Almost a Remembrance: Belle Greene’s Keats

I think Poetry should surprise by a fine excess and not by Singularity—it should strike the Reader as a wording of his own highest thoughts, and appear almost a Remembrance —

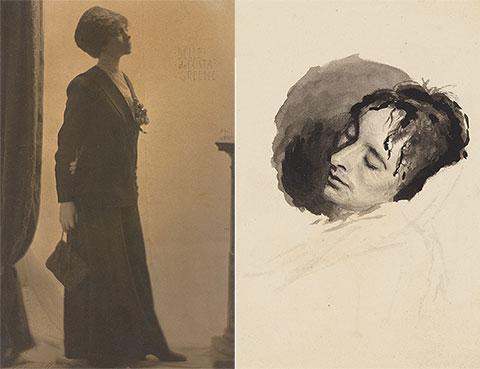

On 23 February 1821, the Romantic poet John Keats (1795–1821) died in Rome from tuberculosis. Marking the two-hundredth anniversary of his death, this exhibition considers the Morgan’s Keats collection through the lens of the library’s first director, Belle da Costa Greene (1879–1950)—a self-described “Keats lover.” Appointed during the summer of 1905 as J. Pierpont Morgan’s private librarian, Greene developed the collection and became an internationally renowned expert in rare books and manuscripts. She built, catalogued, and interpreted the Morgan’s Keats holdings, featured here through books, correspondence, literary drafts, and archival documents.

In a letter Greene acquired for the library, Keats wrote that “Poetry . . . should strike the Reader as a wording of his own highest thoughts, and appear almost a Remembrance.” Bringing together institutional and literary history, this installation remembers a great British poet through the work and vision of one of the world’s greatest librarians.

This online exhibition was created in conjunction with the exhibition Almost a Remembrance: Belle Greene’s Keats on view February 17 through August 15, 2021.

Right: Joseph Severn, portrait sketch of John Keats, 1821. MA 214.7. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1909.

Left: Clarence White, full-length photographic portrait of Belle da Costa Greene, ca. 1910(?).ARC 2821. Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum.

"A thing of beauty is a joy forever"

John Keats began writing poetry in 1814 and would publish his first book of collected poems three years later. But it was in 1818, with the publication of Endymion: A Poetic Romance, that Keats became more widely recognized for his verse, even if that recognition was not entirely positive. Keats regarded his 4,000-line verse romance Endymion as a creative experiment—a “Pioneer,” a “great trial of invention,” a “feverish attempt, rather than a deed accomplished.” Envisioning a literary career in the mold of Virgil, Dante, or Milton, he felt compelled to try his hand at writing a long poem, asking, in a letter to a friend, “Did our great Poets ever write short Pieces?”

Endymion follows the wanderings of its eponymous shepherd-hero, whose love for the moon goddess Cynthia takes him through sylvan dreamscapes, underground chambers, and the ocean’s “hollow vast.” The poem’s lush imagery, sometimes overwrought, conjures up a “mazy world / Of Silvery enchantment” (I.460–61), a realm of gentle rills and cloistered bowers. But as Keats himself admitted, the poem served as a testing ground for future literary endeavors: it was not his best work, but it presaged better things to come.

Inveterate in their dislike of progressive writers such as Leigh Hunt and Keats, Tory critics John Gibson Lockhart and John Wilson Croker wrote searing reviews of Endymion in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine and the Quarterly Review, attacking the poem’s politics as much as its literary merit. Lockhart characterized the poem’s enjambed lines and narrative digressions as indecorous and politically suspect, while Croker dismissed Endymion outright as “nonsense,” claiming he could read only the first of its four books. The infamous bad press hurled at Endymion created the myth of a thin-skinned Keats “snuffed out by an Article,” as Lord Byron quipped in his mock-epic poem Don Juan (1819–24). Though undoubtedly affected by these reviews, in reality Keats was resilient, persisted in his craft, and went on to write some of the most celebrated lyric poetry in English.

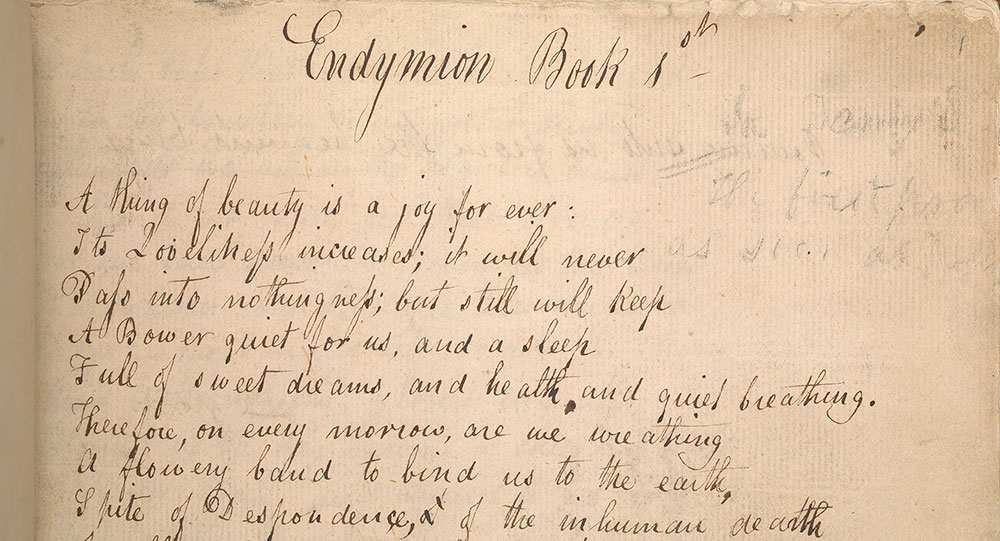

No early drafts of Endymion survive. The manuscript at the Morgan is for the most part a fair copy prepared for the printer, though it does bear some revision in Book I. The first page of the manuscript, includes a line and a half deleted by Keats before the poem went to press—a line referencing King Arthur (“and before us dances / Like glitter on the points of Arthur’s lances”).

John Keats, detail of Endymion: A Poetic Romance, p. 1. Autograph manuscript, 1818. MA 208. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1897.

Endymion: A Poetic Romance, p. 1

John Keats, Endymion: A Poetic Romance, p. 1. Autograph manuscript, 1818. MA 208. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1897.

Endymion Book 1st

A thing of beauty is a joy for ever:

Its Loveliness increases; it will never

Pass into nothingness; but still will keep

A Bower quiet for us, and a sleep

Full of sweet dreams, and health and quiet breathing.

Therefore, on every morrow, are we wreathing

A flowery band to bind us to the earth,

Spite of Despondence, of the inhuman dearth

Of noble natures, of the gloomy wdays,

Of all the unhealthy and o’er-darkened ways

Made for our searching: yes, in spite of all

Some shape of beauty moves away the Pall

From our dark spirits, and before us dances

Like glitter on the points of Arthur’s lances.

Of these bright powers are Such the sun, and the Moon

Trees old, and young sprouting a shady boon

For simple sheep; of these and such are daffodils

And With the green world they live in; and clear rills

That for themselves a cooling covert make

‘Gainst the hot season; the mid forest brake

Rich with a sprinkling of fair Muskrose blooms:

Of these And such too are is the grandeur of the dooms

We have imagined for the mighty dead;

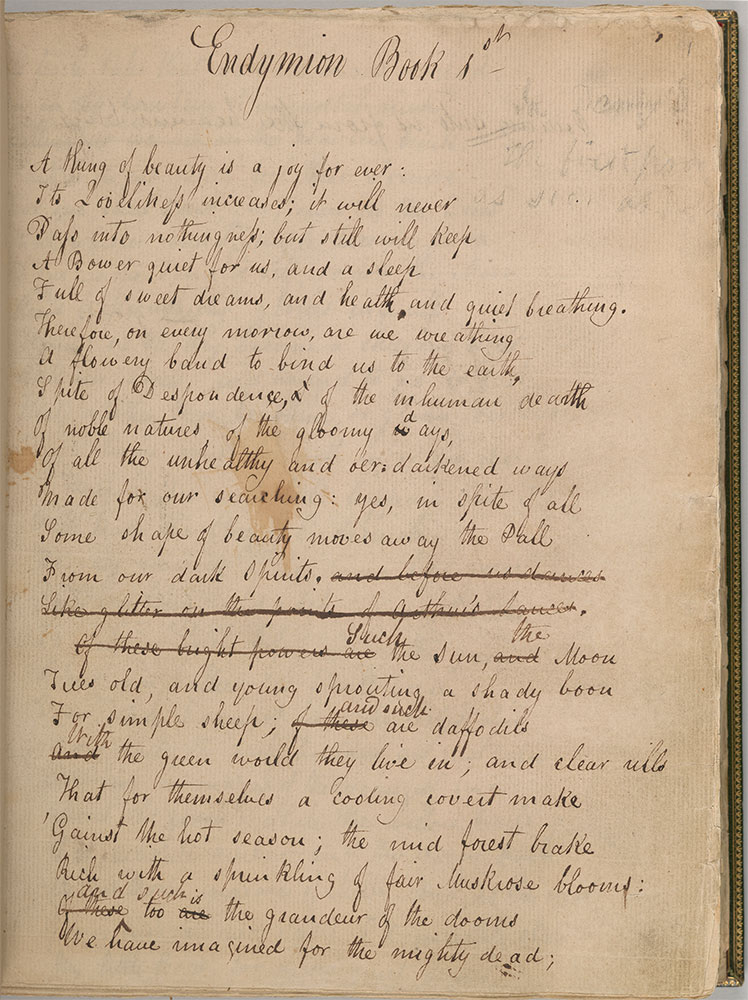

Robert Underwood Johnson letter, p.1

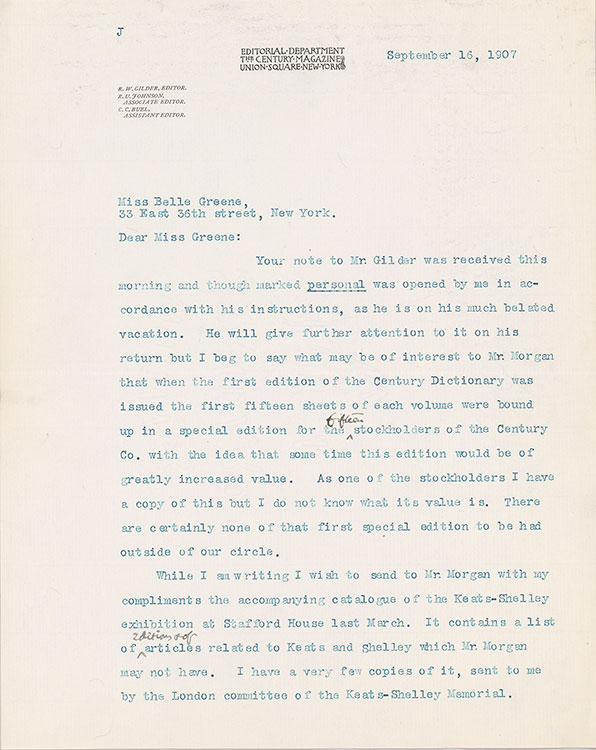

Endymion was the first of many Keats manuscripts purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, who bought it from the London bookseller J. Pearson & Co. for £770 in 1897. It was among his earliest acquisitions of literary manuscripts, and it became well known that Morgan was the owner. In 1907, the Associate Editor of The Century Magazine, Robert Underwood Johnson (1853–1937), wrote to Belle Greene asking to obtain photographs of the manuscript for the archives of the Keats-Shelley Memorial House in Rome, which would open in 1909. Greene would visit the house in September 1910.

Robert Underwood Johnson, typed letter to Belle da Costa Greene, 16 September 1907, p. 1. ARC 1310. Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum.

Robert Underwood Johnson letter, p.2

Endymion was the first of many Keats manuscripts purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, who bought it from the London bookseller J. Pearson & Co. for £770 in 1897. It was one of his earliest acquisitions of a literary manuscript, and it became well known that Morgan was the owner. In 1907, the Associate Editor of The Century Magazine, Robert Underwood Johnson (1853–1937), wrote to Belle Greene asking to obtain photographs of the manuscript for the archives of the Keats-Shelley Memorial House in Rome, which would open in 1909. Greene would visit the house in September 1910.

Robert Underwood Johnson, typed letter to Belle da Costa Greene, 16 September 1907, p. 2. ARC 1310. Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum.

An Early Keats Purchase by Greene

The origin of Belle Greene’s interest in John Keats is obscure. Though we know she enjoyed reading poetry—especially Shelley, Keats, Dante, and Baudelaire—it is unclear whether her taste in literature was cultivated in childhood by her father, the educator and activist Richard T. Greener (1844–1922), or later in life. Extant archives offer tantalizing glimpses of Greene’s interest in Keats, though many questions remain: what were her favorite Keats poems, for instance?

The origin of Belle Greene’s interest in John Keats is obscure. Though we know she enjoyed reading poetry—especially Shelley, Keats, Dante, and Baudelaire—it is unclear whether her taste in literature was cultivated in childhood by her father, the educator and activist Richard T. Greener (1844–1922), or later in life. Extant archives offer tantalizing glimpses of Greene’s interest in Keats, though many questions remain: what were her favorite Keats poems, for instance?

By 1909, a few years after starting her position as J. Pierpont Morgan’s Librarian, Greene was actively purchasing Keats manuscripts for the collection. Her first documented acquisition of a Keats manuscript is a lengthy journal-letter sent by Keats in September 1819 to his brother George and sister-in-law Georgiana, both of whom had been living in America since the summer of 1818. Keats customarily sent them long, descriptive letters like this one, composed over the course of ten days; these letters touched upon his life and work and sometimes included copies of his poetry. Greene acquired the letter at the 1909 auction of Louis J. Haber’s British literature collection, with the bookselling firm George H. Richmond acting as her agent. A.J. Bowden, an employee at the firm, described the twenty-eight page manuscript as “the best thing of its kind ever offered.”

