A native of Venice, Canaletto specialized in charmingly descriptive views of the city, which were highly sought after by European aristocrats traveling to Italy on the Grand Tour. This carefully structured landscape places the viewer amid a busy market at the Molo, a pier adjacent to the Doge’s Palace, seen at left. The meticulously described architectural features of the palace contrast with the calligraphic, somewhat abstracted rendering of figures populating the foreground. The drawing exemplifies Canaletto’s late work in its combination of brown ink and gray wash and his use of the paper’s white reserves to evoke sunlight playing over masonry.

Giovanni Antonio Canal, called Canaletto

Italian, 1697–1768

The Riva degli Schiavoni seen from the market at the pier, after 1755

Pen and iron- gall ink, and brush and gray wash, over traces of graphite

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.836

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

John Marciari: Canaletto is most famous, of course, for his painted views of Venice, but he also produced many highly finished drawings, which, though reduced to the white of the page, brown ink lines, and gray wash, have all the life of his colorful paintings. In this example, he takes one of the most recognizable sights of Venice, a view of the Doge's Palace at left, the columns of St. Theodore and St. Mark, and the Piazza de San Marco, and the distant view along the Riva degli Schiavoni. Rather than give a stately placid depiction, however, Canaletto animates the scene in unexpected ways by including the disarray of market stalls in the foreground, for example, and by distorting the perspective so that the deeply shadowed column of St. Theodore towers in the foreground, a notable contrast to the brightly lit façade of the palace, but one echoed by the dark clouding sky. While the profusion of detail speaks to the careful planning of the drawing, it is interesting to observe just how schematic Canaletto's forms are, especially in his late work. He had a seemingly magical ability to create wonderfully expressive figures with little more than a squiggle of line and a few dots of wash.

Johan Tobias Sergel

The Swedish draftsman and sculptor Johan Tobias Sergel trained with Pierre-Hubert L’Archevêque, a French artist active at the royal court in Stockholm. Later, Sergel spent several months studying at the Royal Academy in Paris. This early drawing reveals his resultant debt to French art, especially the light and sinuous graphic style of François Boucher (whose work appears elsewhere in the exhibition). The ambitious, highly theatrical composition illustrates a scene from Homer’s epic poem The Iliad. Seated at right, Agamemnon, the leader of the Greek army laying siege to Troy, agrees to return the abducted daughter of the Trojan priest Chryses, demanding in exchange Achilles’s favorite concubine. Furious at the idea, Achilles, seen at left, draws his sword but is held back by the apparition of the goddess Athena.

Johan Tobias Sergel

Swedish, 1740–1814

Achilles restrained by Athena in Agamemnon’s tent, from “The Iliad,” Book I, 1765–66

Black chalk

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.887

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Art Institute of Chicago Imaging Department