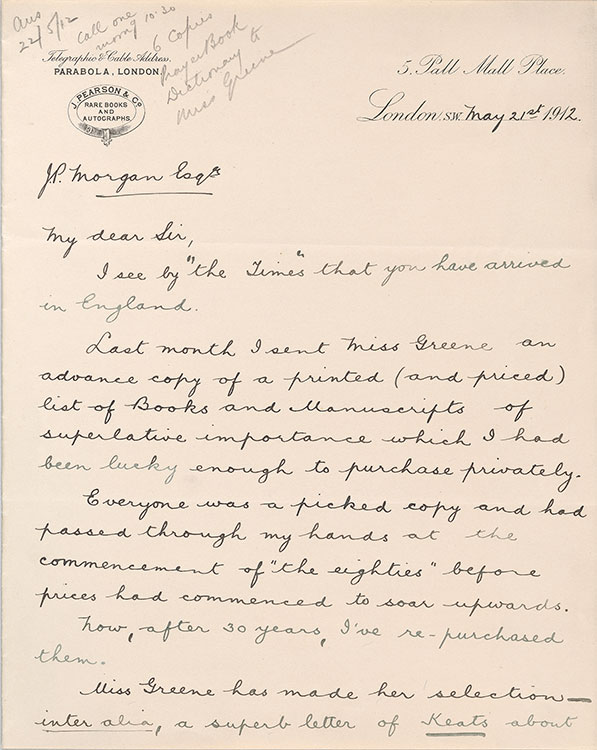

Belle Greene’s most important early Keats acquisition came in 1912, when she procured a letter written by Keats in February 1818 to his publisher John Taylor (1781–1864). Frank Wheeler of J. Pearson & Co., the same dealer who sold the Endymion manuscript, offered the letter to Greene, as described in a letter to J. Pierpont Morgan:

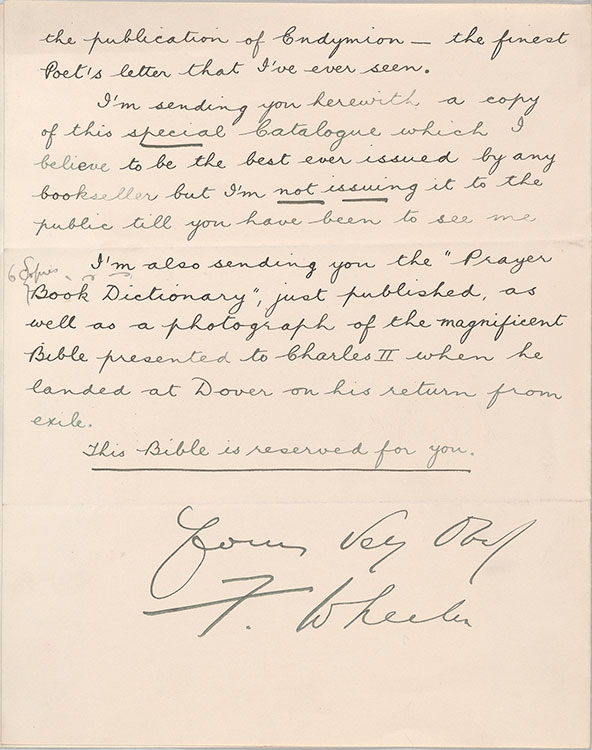

“Last month I sent Miss Greene an advance copy of a printed (and priced) list of Books and Manuscripts of superlative importance which I had been lucky enough to purchase privately … Miss Greene has made her selection— inter alia, a superb letter of Keats about the publication of Endymion— the finest Poet’s letter that I’ve ever seen.”

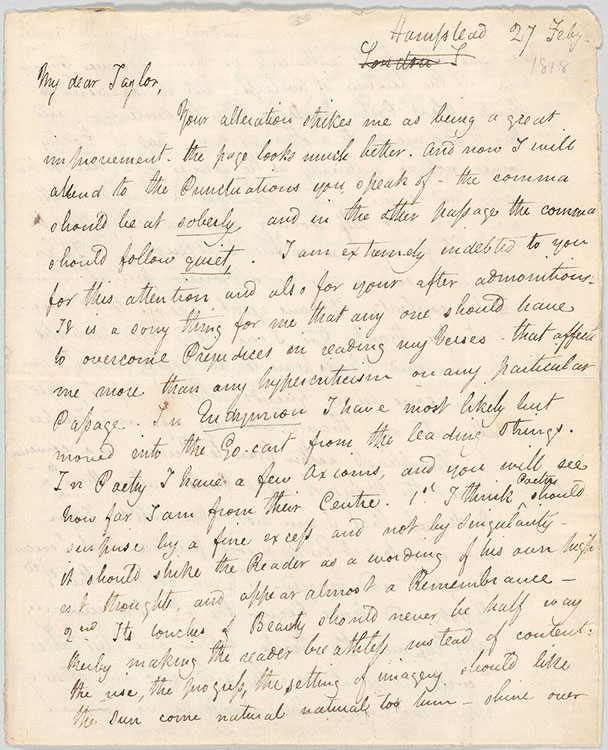

The acquisition shows Greene’s discerning eye for collection development, as the letter, sent to Keats’s publisher John Taylor, contextualizes the publication of Endymion in interesting ways. Keats responds to editorial queries about punctuation and proof corrections while also commenting more generally on the role of the poem in his fledgling career. As Keats writes, using a rather obscure metaphor, “In Endymion I have most likely but moved into the Go-cart from the leading strings.” (A “go-cart” is a walker for babies and would have marked a progression from “leading strings,” also used to aid small children learning to walk.)

Most notably, the letter outlines Keats’s three “Axioms” for poetry:

1st I think Poetry should surprise by a fine excess and not by Singularity— it should strike the Reader as a wording of his own highest thoughts, and appear almost a Remembrance—

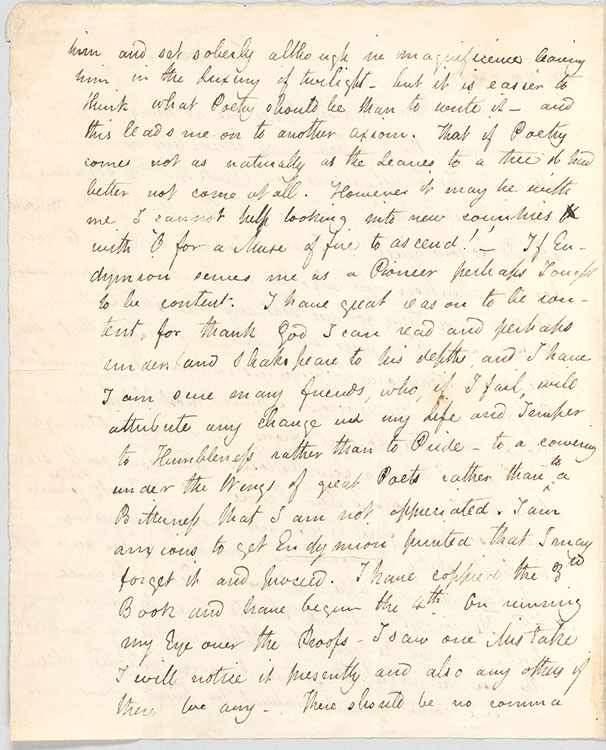

2nd Its touches of Beauty should never be half way thereby making the reader breathless instead of content: the use, the progress, the setting of imagery should like the sun come natural [,] natural too [sic] him—shine over him and set soberly although in magnificence leaving him in the luxury of twilight. but it is easier to think what Poetry should be than to write it —

[3rd] and this leads me on to another axiom. That if Poetry comes not as naturally as the Leaves to a tree it had better not come at all.

This famous commentary on poetics exists in the absence of any formal work by Keats on literary theory or criticism: unlike Coleridge, with his Biographia Literaria (1817), or Wordsworth, with his “Preface” to Lyrical Ballads (1800), Keats did not publish works of literary criticism but rather expressed such ideas in private letters.

The first of the axioms, from which this exhibition takes its title, speaks to the authenticity of imaginative expression, which seems to approximate a reader’s own thoughts and resemble a deeply held memory. The notion of poetry “surpris [ing] by a fine excess” complements the second axiom’s focus on how a writer should deploy imagery and “its touches of Beauty.” The third and final axiom is certainly the most famous, though Keats undercuts its impact by admitting, at the end of axiom two, that “it is easier to think what Poetry should be than to write it.”

Baron Adolf De Meyer, Belle Greene [photograph], ca. 1910? ARC 1664. Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum

Frank Wheeler letter to J. Pierpont Morgan, p.1

Frank Wheeler, letter to J. Pierpont Morgan, 12 May 1912, p. 1. ARC 1310. Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum.

p. 1

Aus 22/5/12

Call one morn[in]g 10:30

6 copies Prayer Book Dictionary to Miss Greene

May 21st 1912

J.P. Morgan Esqr

My dear Sir,

I see by “the Times” that you have arrived

in England.

Last month I sent Miss Greene an

advance copy of a printed (and priced)

list of Books and Manuscripts of

superlative importance which I had

been lucky enough to purchase privately.

Everyone was a picked copy and had

passed through my hands at the

commencement of “the eighties” before

prices had commenced to soar upwards.

Now, after 30 years, I’ve re-purchased

them.

Miss Greene has made her selection—

inter alia, a superb letter of Keats about

Frank Wheeler letter to J. Pierpont Morgan, p.2

Frank Wheeler, letter to J. Pierpont Morgan, 12 May 1912, p. 1. ARC 1310. Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum.

p. 2

the publication of Endymion—the finest

Poet’s letter that I’ve ever seen.

I’m sending you herewith a copy

of this special Catalogue which I

believe to be the best ever issued by any

bookseller but I’m not issuing it to the

public till you have been to see me

I’m also sending you the “Prayer

Book Dictionary”, just published, as

well as a photograph of the magnificent

Bible presented to Charles II when he

landed at Dover on his return from

exile.

This Bible is reserved for you.

Yours very obli[gingly?]

F. Wheeler

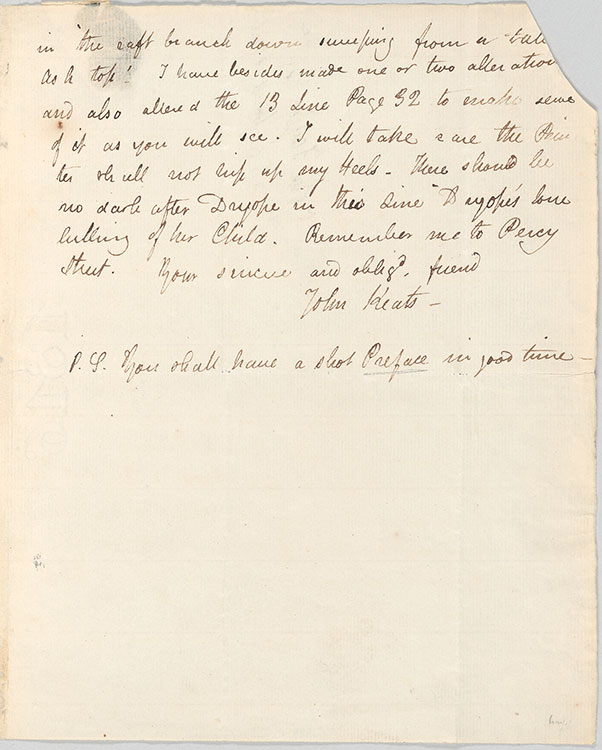

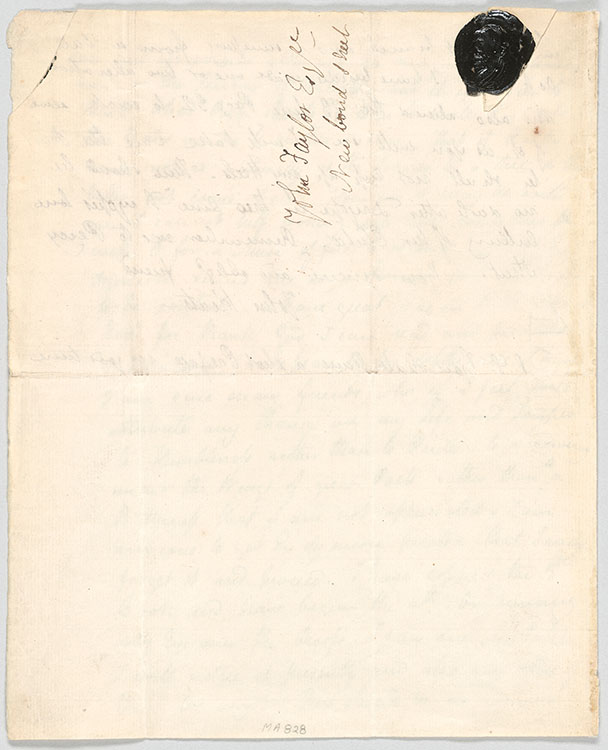

John Keats letter to John Taylor, p. 1

John Keats, letter to John Taylor, 27 February 1818, p. 1. MA 828. Purchased by Belle da Costa Greene on behalf of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1912.

p. 1

Hampstead 27 Feb[ruar]y

London L 1818

My dear Taylor,

Your alteration strikes me as being a great

improvement. the page looks much better. And now I will

attend to the Punctuations you speak of — the comma

should be at soberly, and in the other passage the comma

should follow quiet,. I am extremely indebted to you

for this attention and also for your after admonitions.

It is a sorry thing for me that any one should have

to overcome Prejudices in reading my Verses. that affects

me more than any hypercriticism on any particular

Passage. In Endymion I have most likely but

moved into the Go-cart from the leading strings.

In Poetry I have a few Axioms, and you will see

how far I am from their Centre. 1st I think Poetry should

surprise by a fine excess and not by Singularity —

it should strike the Reader as a wording of his own highest

thoughts, and appear almost a Remembrance —

2nd Its touches of Beauty should never be half way

thereby making the reader breathless instead of content:

the use, the progress, the setting of imagery should like

the sun come natural[,] natural too [sic] him—shine over

John Keats letter to John Taylor, p. 2

John Keats, letter to John Taylor, 27 February 1818, p. 2. MA 828. Purchased by Belle da Costa Greene on behalf of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1912.

p. 2

him and set soberly although in magnificence leaving

him in the luxury of twilight. but it is easier to

think what Poetry should be than to write it — and

this leads me on to another axiom. That if Poetry

comes not as naturally as the Leaves to a tree it had

better not come at all. However it may be with

me I cannot help looking into new countries

with ‘O for a Muse of fire to ascend!’— If Endymion

serves me as a Pioneer perhaps I ought

to be content: I have great reason to be content,

for thank God I can read and perhaps

understand Shakspeare to his depths, and I have

I am sure many friends, who, if I fail, will

attribute any change in my life and Temper

to Humbleness rather than to Pride — to a cowering

under the Wings of great Poets rather than to a

Bitterness that I am not appreciated. I am

anxious to get Endymion printed that I may

forget it and proceed. I have coppied [sic] the 3rd

Book and have begun the 4th. On running

my Eye over the Proofs, I saw one Mistake

I will notice it presently and also any others if

there by any. There should be no comma

John Keats letter to John Taylor, p. 3

John Keats, letter to John Taylor, 27 February 1818, p. 3. MA 828. Purchased by Belle da Costa Greene on behalf of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1912.

John Keats, letter to John Taylor, 27 February 1818, [blank]. MA 828. Purchased by Belle da Costa Greene on behalf of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1912.

p. 3

in ‘the raft branch down sweeping from a tall

ash top’ I have besides made one or two alterations

and also altered the 13 Line Page 32 to make sense

of it as you will see. I will take care the Printer

shall not trip up my Heels. There should be

no dash after Dryope in this Line ‘Dryope’s lone

lulling of her Child. Remember me to Percy

Street.

Your sincere and oblig[e]d friend

John Keats

P.S. You shall have a short Preface in good time

The Miracle Year

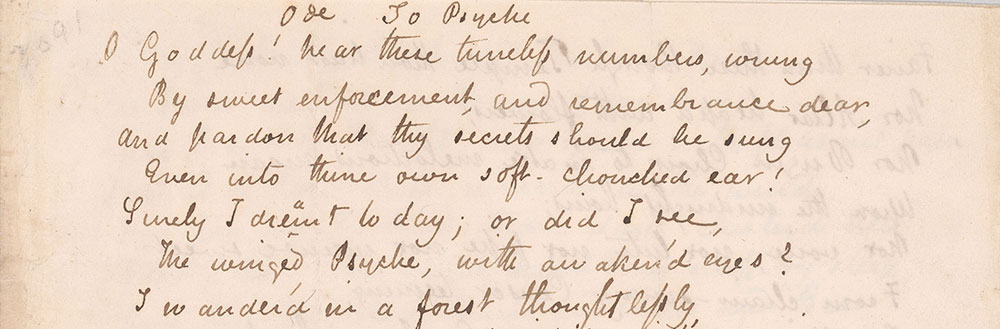

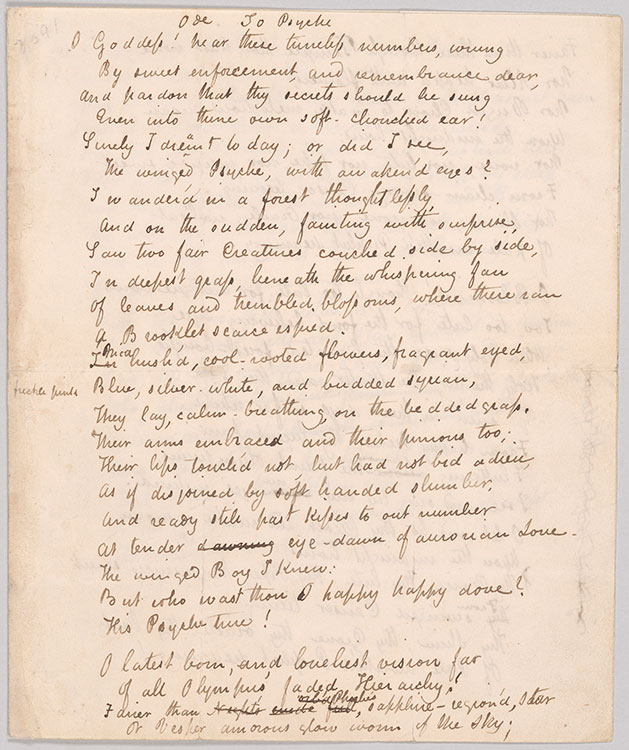

In 1819, two years before his death at age twenty-five, Keats wrote his best-known poems in an extraordinary burst of creative activity. He would complete five of his six so-called great odes in the spring of 1819—“Ode to Psyche,” “Ode to a Nightingale,” “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” “Ode on Indolence,” and “Ode on Melancholy”—and compose the sixth, “To Autumn,” that fall. Along with other celebrated poems he wrote that year, including “The Eve of St. Agnes,” “Lamia,” and “La Belle Dame Sans Merci,” the great odes would prove, in time, to secure literary immortality for Keats.

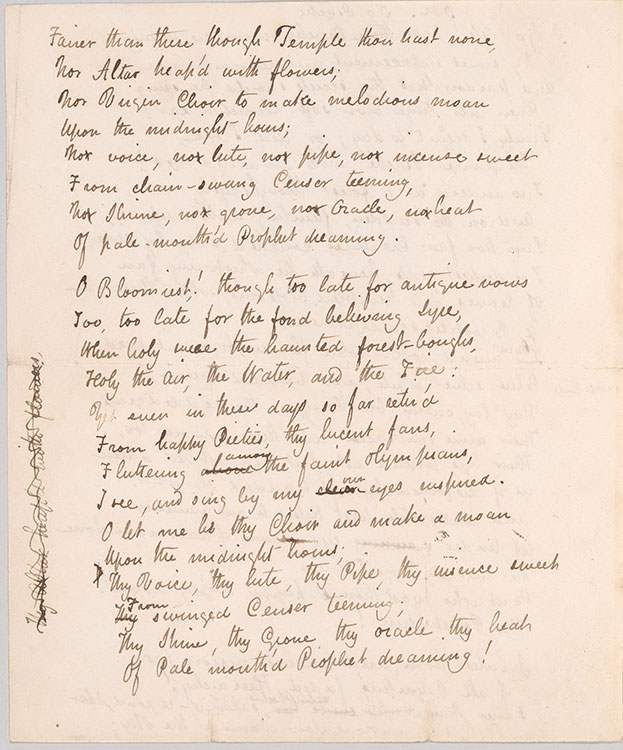

The Morgan owns the original draft of the first of these odes, completed in late April 1819. Though “Ode to Psyche” would shape the stanzaic form used in the rest of the great odes, it seems adding “Ode” to the title was somewhat of an afterthought; looking closely at the manuscript, one can see that “Ode” was written later, and slightly off to the side, of “To Psyche.” Keats recounted the composition of “Psyche” in a letter to his brother:

“it is the first and only one [i.e., poem] with which I have taken even moderate pains—I have for the most part dash’d of[f] my lines in a hurry— This I have done leisurely—I think it reads the more richly for it and will I hope encourage me to write other thing[s] in even a more peaceable and healthy spirit.”

The poem draws on the myth of Cupid and Psyche, first imagined in the second-century Metamorphoses of Apuleius and most recently (for Keats) portrayed in verse by Mary Tighe’s Psyche; or, the Legend of Love (1805). Keats knew the myth of Cupid and Psyche primarily from John Lemprière’s Bibliotheca Classica (1788), which summarizes the main elements of the story: “PSYCHE, a nymph whom Cupid married and carried into a place of bliss, where he long enjoyed her company. Venus put her to death because she had robbed the world of her son; but Jupiter, at the request of Cupid, granted immortality to Psyche.”

The speaker of “Ode to Psyche” addresses the goddess as the “latest born” of ancient deities,

Fairer than these though Temple thou hast none,

Nor Altar heap’d with flowers;

Nor Virgin Choir to make melodious moan

Upon the midnight hours.

After witnessing Cupid and Psyche “couched side by side, / In deepest grass, beneath the whispering fan / Of leaves and trembled blossoms,” the speaker resolves to devote himself to the goddess as her priest, her “pale-mouth’d Prophet dreaming”:

Yes, I will be thy Priest and build a Fane

In some untrodden Region of my mind,

Where branched thoughts, new grown with pleasant pain

Instead of Pines shall murmur in the wind.

The poem goes on to envision a temple of the imagination—“a rosy sanctuary . . . dress[ed] / With the wreathed trellis of a working brain”—built to exalt the goddess, whose name in Greek means “soul.” The striking image of the brain as a “wreathed trellis” draws its inspiration from Keats’s first career, in medicine; his 1815–16 stint as a medical student at Guy’s Hospital in Southwark exposed him to the anatomical secrets of the human body, if also traumatizing him with the potentially horrifying spectacle of pre-modern surgery.

Ode to Psyche, p.1

John Keats, “Ode to Psyche,” autograph manuscript, 1819, p. 1. MA 210.1. Acquired by J. Pierpont Morgan before 1913.

p. 1

Ode To Psyche

O Goddess! hear these tuneless numbers, wrung

By sweet enforcement, and remembrance dear,

And pardon that thy secrets should be sung

Even into thine own soft-chonched ear!

Surely I dreamt today; or I did I see,

The winged Psyche, with awaken’d eyes?

I wander’d in a forest thoughtlessly,

And on the sudden, fainting with surprise,

Saw two fair Creatures couched side by side,

In deepest grass, beneath the whispering fan

Of leaves and trembled blossoms, where there ran

A Brooklet scarce espied.

In Mid hush’d, cool-rooted flowers, fragrant eyed,

Blue, silver-white, and budded syrian,1

They lay, calm-breathing, on the bedded grass,

Their arms embraced and their pinions too;

Their lips touch’d not, but had not bid adieu,

As if disjoined by soft handed slumber,

And ready still past kisses to out number

At tender dawning eye-dawn of aurorian Love.

The winged Boy I knew:

But who wast thou O happy happy dove?

His Psyche true!

O latest born, and loveliest vision far

Of all Olympus’ faded Hierarchy!

Fairer than Night’s wide full orb’d Phoebe’s, sapphire-region’d, star

Or Vesper amorous glow worm of the sky;

- “freckle pink” written by Keats in the left margin

Ode to Psyche, p.2

John Keats, “Ode to Psyche,” autograph manuscript, 1819, p. 2. MA 210.1. Acquired by J. Pierpont Morgan before 1913.

p. 2

Fairer than these though Temple thou hast none,

Nor Altar heap’d with flowers;

Nor Virgin Choir to make melodious moan

Upon the midnight hours;

Nor voice, nor lute, nor pipe, nor incense sweet

From chain-swung Censer teeming,

Nor shrine, nor grove, nor oracle, nor heat

Of pale-mouth’d Prophet dreaming.

O Bloomiest! Though too late for antique vows

Too, too late for the fond believing Lyre,

When holy were the haunted forest-boughs,1

Holy the air, the water, and the Fire:

Yet even in these days so far retir’d

From happy Pieties, thy lucent fans,

Fluttering above among the faint Olympians,

I see, and sing by my clear own eyes inspired.

O let me be thy Choir and make a moan

Upon the midnight hours;

Thy Voice, thy lute, thy Pipe, thy insence [sic] sweet

Thy From swinged Censer teeming;

Thy Shrine, thy Grove, thy oracle, thy heat

Of Pale mouth’d Prophet dreaming!

- “Thy Altar heap’d with flowers,” crossed out and written in the left margin by Keats

Ode to Psyche, p.3

John Keats, “Ode to Psyche,” autograph manuscript, 1819, p. 3. MA 210.1. Acquired by J. Pierpont Morgan before 1913.

John Keats, “Ode to Psyche,” autograph manuscript, 1819, [blank]. MA 210.1. Acquired by J. Pierpont Morgan before 1913.

p. 3

Yes, I will be thy Priest and build a Fane

In some untrodden Region of my mind,

Where branched thoughts, new grown with pleasant pain

Instead of Pines shall murmur in the wind.

Far, far around shall those dark-cluster’d trees

Fledge the wild ridged mountains steep by steep;

And there by Zephyrs, streams, and birds and Bees

The moss-lain Dryads shall be lull’d to sleep.

And in the midst of this wide Quietness

A rosy sanctuary will I dress

With the wreath’d trellis of a working brain,

With buds and bells and stars without a name,

With all the gardener-Fancy e’er could feign,

Who plucking a thousand flower and never breeding flowers will breed plucks the same

So bower’d Goddess will I worship thee

And there shall be for thee all soft delight

That shadowy thought can win—

A bright torch, and a casement ope at night

To let, the warm love glide in.

“Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water”

In the autumn of 1817 Keats’s younger brother Tom became seriously ill with tuberculosis—the disease that claimed their mother’s life in 1810—and rapidly declined in health over the course of the ensuing year. After returning to England in the summer of 1818 from a walking tour of Scotland, Keats, who himself had contracted a bad sore throat while traveling, stayed by Tom’s side during his final months. He would die in December. Though Keats’s own health would not deteriorate significantly for another year, his period of close contact with Tom coupled with the sore throat would prove to be a fateful combination.