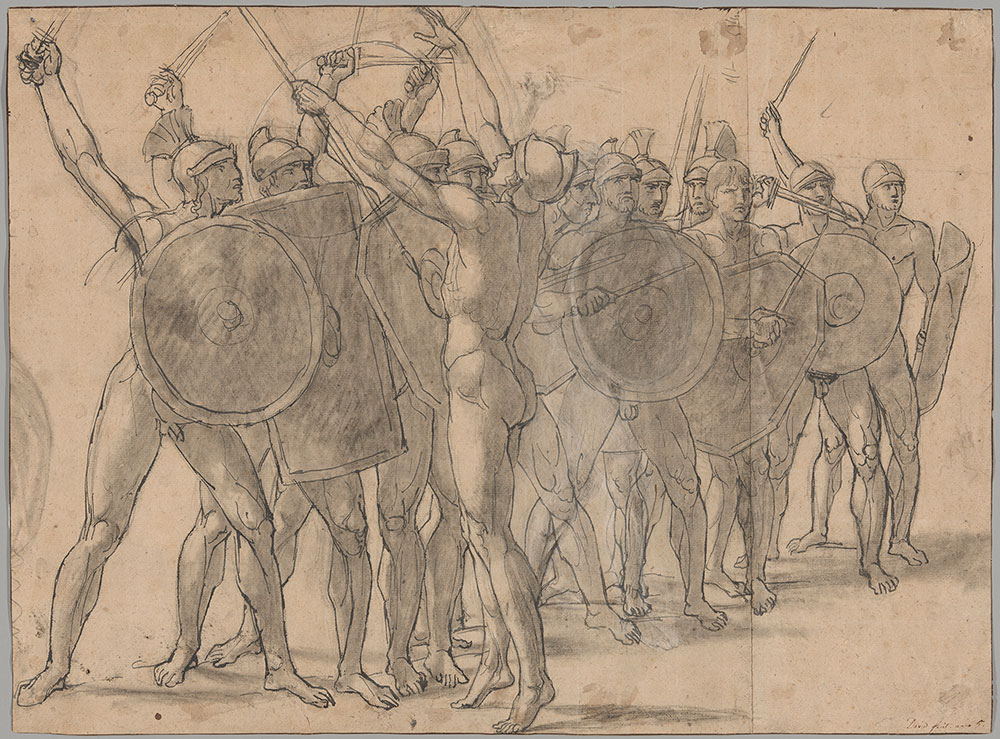

Jennifer Tonkovich: The second half of the 18th century witnessed an onslaught of political upheavals throughout Europe. It also brought an increasingly public role for women. Narrative subjects from Greek and Roman history were imbued with additional meaning in this mutable, increasingly politicized climate. Both Johan Tobias Sergal and Jacques-Louis David seized on subjects that juxtaposed the roles of men and women in moments of conflict. Sergal chose to depict Athena stopping Achilles' hand, the goddess preventing further bloodshed over the abduction of Achilles' daughter. A group of soldiers lurk behind Sergal's seated Agamemnon, reminding us of the simmering threat. David's sketch displayed nearby outlines a mob of battle-ready Sabine men openly wielding knives and shields. In the related painting, the Sabine women, torn by their divided loyalty, risk themselves and their children as they intervene between their tribe and their new families. The juxtaposition of these sheets, which bracket the French Revolution is telling. For Sergal divine intervention halts the impending attack. While for David, an ardent revolutionary, it is female citizens of the Roman Republic who heroically bring resolution to the conflict.

Jacques Louis David

This large, bold drawing was part of David’s preparatory work for The Intervention of the Sabine Women. In the legendary origin story of ancient Rome, the city’s founder Romulus and his men abducted women from the neighboring Sabine tribe, forcing them into marriage. When the vengeful Sabines declared war on the Romans, Romulus’s wife and the other Sabine women threw themselves and their infants between the two armies and successfully stopped a war. David conceived of the painting while in prison for his active involvement in the French Revolution and allegiance to Maximilien Robespierre, one of its principal leaders. The subject allowed him to deliver a powerful postrevolutionary message of political and familial reconciliation.

Jacques Louis David

French, 1748–1825

Nude soldiers gesticulating with their weapons, 1796–97

Black chalk, and pen and ink, with touches of white chalk

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.841

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Art Institute of Chicago Imaging Department

Hendrik Goltzius

In drawings, prints, and paintings produced throughout his career, Goltzius often returned to images of ancient warriors and mythical heroes. Despite its relatively small size, this study of a helmeted figure in an antique- inspired military costume captures the feeling of heroic grandeur that the artist aimed to achieve in such works. Goltzius’s drawing style is fluid and loose, suggesting confident and speedy execution. He strategically placed touches of red chalk to describe the warrior’s skin tone, adding a painterly flourish to the image.

Hendrik Goltzius

Dutch, 1558–1617

Bust of a warrior, ca. 1597–1600

Black chalk, with red chalk, and touches of white chalk

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.849

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Art Institute of Chicago Imaging Department