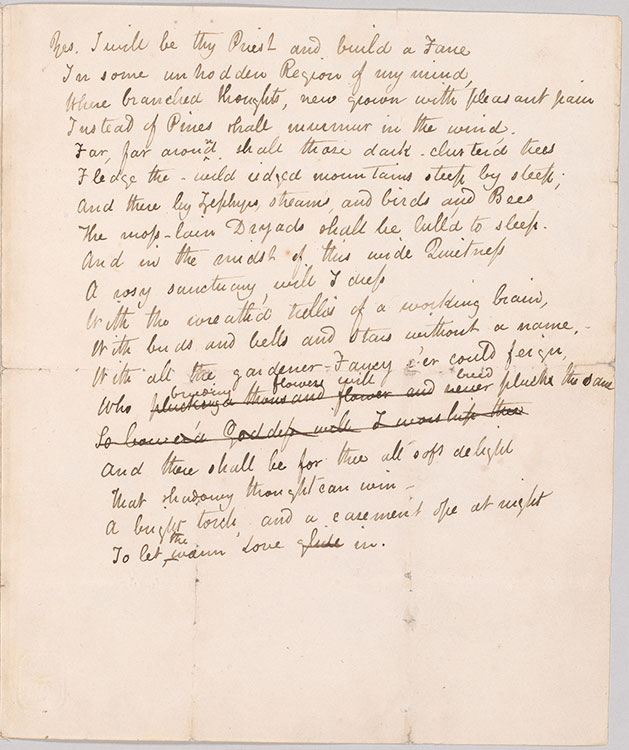

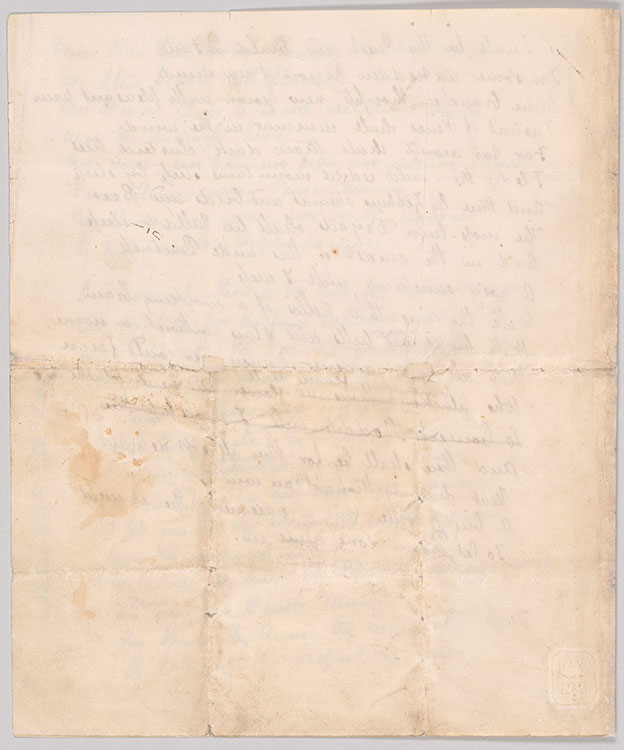

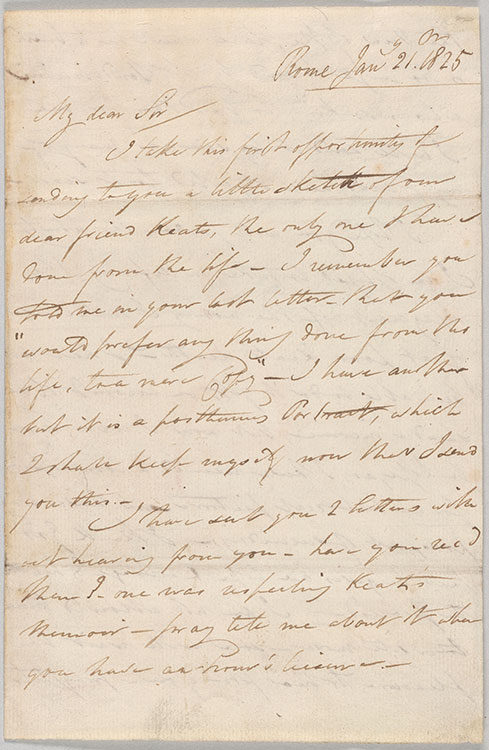

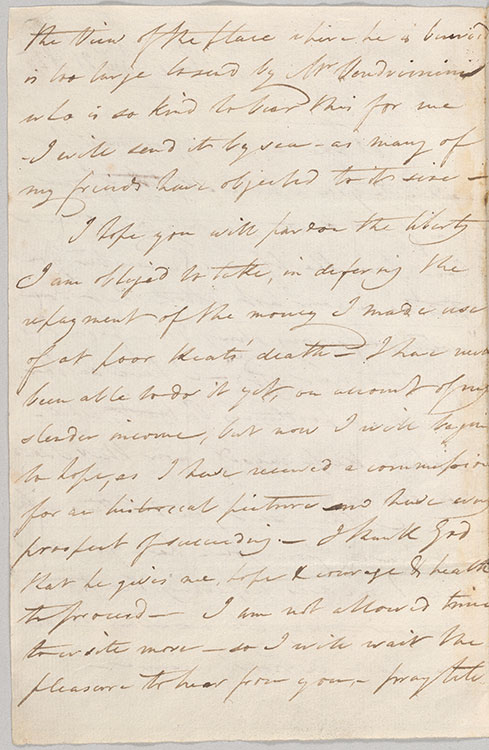

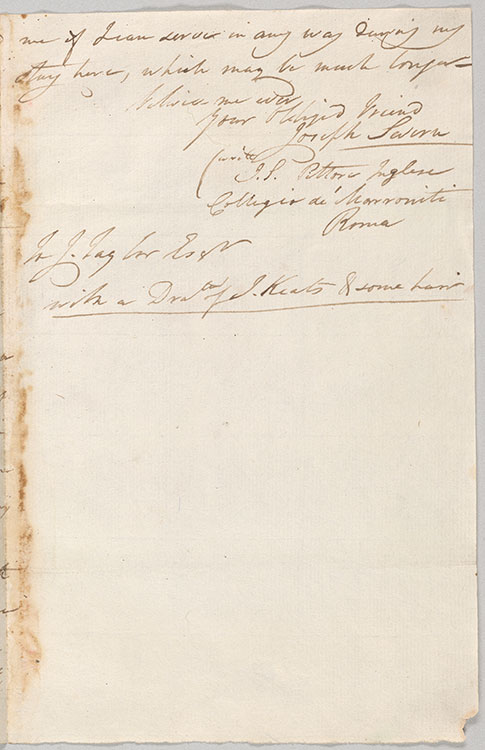

By 1820 Keats’s tuberculosis had become so severe that his doctors advised a change in climate. During the poet’s final days, spent in Rome at a house on the Piazza di Spagna, the English artist Joseph Severn (1793–1879) remained by his side. Severn sketched a famously moving deathbed portrait of Keats on 28 January 1821, with the inscription “3 o’clock [in the] morning—drawn to keep me awake[,] a deadly sweat was on him all this night.” In 1825 Severn sent this copy of the original sketch (held at the Keats-Shelley House, Rome) to Keats’s publisher John Taylor, also enclosing a letter and a lock of the poet’s hair. This collection of Keats relics, including the paper packet that once housed the lock of hair, arrived at the Morgan in 1909 as a purchase from the bookseller Frank T. Sabin. This purchase included significant Percy Bysshe Shelley manuscripts (including a poem found in his pocket after he drowned in 1822) and one additional lock of Keats’s hair, cut just before he left England for Italy. The Morgan also owns a third lock, taken by William Haslam and later in the possession of Joseph Severn.

According to the covering letter, this deathbed sketch is the original drawing Severn made “from life” as he nursed Keats in Rome. As Severn writes, “I take this first opportunity of sending to you a little sketch of our dear friend Keats, the only one I have done from the life — I remember you told me in your last letter that you ‘would prefer any thing done from the life, to a mere copy’.” This statement seems to support the idea that the Morgan version of the sketch is the original, though scholarly consensus maintains that the version at the Keats-Shelley House in Rome, donated by Severn’s daughter Eleanor Furneaux, came first. The sketch has endured as the best-known image of the poet.

Keats died on 23 February and was buried in Rome’s Protestant Cemetery, his grave marker bearing the epitaph “Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water.” Severn would be buried next to him.

Joseph Severn, portrait sketch of John Keats, 1821. MA 214.7. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1909.

Joseph Severn letter to John Taylor, p. 1

Joseph Severn, letter to John Taylor, 21 January 1825, p. 1. MA 214.6, p. 1. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1909.

p. 1

Rome Jan[uar]y 21st. 1825

My dear Sir

I take this first opportunity of

sending to you a little sketch of our

dear friend Keats, the only one I have

done from the life — I remember you

told me in your last letter that you

“would prefer any thing done from the

life, to a mere copy” — I have another

but it is a posthumous Portrait, which

I have kept myself now that I send

you this.—

I have sent you 2 letters with

out hearing from you—have you rec[eive]d

them? one was respecting Keats’s

Memoir—pray tell me about it when

you have an hour’s leisure.—

Joseph Severn letter to John Taylor, p. 2

Joseph Severn, letter to John Taylor, 21 January 1825, p. 1. MA 214.6, p. 2. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1909.

p. 2

the view of the place where he is buried

is too large to send by Mr. Vondrimini

who is so kind to bear this for me

I will send it by sea—as many of

my friends have objected to its size—

I hope you will pardon the liberty

I am obliged to take, in deferring the

repayment of the money I made use

of at poor Keats’ death—I have never

been able to do it yet, on account of my

slender income, but now I will begin

to hope, as I have received a commission

for an historical picture and have every

prospect of succeeding—thank God

that he gives me hope & courage & health

to proceed—I am not allowed time

to write more—so I will wait the

pleasure to hear from you,—pray tell

Joseph Severn letter to John Taylor, p. 3

Joseph Severn, letter to John Taylor, 21 January 1825, p. 1. MA 214.6, p. 3. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1909.

p. 3

me if I can serve in any way during my

stay here, which may be much longer—

believe me ever

your obliged friend

Joseph Severn

write

J.S. Pittore Inglese

Collegio de’Marroniti

Roma

To J. Taylor Esqr

with a Dra[wi]ng of J. Keats & some hair

John Keats's lock of hair

John Keats, lock of hair cut by Joseph Severn, 1821. MA 214.8. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1909.

Small paper packet

Small paper packet that once held a lock of Keats’s hair, 1821. MA 214.8. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1909.

This Hair was cut

from Keats’s head as he

lay on his death bed by

his friend Joseph Severn.

"My name will not appear"

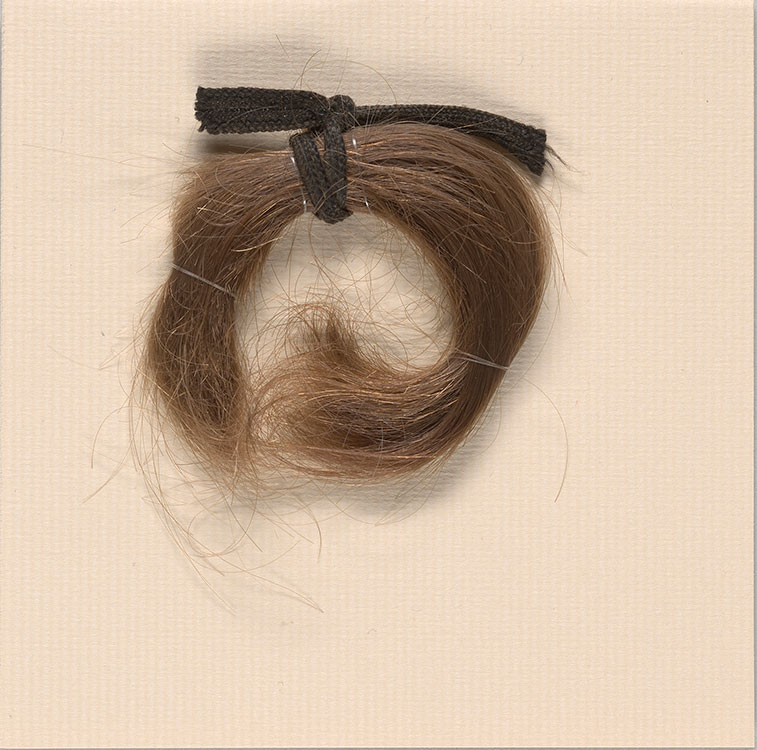

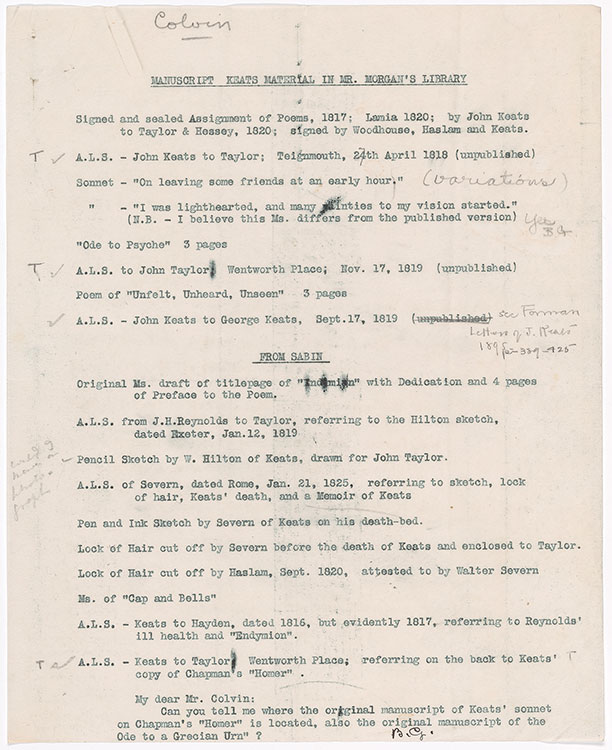

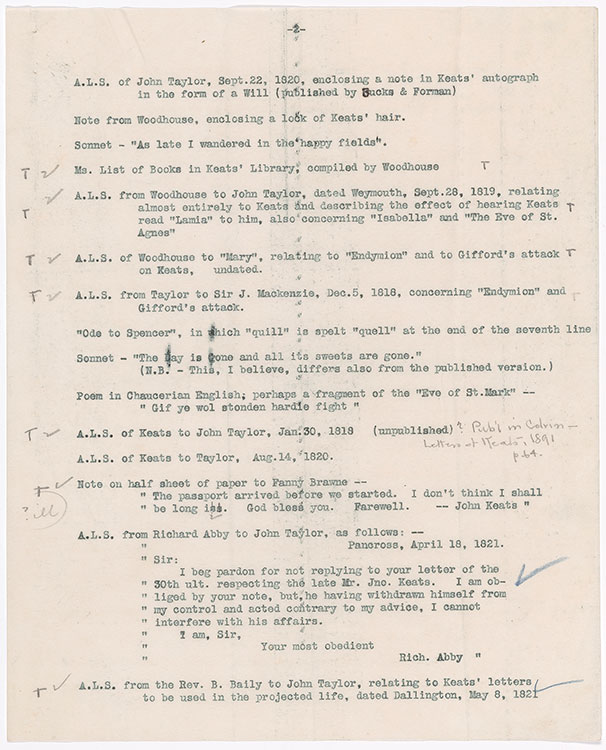

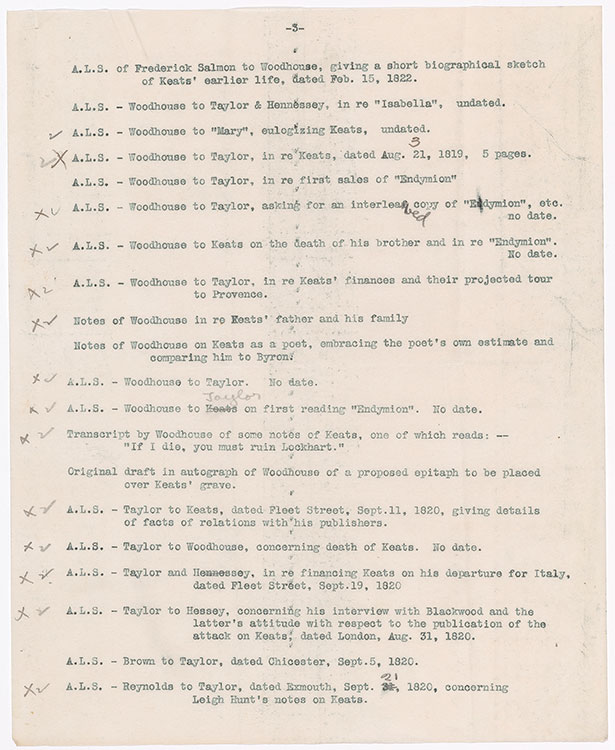

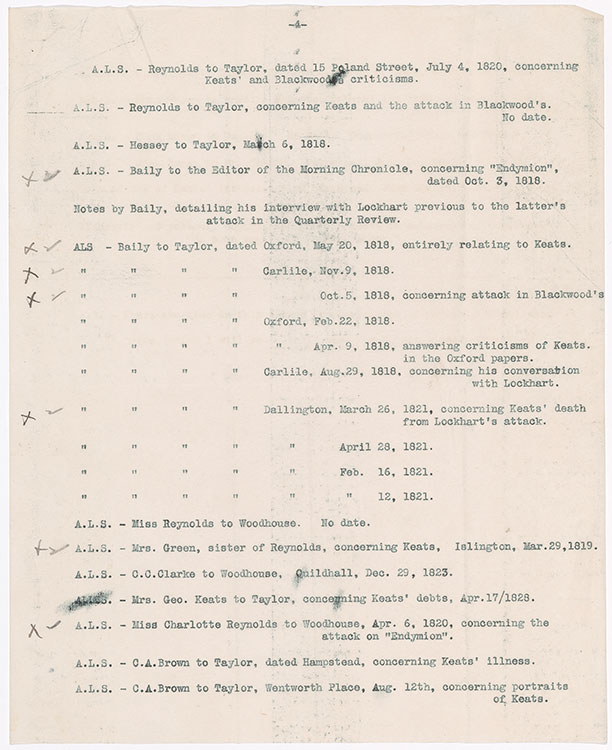

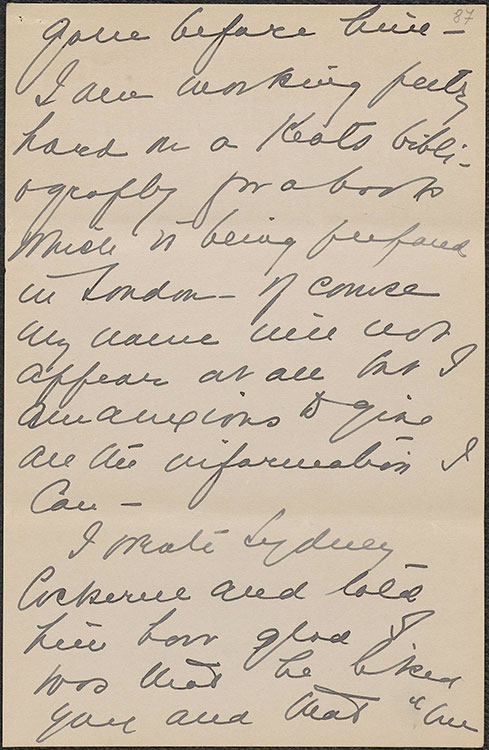

In 1912 Belle Greene compiled a typescript research guide to the Morgan’s Keats collection. The list includes most of the objects discussed in this exhibition, including the Severn sketch and lock of Keats’s hair. Greene described her project in a letter to the art historian Bernard Berenson (1865–1959), her romantic partner, friend, and colleague: “I am working pretty hard on a Keats bibliography for a book which is being prepared in London—of course my name will not appear at all but I am anxious to give all the information I can.” Greene drafted the list for Sidney Colvin (1845–1927), who was writing a new, comprehensive biography of Keats, published in 1917 as John Keats, his Life and Poetry, his Friends, Critics and After-Fame. Though Colvin does thank Greene briefly in his acknowledgments, her words stand as a reminder that scholarship is often advanced by the largely uncredited efforts of librarians.

In 1912 Belle Greene compiled a typescript research guide to the Morgan’s Keats collection. The list includes most of the objects discussed in this exhibition, including the Severn sketch and lock of Keats’s hair. Greene described her project in a letter to the art historian Bernard Berenson (1865–1959), her romantic partner, friend, and colleague: “I am working pretty hard on a Keats bibliography for a book which is being prepared in London—of course my name will not appear at all but I am anxious to give all the information I can.” Greene drafted the list for Sidney Colvin (1845–1927), who was writing a new, comprehensive biography of Keats, published in 1917 as John Keats, his Life and Poetry, his Friends, Critics and After-Fame. Though Colvin does thank Greene briefly in his acknowledgments, her words stand as a reminder that scholarship is often advanced by the largely uncredited efforts of librarians.

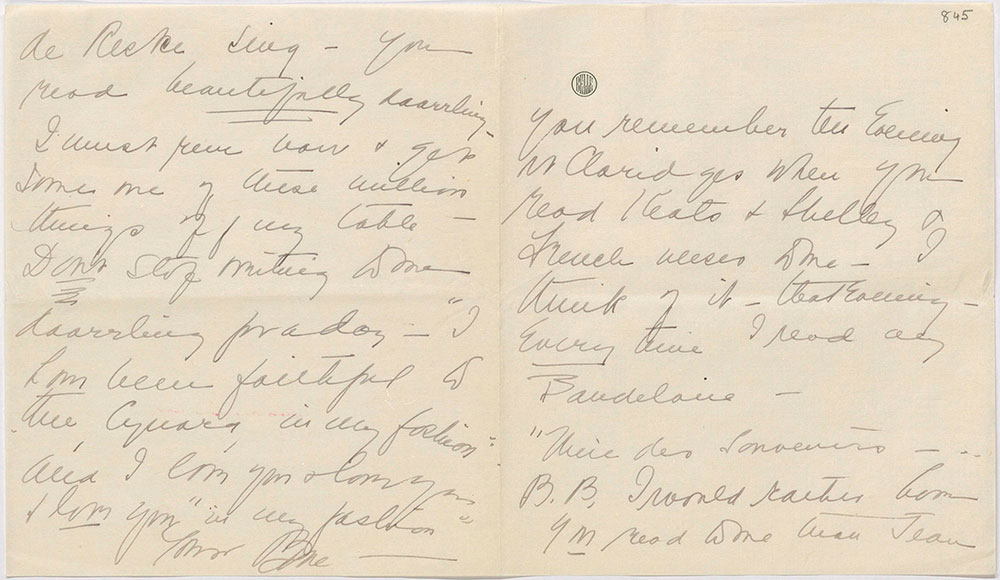

Greene’s letters to Berenson are preserved at I Tatti, the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies. The letters frequently reference Greene’s work at the Morgan, recounting acquisitions, describing collection research, and tracing her extensive professional networks. Another of these letters even touches upon her love of Keats’s poetry. Writing on 22 September 1911, Greene reminisces about her time spent with Berenson at Claridge’s Hotel, London: “you remember the Evening at Claridge’s when you read Keats + Shelley + French verses to me—I think of it—that evening—Every time I read any Baudelaire.” Another romantic interest of Greene’s, the publisher and gallery owner Mitchell Kennerly (1878–1950), also read Keats and Shelley to her, as recounted in a May 1914 letter to Berenson. A team at the Morgan is currently transcribing the entire archive of letters (616 in total) that Greene wrote to Berenson and has plans to make the images and transcriptions freely available online.

Belle da Costa Greene, “Manuscript Keats Material in Mr. Morgan’s Library,” typescript list with annotations by Greene and Sidney Colvin, 1912, p. 2. ARC 1310. Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum.

Manuscript Keats Material, p.1

Belle da Costa Greene, “Manuscript Keats Material in Mr. Morgan’s Library,” typescript list with annotations by Greene and Sidney Colvin, 1912, p. 1. ARC 1310. Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum.

Manuscript Keats Material, p.2

Belle da Costa Greene, “Manuscript Keats Material in Mr. Morgan’s Library,” typescript list with annotations by Greene and Sidney Colvin, 1912, p. 2. ARC 1310. Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum.

Manuscript Keats Material, p.3

Belle da Costa Greene, “Manuscript Keats Material in Mr. Morgan’s Library,” typescript list with annotations by Greene and Sidney Colvin, 1912, p. 3. ARC 1310. Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum.

Manuscript Keats Material, p.4

Belle da Costa Greene, “Manuscript Keats Material in Mr. Morgan’s Library,” typescript list with annotations by Greene and Sidney Colvin, 1912, p. 4. ARC 1310. Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum.

Manuscript Keats Material, p.5

Belle da Costa Greene, “Manuscript Keats Material in Mr. Morgan’s Library,” typescript list with annotations by Greene and Sidney Colvin, 1912, p. 5. ARC 1310. Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum.

Belle da Costa Greene letter to Bernard Berenson, 20 August 1912

Belle da Costa Greene, letter to Bernard Berenson, 20 August 1912, p. 11. Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers, Box 61, Folder 2. Biblioteca Berenson, I Tatti - The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies, courtesy of the President and Fellows of Harvard College.

gone before him—

I am working pretty

hard on a Keats bibli-

ography for a book

which is being prepared

in London—of course

my name will not

appear at all but I

am anxious to give

all the information I

Can—

I wrote Sydney

Cockerell and told

him how glad I

was that he liked

you and that “the

Belle da Costa Greene letter to Bernard Berenson, 22 September 1911

Belle da Costa Greene, letter to Bernard Berenson, 22 September 1911, pp. 19–20. Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers, Box 610 Folder 20. Biblioteca Berenson, I Tatti - The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies, courtesy of the President and Fellows of Harvard College.

[p. 19]

you remember the Evening

at Claridges when you

read Keats + Shelley +

French verses to me—I

think of it—that evening—

every time I read any

Baudelaire—

“Mère des souvenirs— .. 1

B.B. I would rather have

you read to me than Jean

[p. 20]

de Reske [sic] sing—you

read beautifully daarrling—

I must run now + get

some one of these million

things off my table—

Don’t stop writing to me

daarrling for a day—“I

have been faithful to

thee, Cynara, in my fashion.”2

And I love you + love you

+ love you “in my fashion”

Yours Belle—

- The opening phrase of Charles Baudelaire’s “Le Balcon” (The Balcony), from his Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil, 1857).

- Line from Ernest Dowson’s poem “Non sum qualis eram bonae sub regno Cynarae” (1896).

Belle da Costa Greene letter to Bernard Berenson, 5 May 1914

Belle da Costa Greene, letter to Bernard Berenson, 5 May 1914, p.8. Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers, Box 62, Folder 1. Biblioteca Berenson, I Tatti - The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies, courtesy of the President and Fellows of Harvard College.

hardly breathe for the joy of it–.

Kennerly came to the house for

dinner last night, just Mother

he + I as both the children were

dining out. He read to me

for several hours—Keats,

Shelley, and—Robert Bridges

whom he adores. Went to bed

quite early and had a horrid

dream about you—I must

send this off now too get it on

the K.W.II.

You must be sure to faithfully

report everything Agnes

says + does—Especially if

it is uncomplimentary to me!

It is so wonderful there, the

trees + grass + flowers, that

I know how far more

wonderful it must be in Florence—

Ever your devoted and

very loving

Belle

“Oh, weep for Adonais—he is dead!”

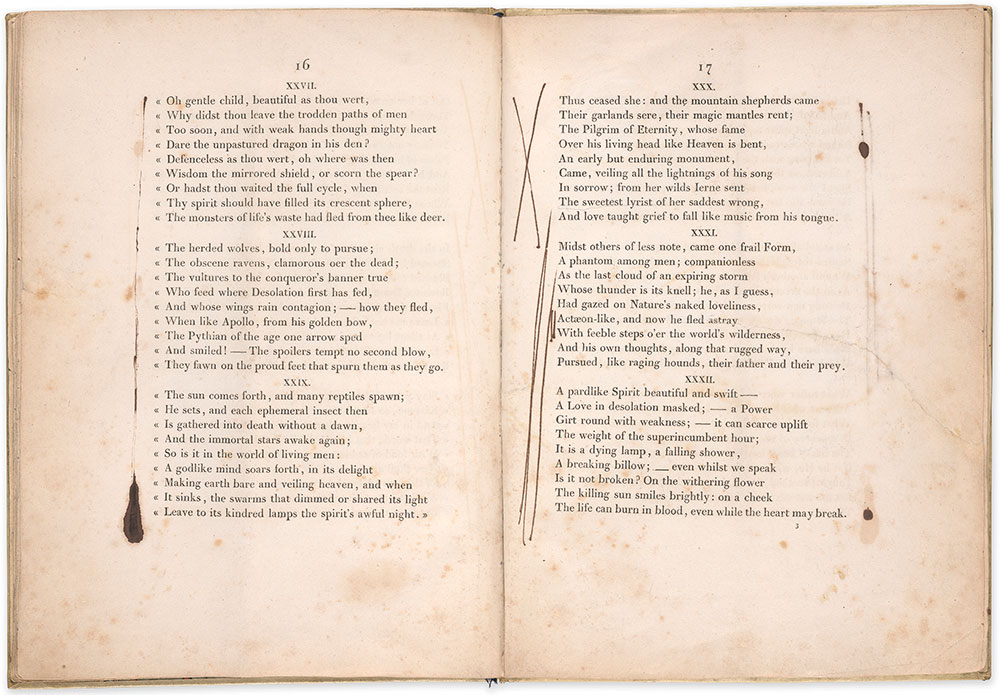

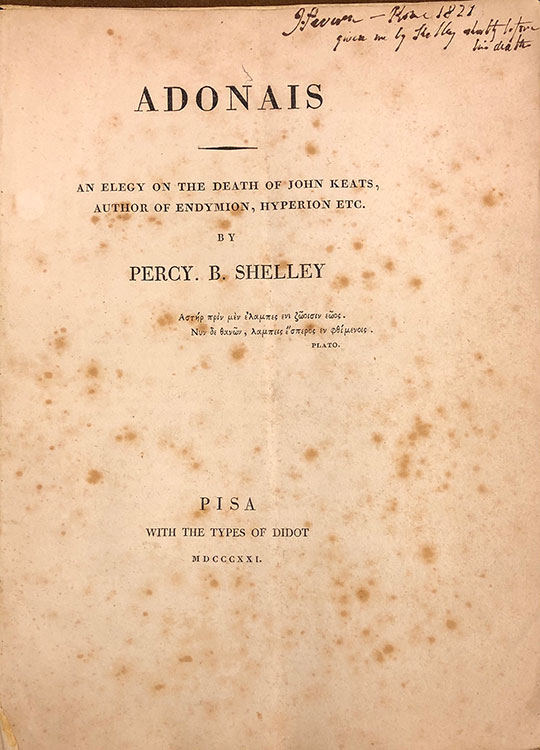

Soon after Keats’s death, Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote what is arguably the most famous literary elegy in English. Yet Adonais has done much to distort its subject’s reputation, characterizing Keats as exceedingly weak and fragile—as a “nursling,” a “gentle child,” a “pale flower” withered by bad reviews. Shelley reinforced these notions in his preface to Adonais, where he attributes Keats’s death to negative press directed at Endymion:

The savage criticism on his Endymion, which appeared in the Quarterly Review, produced the most violent effect on his susceptible mind; the agitation thus originated ended in the rupture of a blood-vessel in the lungs; a rapid consumption ensued, and the succeeding acknowledgments from more candid critics, of the true greatness of his powers, were ineffectual to heal the wound thus wantonly inflicted.

Shelley gave this copy of Adonais to Keats’s deathbed companion, Joseph Severn, as recorded in a handwritten note on the title page: “J. Severn— Rome 1821 given [to] me by Shelley shortly before his death.” Severn marked several passages in the volume, including those that imagine fellow poets Lord Byron (“The Pilgrim of Eternity”) and Shelley (“a pardlike Spirit beautiful and swift”) mourning Keats. Another marked passage draws attention to the critics allegedly responsible for Keats’s decline, here figured as “herded wolves” and “obscene ravens, clamorous o’er the dead.”

Shelley gave this copy of Adonais to Keats’s deathbed companion, Joseph Severn, as recorded in a handwritten note on the title page: “J. Severn— Rome 1821 given [to] me by Shelley shortly before his death.” Severn marked several passages in the volume, including those that imagine fellow poets Lord Byron (“The Pilgrim of Eternity”) and Shelley (“a pardlike Spirit beautiful and swift”) mourning Keats. Another marked passage draws attention to the critics allegedly responsible for Keats’s decline, here figured as “herded wolves” and “obscene ravens, clamorous o’er the dead.”