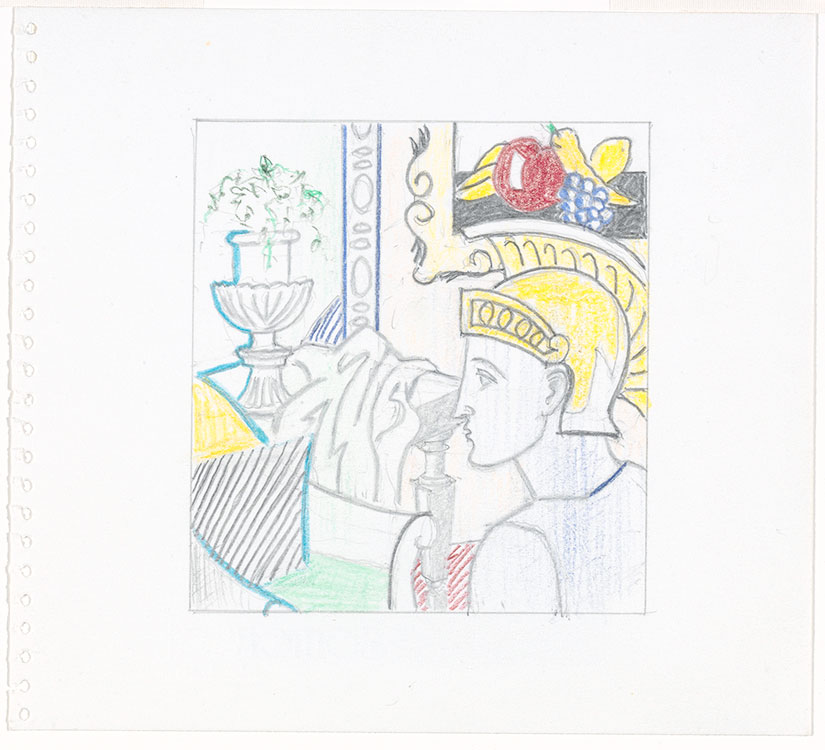

Roy Lichtenstein

In the 1990s, Lichtenstein created a body of work called Interiors, in which he mixed references to classical antiquity, the Renaissance, and modernism. He also used visual signs plucked from his own illustrious career, such as his characteristic Ben-Day dots. Created in the last year of Lichtenstein’s life, this drawing is a study for a painting commissioned by the fashion designer Gianni Versace. A confusedlooking Ajax, a hero of Greek mythology, finds himself in an eclectically decorated room in which styles float free of their contexts and hatch marks are divorced from their descriptive function.

Roy Lichtenstein

American, 1923–1997

Study for “Interior with Ajax,” 1997

Graphite and colored pencil on page removed from a sketchbook

Richard and Mary L. Gray, promised gift to the Morgan Library & Museum

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

© Estate of Roy Lichtenstein

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.

Rachel Federman: What would Ajax, a hero of Greek mythology make of an ornate modern interior? That seems to be the question posed in this drawing. Roy Lichtenstein used his signature comic book style and his deep knowledge of art history to interrogate the very notion of style, whether in art or popular culture. Like Ajax, the anachronistic urn and arbitrary swath of drapery at the center of the drawing signaled a classical as a generalized style. References to classical antiquity roam through the history of Western art and architecture like free-floating signifiers. Consider, for example, the classical archetypes conjured in Hendrik Goltzius's bust of a warrior, and Jacques-Louis David's nude soldiers gesticulating with their weapons both on view nearby. Despite their evocation of a distant time and place, work such as these claim the classical as an accessible and malleable cultural touchstone. Greco-Roman antiquity was also the dominant theme of the opulent Miami home of Italian fashion designer, Gianni Versace, who commissioned the painting for which Lichtenstein's drawing serves as a study. The artist assuredly had this destination in mind when he conceived this witty composition.

Giorgio Vasari

A candle in hand, crowned with a halo of light, the winged personification of eternity sits astride a globe in the celestial sphere. Vasari enhanced the drawing’s luminosity with his virtuosic technique, overlaying discrete yet tightly packed strokes of white opaque watercolor on blue paper. The artist made the drawing for a ceiling fresco decorating the refectory of the monastery church of Monteoliveto in Naples. The study is typical of the allegorical imagery that Vasari developed in the early 1540s and to which he would return throughout his career.