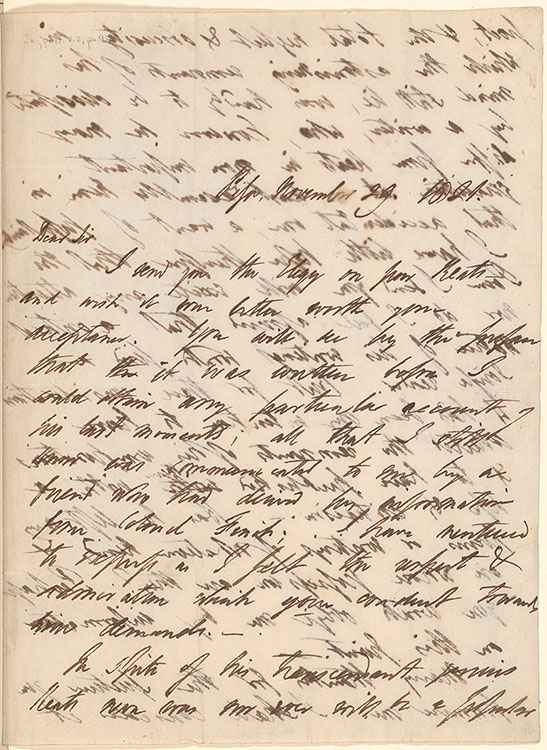

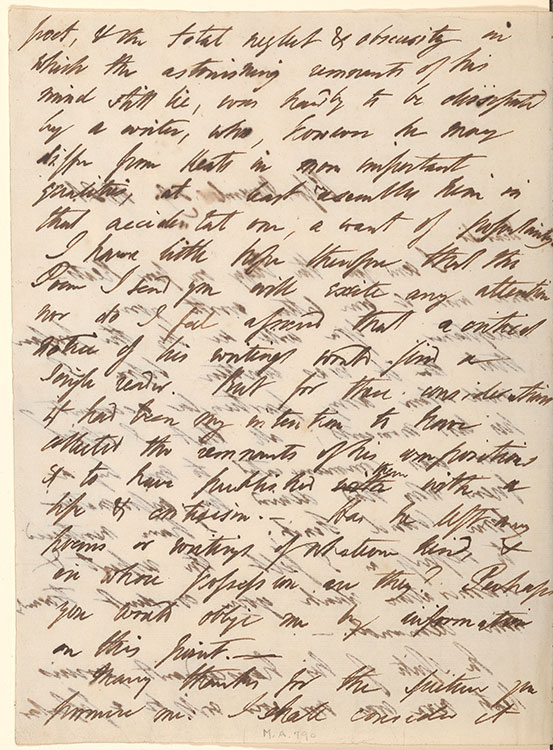

The Morgan additionally owns the letter Shelley sent Severn to accompany the volume. Undoubtedly with a dose of affected modesty, Shelley characterizes his “Elegy on poor Keats” as deficient, written “before [he] could attain any particular account of his [i.e., Keats’s] last moments.” He continues with a well-known pronouncement on the literary reputation of Keats; according to Shelley, neither poet will ever become popular:

In spite of his transcendent genius Keats never was nor ever will be a popular poet, & the total neglect & obscurity in which the astonishing remnants of his mind still lie, was hardly to be dissipated by a writer, who, however he may differ from Keats in more important qualities, at least resembles him in that accidental one, a want of popularity.

Shelley also speaks to a nascent interest in Keats’s literary remains, “the remnants of his compositions”: “Has he left any poems or writings of whatever kind, & in whose possession are they?” Despite Shelley’s prediction that Keats’s work will languish in “total neglect & obscurity,” interest in his life and poetry would only increase over the nineteenth century, culminating in the first major scholarly work on the poet, Richard Monckton Milnes’s Life, Letters and Literary Remains of John Keats (1848).

Percy Bysshe Shelley, Adonais: An Elegy on the Death of John Keats, Author of “Endymion,” “Hyperion” Etc. Pisa: with the types of Didot, 1821, pp. 16–17. PML 20023. Purchased by Belle da Costa Greene on behalf of J. P. Morgan, Jr., 1915.

Percy Bysshe Shelley letter to Joseph Severn, p.1

Percy Bysshe Shelley, letter to Joseph Severn, 29 November 1821, p. 1. MA 790.2. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1911.

p. 1

Pisa, November 29. 1821

Dear Sir

I send you the Elegy on poor Keats

and wish it was better worth your

acceptance. You will see by the preface

that the it was written before I

could attain any particular account of

his last moments; all that I still

know was communicated to me by a

friend who had derived his information

from Colonel Finch; I have ventured

to express as I felt the respect &

admiration which your conduct towards

him demands.—

In spite of his transcendent genius

Keats never was nor ever will be a popular

Percy Bysshe Shelley letter to Joseph Severn, p.2

Percy Bysshe Shelley, letter to Joseph Severn, 29 November 1821, p. 2. MA 790.2. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1911.

p. 2

poet, & the total neglect & obscurity in

which the astonishing remnants of his

mind still lie, was hardly to be dissipated

by a writer, who, however he may

differ from Keats in more important

qualities, at least resembles him in

that accidental one, a want of popularity.

I have little hope therefore that the

Poem I sent you will excite any attention

nor do I feel assured that a critical

notice of his writings would find a

single reader. But for these considerations

it had been my intention to have

collected the remnants of his compositions

& to have published with them with a

life & criticism.– Has he left any

poems or writings of whatever kind, &

in whose possession are they? Perhaps

you would oblige me by information

on this point.—

Many thanks for the picture you

promise me: I shall consider it

Percy Bysshe Shelley letter to Joseph Severn, p.3

Percy Bysshe Shelley, letter to Joseph Severn, 29 November 1821, p. 3. MA 790.2. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1911.

p. 3

among the most sacred relics of the past.

For my part, I little expected when

I last saw Keats at my friend Leigh

Hunts’, that I should survive him.—

Should you ever pass through Pisa

I hope to have the pleasure of seeing

you, & of cultivating an acquaintance

into something pleasant begun under

such melancholy auspices.—

Accept my dear sir the assurances

of my sincere esteem, & believe

me

Your most sincere & faithful ser[vant].

Percy B. Shelley

Do you know Leigh Hunt? I expect

him & his family here every day.

Building the Morgan's Keats collection

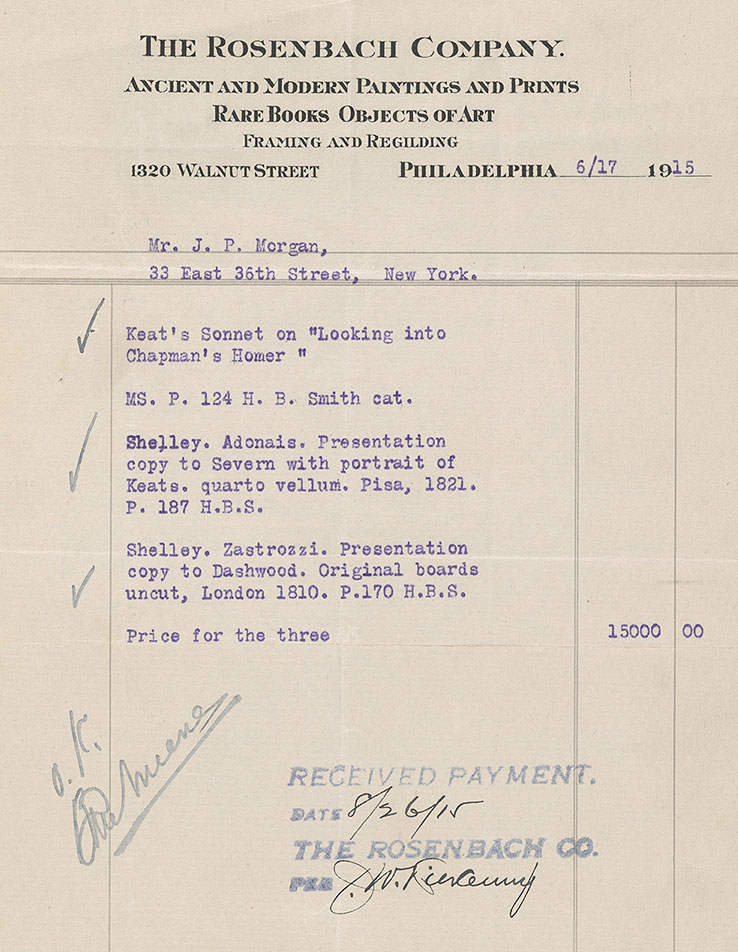

After J. Pierpont Morgan’s death in 1913, Greene continued to make major acquisitions on behalf of his son and heir, J. P. Morgan, Jr. In the summer of 1915 she purchased two important Keats items from the Philadelphia bookseller A. S. W. Rosenbach (1876–1952): an early manuscript of Keats’s sonnet “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer” and the copy of Shelley’s Adonais given to Joseph Severn. The surviving invoice shows that she paid $15,000 for these two items as well a copy of Shelley’s Zastrozzi.

“On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer” is the most celebrated of Keats’s early poems, composed and published in the fall of 1816. The story goes that Keats and his friend Charles Cowden Clarke (1787–1877) stayed up all night reading George Chapman’s translation of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey (1616). The next morning Keats rapidly composed a sonnet on his transformative reading experience, likening it to the discovery of new planets or Europeans’ first glimpse at the Pacific Ocean’s eastern shore. After finishing the poem he promptly sent it back to Clarke, who was able to read it while eating breakfast.

Though scholars have long thought that the manuscript preserved at Harvard University’s Houghton Library is the original sent to Clarke, recent work has convincingly shown that the Harvard manuscript was sent instead to Joseph Severn; the original manuscript sent to Clarke, it seems, is now lost. The Morgan manuscript of “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer” is in Keats’s hand and was given to his friend John Hamilton Reynolds (1794–1852), who later inscribed it to his sister, “To Mariane Reynolds.” We can date the text of the Morgan manuscript as later than the Harvard copy, but earlier than the authoritative version published in Keats’s 1817 Poems. The Morgan manuscript’s “Yet could I never judge what Men could mean” in line 7 would become “Yet never did I breathe its pure serene” in the 1817 Poems, while the Harvard manuscript’s “wond’ring eyes” becomes “eagle eyes” in the Morgan copy (and “eagle eyes” would remain in later versions).

Invoice from The Rosenbach Company, 17 June 1915. ARC 1310. Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum.

On First Looking into Chapman's Homer

John Keats, “On Looking into Chapman’s Homer,” autograph manuscript, 1816. MA 214.3. Purchased by Belle da Costa Greene on behalf of J. P. Morgan, Jr., 1915.

To Mariane Reynolds —

Much have I travell’d in the Realms of gold

And many goodly states and kingdoms seen

Round many western islands have I been

Which Bards in featly to Apollo hold

Oft of one wide expanse had I been told

That deep brow’d Homer rules as his Demesne

Yet could I never judge what Men could mean

Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold

Then felt I like one Watcher of the Skies

When a new Planet swims into his Ken

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He star’d at the Pacific and all his men

Look at each other with a wild surmise

Silent upon a Peak in Darien.

Belle da Costa Greene letter to Sidney Colvin

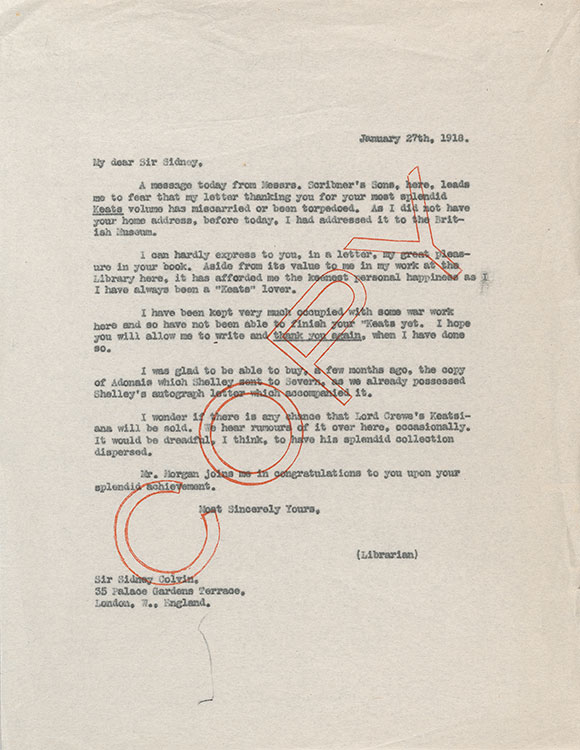

Though we do not have any commentary from Belle Greene about “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer,” she does mention her purchase of Severn’s copy of Adonais. In a letter to Sidney Colvin offering congratulations for his 1917 Keats biography, Greene describes herself as a “'Keats' lover” and mentions purchasing Severn’s Adonais: “I was glad to be able to buy, a few months ago, the copy of Adonais which Shelley sent to Severn, as we already possessed Shelley’s autograph letter which accompanied it.” Greene’s acquisition effectively reunited the two objects, showing once again her deep knowledge of the collection and keen sense for how to develop its various strengths.

Of course, there were Keats manuscripts Greene was not able to secure for the Library. J. Pierpont Morgan declined a set of letters offered in 1911 by the bookseller George H. Richmond; in a letter to A.J. Bowden, her contact at the firm, Greene expressed her disappointment that they were unable to make the acquisition: “I rather regret this, as I hoped we would wish to have them.” Again in 1912 Morgan declined a Keats letter, written to his brothers George and Tom in 1818, this time offered by the Minneapolis bookdealer Edmund D. Brooks. In her letter declining the offer Greene wrote, “I regret to say that Mr. Morgan is at present in a state of mind where he refuses to buy anything, and, for that reason, I cannot consider the purchase of your Keats letter. I think it extremely interesting and am sorry I cannot add it to this collection.”

But in other instances Greene and Morgan worked in lockstep, as in the case of their relationship with the writer and collector Annie Fields (1834–1915). Widow of the prominent publisher James T. Fields (1817–1881) and an important supporter of women writers in Boston, Annie Fields struck up a friendship with Belle Greene and Morgan and eventually offered her album of autograph poetry to the Library in 1909. In a 1910 letter Greene assures Fields that her “Book of Manuscripts … will have the place d’honneur in this Library, which I trust will last for all time.” The album included a fragment of Keats’s long narrative poem "Hyperion", the rest of which is held at the British Library.

Belle da Costa Greene, retained copy of typed letter to Sidney Colvin, 27 January 1918. ARC 1310. Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum.

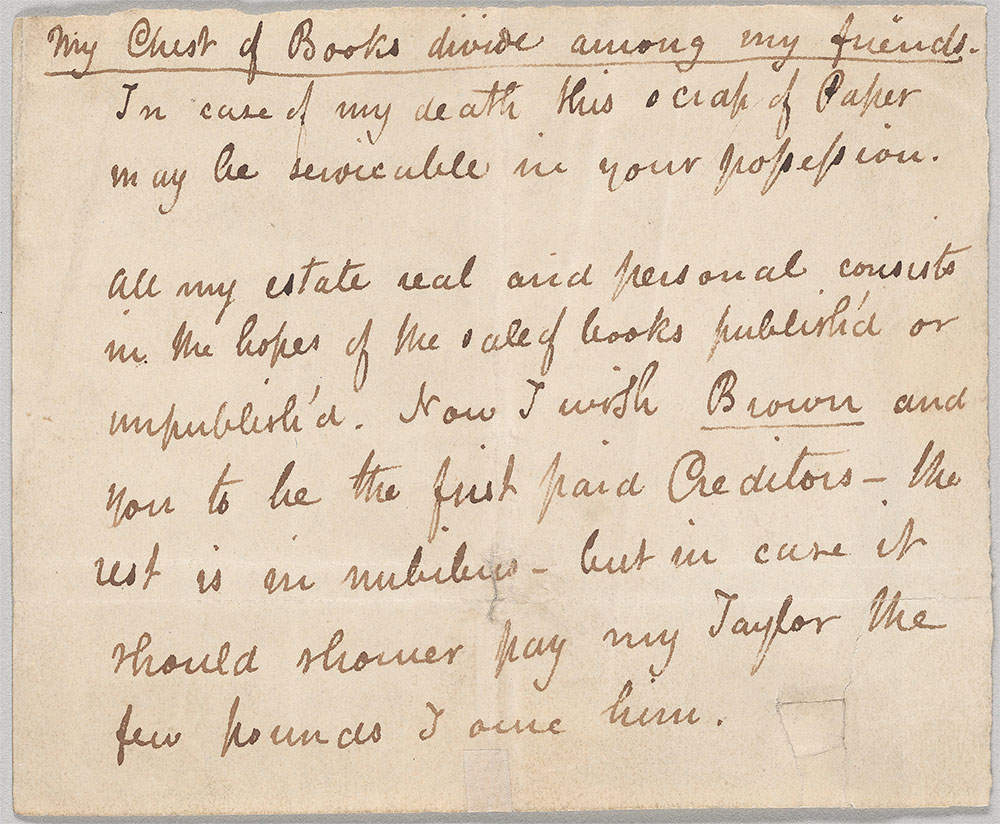

"My chest of books divide among my friends"

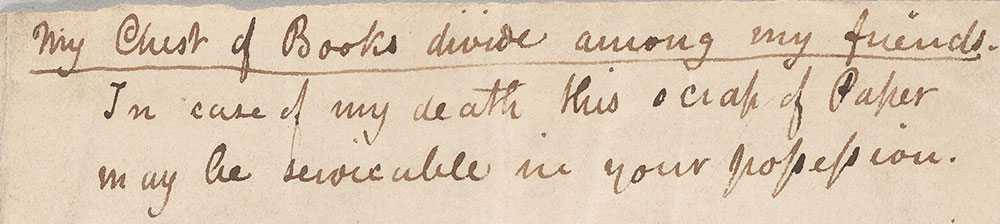

Before leaving for Italy in 1820, Keats made arrangements “in case of [his] death” and sent this unofficial will to his publisher John Taylor:

My Chest of Books divide among my friends.

In case of my death this scrap of Paper

may be servicable [sic] in your possession.

All my estate real and personal consists

in the hopes of the sale of books publish’d or

unpublish’d. Now I wish Brown and

you to be the first paid Creditors—the

rest is in nubilus—but in case it

should shower pay my Taylor the

few pounds I owe him.

Though owed an inheritance unfairly withheld for years, at the end of his life Keats was afflicted by poverty, with only a small library and “the hopes of the sale of books” to his name. Written in iambic pentameter, “My chest of books divide among my friends” would prove to be his last line of verse.

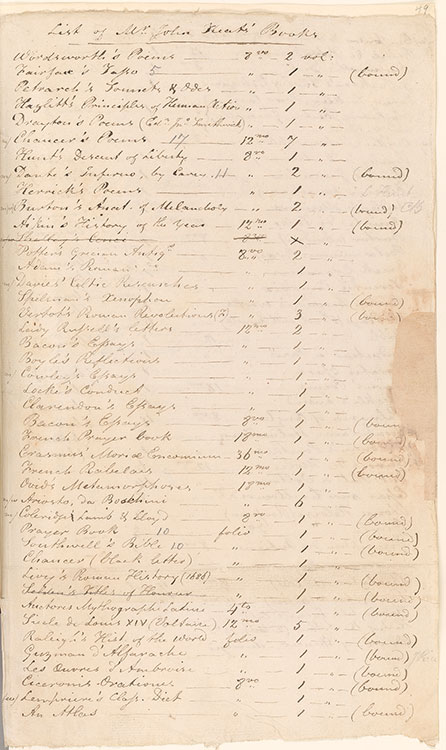

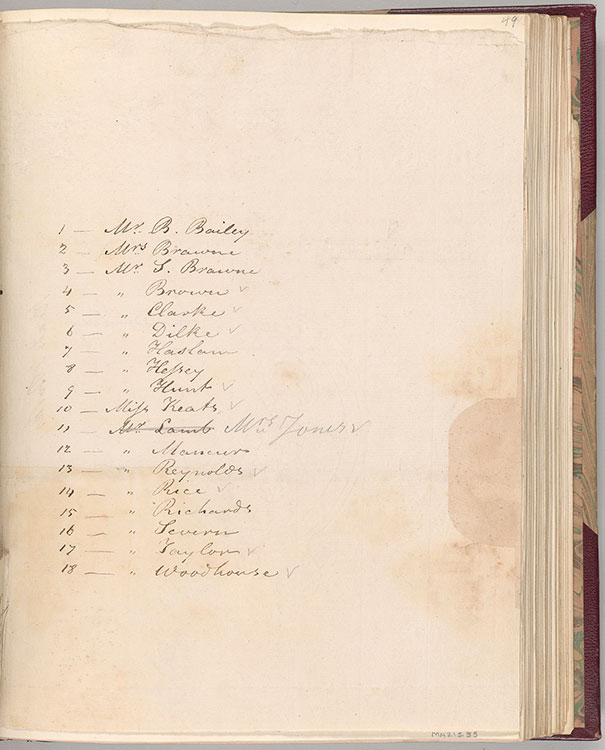

To help execute the will’s terms, his former roommate and sometime traveling companion Charles Armitage Brown drafted a catalogue of Keats’s library and the names of friends who had lent or given books to the poet. The list includes volumes of Keats’s favorite writers—Dante, Spenser, and Shakespeare—along with literary works by Wordsworth, Tasso, Petrarch, Chaucer, Bacon, Erasmus, Rabelais, and Ben Jonson, as well as standard classical texts like Horace and Terence along with outliers such as “Fencing Familiarized.” (Keats, however, was known for his pugnacity as a young man and enjoyed boxing.) His multi-volume sets of Shakespeare and Spenser—missing their sixth and final five volumes, respectively—are preserved at the Houghton Library of Harvard University.

The list is bound within a volume of letters, transcriptions, and documents compiled by Richard Woodhouse (1788–1834), a lawyer who worked with Keats’s publisher John Taylor and helped edit his poems for print. Woodhouse was also the first Keats collector, not only gathering letters and documents written by friends of the poet but also assembling literary manuscripts and transcribing his poems, in some cases from now-lost original sources. The Woodhouse collection at the Morgan includes copies of several well-known Keats poems, including “Day is gone, and all its sweets are gone” and “Isabella: or, the Pot of Basil,” which is transcribed in shorthand.

John Keats's will, recto

John Keats, unofficial will, autograph manuscript, 1820, recto. MA 214.2. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1909.

My Chest of Books divide among my friends.

In case of my death this scrap of Paper

may be servicable [sic] in your possession.

All my estate real and personal consists

in the hopes of the sale of books publish’d or

unpublish’d. Now I wish Brown and

you to be the first paid Creditors—the

rest is in nubilus—but in case it

should shower pay my Taylor the

few pounds I owe him.

John Keats's will, verso

John Keats, unofficial will, autograph manuscript, 1820, verso (in the hand of John Taylor). MA 214.2. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1909

[in the hand of John Taylor]

NB On the 14th of August or the 15th

1820 I received this paper which

is in John Keats’s Handwriting

inclosed in the annexed letter

which came by the 3dy Post

22 Sept 1820 John Taylor

List of John Keats's books, p.1

Charles Armitage Brown, “List of Mr. John Keats’ Books,” autograph manuscript, July 1821, p. 1. MA 215.55. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1906.

p. 1

List of Mr John Keats’ [sic] Books1

Wordsworth’s Poems

Fairfax’s Tasso

Petrarch’s Sonnets & Odes

Hazlitt’s Principles of Human Action

Drayton’s Poems (Ed[itio]n Jo[h]n Smethwick)

Chaucer’s Poems

Hunt’s Descent of Liberty

Dante’s Inferno, by Carey

Herrick’s Poems

Burton’s Anat[omy] of Melancholy

Aikin’s History of the Year

Shelley’s Cenci

Potter’s Grecian Antiq[uitie]s

Adam’s Roman [Antiquities]

Davies’ Celtic Researches

Spelman’s Xenophon

Vertot’s Roman Revolutions (F[rench])

Lady Russell’s letters

Bacon’s Essays

Boyle’s Reflections

Cowley’s Essays

Locke’s Conduct

Clarendon’s Essays

Bacon’s Essays

French Prayer book

Erasmus’ Moriae Encomium [Praise of Folly]

French Rabelais

Ovid’s Metamorphoses

Ariosto, da Boschini

Coleridge Lamb & Lloyd

Prayer Book

Southwell’s Bible

Chaucer (black letter)

Livy’s Roman History (1686)

Selden’s Titles of Honour

Auctores Mythographi Latini [Latin Mythographic Authors]

Siecle de Louis XIV (Voltaire) [Century of Louis XIV]

Raleigh’s Hist[ory] of the World

Guzman d’Alfarache

Les Ouvres d’Ambroise [Works of Ambrose]

Ciceronis Orationes [Orations of Cicero]

Lempriere’s Class[ical] Dict[ionary]

An Atlas

1. This transcription includes the titles of books, with editorial expansions and title translations indicated by brackets. The transcription does not include information about format or the number of volumes, nor does it reproduce the “m” and “w” letters added by Brown to certain entries.

List of John Keats's books, p.2

Charles Armitage Brown, “List of Mr. John Keats’ Books,” autograph manuscript, July 1821, p. 2. MA 215.55. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1906

p. 2

Ben Jonson & Beaumont & Fletcher

Rime di Petrarca [Petrarch’s Verses]

Ainsworth’s Dict[ionary]

Z. Jackson’s Illus[tration]s of Shakespear[e]

Carew, Suckling, Prior, Congreve, Blackmore, Fenton, Granville, and Yalden

Ovidii Metamorphoseon [Ovid’s Metamorphoses]

Bailey’s Dictionary

Hunt’s Juvenilia

Fencing familiarized

Dudley’s Memoirs

Aminta di Tasso [Tasso’s Aminta]

Burton (abridged)

Poetae minores Graeci [Minor Greek Poets]

Greek Grammar

Terentii Comoediae [Terence’s Comedies]

Bishop Beveridge’s Works

Old Plays (5th vol. with Reynolds)

Bible

Conducteur à Paris [Driver in Paris]

Horatii Opera [Horace’s Works]

Burns’ Poems

Mickle’s Lusiad

Palmerin of England

Vocabulaire Italien-Franç [French-Italian Vocabulary]

Baldwin’s Pantheon

Ouvres de Moliere [Moliere’s Works]

Dict[ionnaire] Phil[osophique] de Voltaire [Voltaire’s Philosophical Dictionary]

Essai sur les Moeurs de [Voltaire] [Voltaire’s Essay on Manners]

Nouv[eau] Heloïse (Rousseau) [New Heloise]

Emile

Description des Antiques [Description of the Ancients]

Spectator—(1st lost)

Shakespear[e] (6th lost)

Marmontel’s Incas

Hist[ory] of K[ing] Arthur (2nd lost)

Odd vol. of Spencer,—damaged

List of John Keats's books, p.3

Charles Armitage Brown, “List of Mr. John Keats’ Books,” autograph manuscript, July 1821, p. 3. MA 215.55. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1906.

p. 3

1—Mr B. Bailey

2—Mrs Brawne

3—Mr S. Brawne

4—[Mr] Brown

5—[Mr] Clarke

6—[Mr] Dilke

7—[Mr] Haslam

8—[Mr] Hessey

9—[Mr] Hunt

10—Miss Keats

11—Mr Lamb Mrs Jones

12—[Mr] Mancur

13—[Mr] Reynolds

14—[Mr] Rice

15—[Mr] Richards

16—[Mr] Severn

17—[Mr] Taylor

18—[Mr] Woodhouse

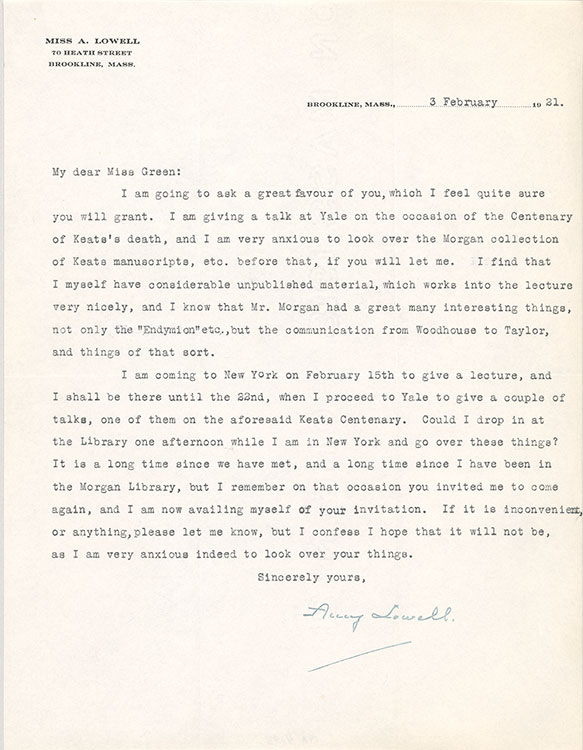

Amy Lowell, Keats Collector

In February 1921, the Boston poet Amy Lowell (1874–1925)—Greene’s friend and the preeminent American collector of Keatsiana—was due to give a talk at Yale to mark the centenary of Keats’s death. In preparation for her talk, she contacted Belle Greene on February 3 to arrange a visit to the Library, where she wished to consult “not only the ‘Endymion’ etc., but the communication from Woodhouse to Taylor, and things of that sort.” At the time Lowell was working on a major new biography of John Keats, which for the first time drew prominently on manuscript material in American collections, primarily her own and Morgan’s. (Lowell would leave her collection to Harvard, which now holds the largest collection of Keats manuscripts in the world.) Though Sidney Colvin had briefly touched upon items at the Morgan for his 1917 Keats biography, Amy Lowell would be the first scholar to seriously study this material. Her knowledge of the collection’s depth—which, as she recognized, extended well beyond the famous Endymion manuscript—is emblematic of her meticulous research into archival sources about Keats.

Amy Lowell, typed letter to Belle da Costa Greene, 3 February 1921. MA 4098. Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum.

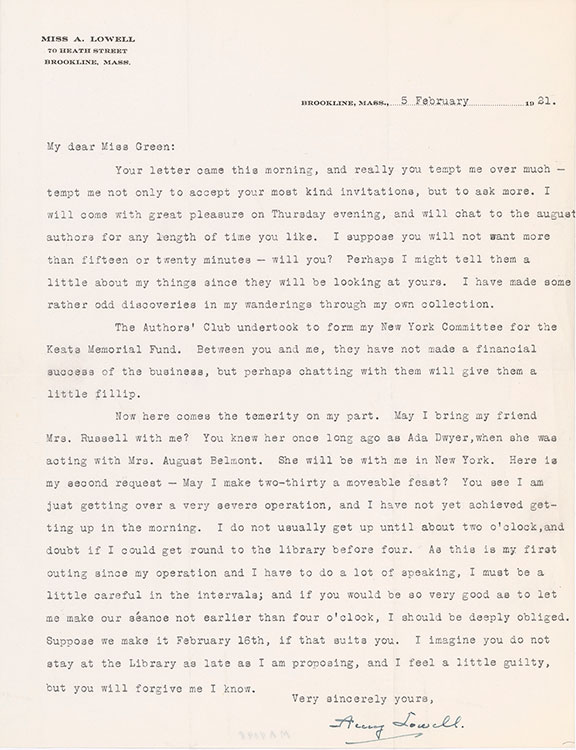

Amy Lowell letter to Belle da Costa Greene, 5 February 1921

Writing again on February 5th, Lowell began to make arrangements for a research trip while also accepting Greene’s invitation to address the Authors Club of New York at a private event in the Library. Greene was planning a display of Morgan materials to accompany Lowell’s “talk,” though, in another letter dated February 11th, Lowell playfully requests she refer to it using a different word: “For Goodness Sake, do not call it my ‘Talk.’ I thought it was to be a little sort of a chat —an informal bit of a thing.” These letters also allude to Lowell’s romantic partner, the actress Ada Dwyer Russell (1863–1952), whom she planned to bring along on her visit to the Library. Lowell’s two-volume John Keats would appear in 1925 with a dedication to Russell, the first and only publication Lowell dared dedicate to her life partner: “To A.D.R. This, and all my books A.L.”