Giorgio Vasari

Italian, 1511–1574

Allegory of eternity, 1544–45

Pen and brown ink, and brush and brown wash, over black chalk, heightened with white opaque

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Richard and Mary L. Gray; 2019.871

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

Photography by Art Institute of Chicago Imaging Department

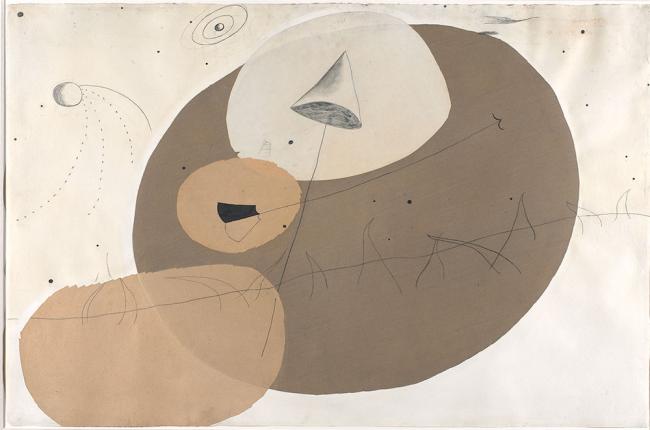

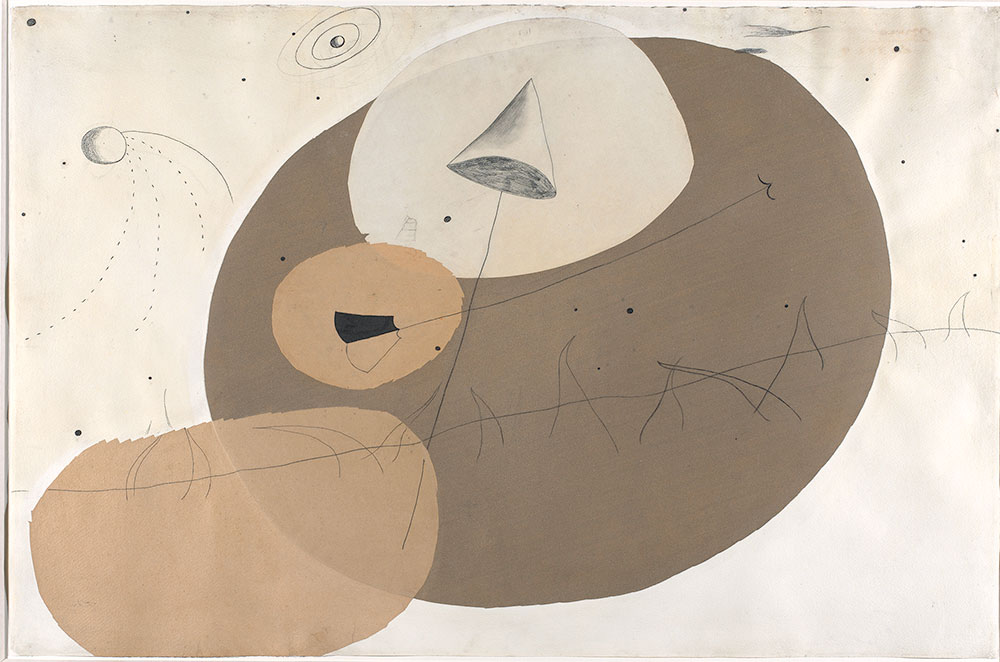

Joan Miró

The drawn forms in Miró’s Untitled—a conical, tipped weather vane, planets and comets in orbit, and a flaming horizon line—are schematically rendered yet recognizable. They float amid an abstract landscape of paper- collage circles in rust, brown, tan, and white. Untitled is one of twenty- two large- scale, chromatically austere collages Miró made between July and November 1929. In these works, he kept his drawn lines to a minimum. Miró described his collages as “drawings with new explorations into substance” and as “training exercises, shadowboxing, so as to hit harder and harder, in a tougher and more energetic way.”

Joan Miró

Spanish, 1893–1983

Untitled, 1929

Collage of cut and pasted papers (including flocked paper), and black Conté crayon, with white opaque watercolor, pen and black ink, and traces of graphite

Richard and Mary L. Gray, promised gift to the Art Institute of Chicago

Gray Collection Trust, Art Institute of Chicago

© Joan Miró / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photography by Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics Inc.