Amy Lowell, typed letter to Belle da Costa Greene, 5 February 1921. MA 4098. Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum.

Amy Lowell letter to Belle da Costa Greene, 11 February 1921

Amy Lowell, typed letter to Belle da Costa Greene, 11 February 1921. MA 4098. Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum.

Amy Lowell letter to Belle da Costa Greene, 23 November 1921

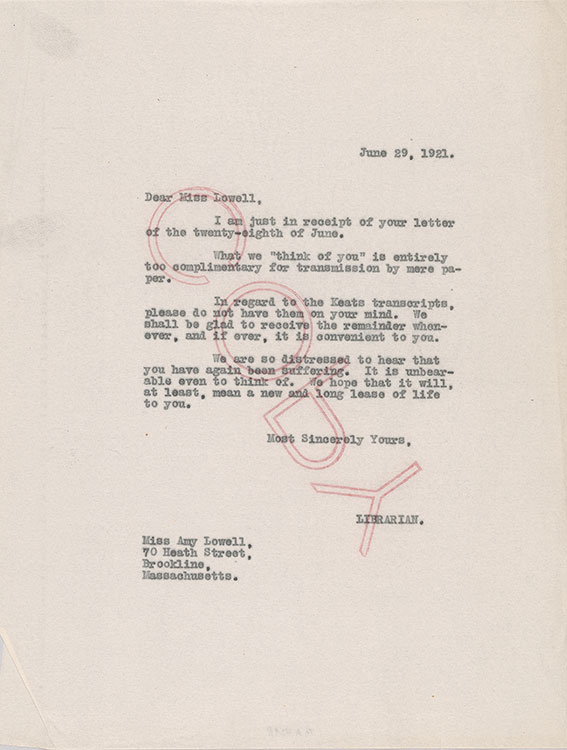

Lowell was the first scholar to study the “Woodhouse Book,” the bound compilation of letters, documents, and transcribed poetry assembled by the collector, lawyer, and Keats contemporary Richard Woodhouse. Lowell’s book on Keats explores various objects within the volume, including the library catalogue drawn up by Charles Armitage Brown along with unpublished letters between Woodhouse and Keats’s publisher John Taylor. In an age when the photographic reproduction of special collections material was hardly widespread, Lowell’s research necessitated several trips to New York to consult the manuscript. At one point she even sent Greene a “'cheeky' request” to consult the volume overnight in her hotel room while recovering from surgery. Greene agreed to the unconventional arrangement, humoring a friend and trusted colleague whom she clearly admired: in a letter from June 1921, Greene wrote, “What we ‘think of you’ is entirely too complimentary for transmission by mere paper."

Amy Lowell, typed letter to Belle da Costa Greene, 23 November 1921. MA 4098. Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum.

Belle da Costa Greene letter to Amy Lowell, 29 June 1921

Belle da Costa Greene, retained copy of typed letter to Amy Lowell, 29 June 1921. MA 4098. Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum.

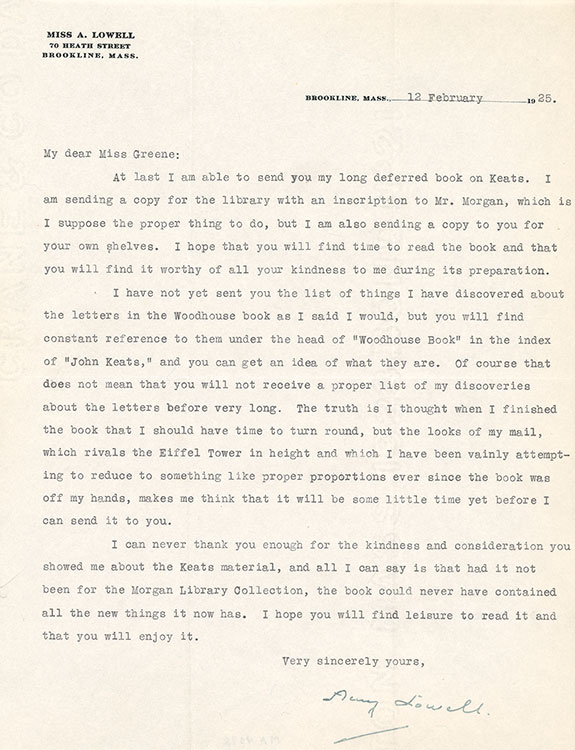

Amy Lowell letter to Belle da Costa Greene, 12 February 1925

In February 1925 Lowell completed her book and sent a copy to Greene, inscribing it “Belle da Costa Greene, with the grateful regards of Amy Lowell.” Lowell’s preface acknowledges the importance of private collections to her research, giving pride of place to the Morgan:

To Mr. J.P. Morgan of New York, owner of the Morgan Library, which he has just formally put at the service of students, but which has in fact always been at their service, assisted by the expert advice of its remarkable librarian, Miss Belle da Costa Greene, I am deeply obliged. Through Miss Greene’s kindness I have had free access to the Library for the past four years, and have been permitted to make such transcripts of manuscripts as I needed.

In a letter accompanying the gifted volumes (one for the Morgan’s reference collection, one for Greene), Lowell expands her thanks:

I can never thank you enough for the kindness and consideration you showed me about the Keats material, and all I can say is that had it not been for the Morgan Library Collection, the book could never have contained all the new things it now has. I hope you will find leisure to read it and that you will enjoy it.

Greene’s response is warm and grateful:

You have simply overwhelmed me in presenting me (personally) with a copy of your “John Keats”. I had stupidly thought to wait until I was able to read every word of it, before writing you—but I find myself continuously going back and re-reading portions of especial interest and importance to me—and so have not yet finished Volume One! And I feel that I cannot allow any further time to elapse before I thank you, truly from my heart, for both your wonderful mention of me in your preface and for the gift of this really great book.—which will always remain one of my most treasured possessions.

Amy Lowell would tragically die a few months later, in May 1925, but her John Keats has endured as one of the most important early twentieth-century biographies of the poet. The copy she gave Belle Greene sits on the shelves of the Morgan’s reference collection today.

Amy Lowell, typed letter to Belle da Costa Greene, 12 February 1925. MA 4098. Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum.

Exhibiting Keats

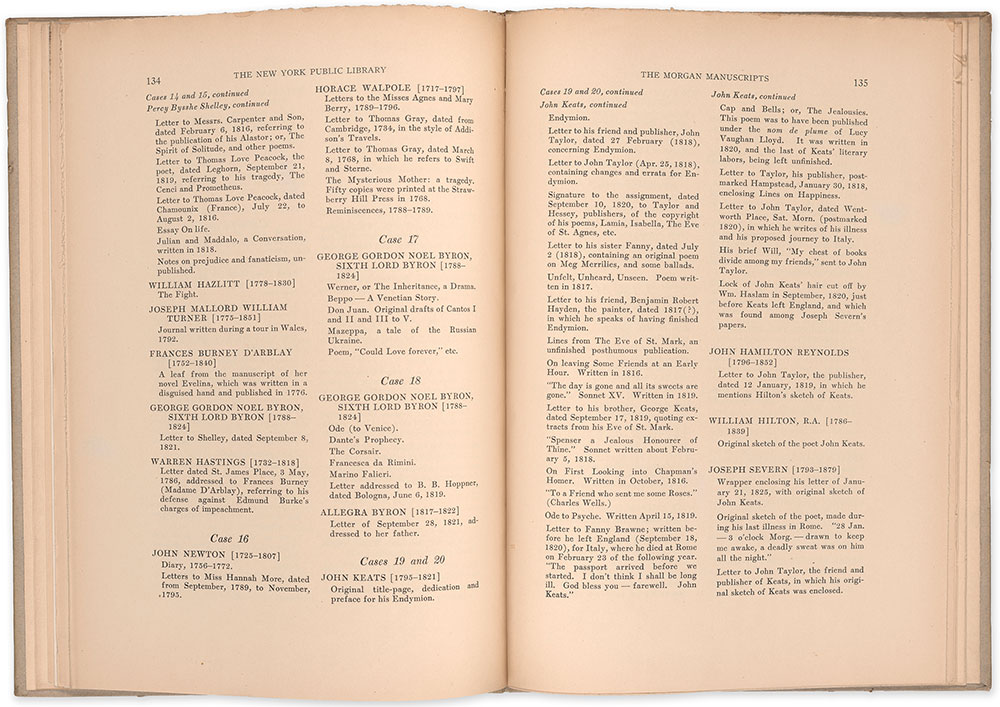

Greene became the Morgan’s first director in 1924, when J. P. Morgan, Jr., established the library as a public institution. Before the Morgan’s gallery space was completed in 1926, Greene and her staff mounted exhibitions at the New York Public Library, for whom Mr. Morgan served as a trustee and Vice President. Following a successful NYPL exhibition of the Morgan’s American historical manuscripts in the spring of 1924, Original Manuscripts and Drawings of English Authors from the Pierpont Morgan Library opened in December 1924 and closed the following April, attracting around 180,000 visitors to see over 300 collection items—at the time the largest exhibition of manuscripts in American history. Belle Greene put on view twenty-seven objects by or related to Keats, one of the best-represented authors on display, and included nearly every Keats artifact from the present exhibition. A catalogue of the exhibition was printed privately but also reprinted in the New York Library Bulletin of March 1925.

Edmund Lester Pearson, “The Morgan Manuscripts,” Bulletin of the New York Public Library, Volume 29, Number 3 (1925). Ref 913 P3. Morgan Library Reference Collection.

E.H. Anderson letter to Belle da Costa Greene, 10 July 1924

The Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum hold correspondence between Greene and colleagues at NYPL that provide additional details about the planning of Original Manuscripts and Drawings of English Authors from the Pierpont Morgan Library. A letter to Greene from Director E.H. Anderson, dated July 10, 1924, responds to her query about mounting a “large, important, and really interesting Exhibition of English Literary and Historical Autograph Manuscripts” in NYPL’s exhibition space. Citing the requisite consent of NYPL’s Executive Committee, Anderson assures Greene “there will be no difficulty in securing their hearty approval.”

E.H. Anderson, typed letter to Belle da Costa Greene, 10 July 1924. ARC 1310. Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum.

Belle da Costa Greene letter to H.M. Lydenberg, 15 November 1924

Greene proceeds to correspond with H.M. Lydenberg, Reference Librarian at NYPL, about various exhibition matters including the checklist, labels, opening and closing dates, and even a promotional poster. In reviewing a proof of the poster, which apparently sported “The Pierpont Morgan Library” in rather large lettering, Greene writes, “We really are not as conceited as we seem, so that I think it would be better to have the first 2 lines of ‘Original Manuscripts and Drawings of English Authors’ in somewhat larger type, so that the words ‘The Pierpont Morgan Library’ will not stand out so prominently.” From institutional negotiations and checklist development to label writing and promotional materials, Belle Greene was deeply involved in every aspect of the Morgan’s first exhibition of literary manuscripts.

Belle da Costa Greene, retained copy of typed letter to H.M. Lydenberg, 15 November 1924. ARC 1310. Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum.

Mary P. Parsons letter to Belle da Costa Greene, 11 February 1921

Three years earlier, in February 1921, the world commemorated the 100th anniversary of Keats’s death. Though there was no display marking this occasion at the Library, Belle Greene entertained numerous requests for loans or photography of the Morgan’s Keats collection for various centenary exhibitions. The Librarian of the Morristown Library, Mary P. Parsons, wrote Greene to request photography of a few holdings from the Morgan for inclusion in a Keats exhibition scheduled for February 23rd. The largest centenary show took place at Harvard, which featured rarely or never-before-displayed manuscripts from the two important private Keats collections in America, owned by Amy Lowell and J.P. Morgan, Jr. Correspondence with Harvard in the Morgan Archives documents the list of objects on loan for this exhibition, including the two Keats letters acquired by Greene early in her career, “Ode to Psyche,” the sonnet on Fanny Brawne titled “The day is gone and all its sweets are gone!”, and Shelley’s letter presenting Adonais to Joseph Severn.

Through her acumen in collection development, her collaborative work with scholars, and her efforts at outreach and exhibition design, Belle Greene played an instrumental role in making the Morgan’s Keats collection one of the best known in the world.

Mary P. Parsons, typed letter to Belle da Costa Greene, 11 February 1921. ARC 1310. Archives of the Morgan Library & Museum .

Conclusion: Scraps of Words Written in Fire

Nothing but paper passed along with the breath

of its words alive with fire. Scraps of paper,

scraps of words written in fire.

—Stanley Plumly, Posthumous Keats: A Personal Biography (2008), p. 364.

Stanley Plumly’s meditation on the ephemerality of Keats’s poetry manuscripts—their miraculous survival in the face of oblivion—speaks to a theme of profound relevance to the story of Belle Greene’s Keats. Going back to the February 1818 letter and Keats’s first poetic axiom—“poetry … should strike the Reader as a wording of his own highest thoughts, and appear almost a Remembrance”—it is vital to stress the almost in “almost a remembrance.” On one hand it captures the idea of poetry as authentic imaginative expression. But the word equally signals a partial remembering, a half memory, and this idea is borne out in the extant archives, riddled with gaps, that we must rely on to tell the stories of Keats and Greene.

Despite the extensive literary manuscripts and letters that survive, Keats destroyed or neglected his papers, much of which are extant because friends took the pains to preserve or transcribe them. It is well known that the letters he received from his fiancée Fanny Brawne are buried with him in Rome. Belle da Costa Greene famously burned her personal papers at the end of her life and is even more elusive in the archive than Keats. Yet these gaps have a presence; they leave traces of writing alluded to but no longer with us. As “scraps of words written in fire,” these archival lacunae haunt the story of Belle Greene and John Keats while at once contributing to their respective mythologies.

The scraps of paper on display in this exhibition trace an activity typically invisible to museum visitors, namely the work of librarians and archivists, as exemplified by the career of Belle da Costa Greene. The exhibition’s physical location in the museum is significant in that regard, as the Rotunda is positioned mere steps away from Belle da Costa Greene’s former office in the North Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library. It is there where she wrote her correspondence with bookdealers, planned the English literature exhibition at NYPL, met with Amy Lowell, and drafted the first research guide to the Morgan’s Keats manuscripts.

Re-positioning Greene in multiple spaces of the library, and in multiple stories about the library, will continue to be a major emphasis as we move toward 2024, when the Morgan will mount a major exhibition on Belle da Costa Greene to celebrate its centenary as a public institution.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to colleagues at the Morgan Library & Museum who have contributed their expertise to make this physical and digital exhibition possible, especially Christine Nelson, Sal Robinson, Marilyn Palmeri, Graham Haber, Janny Chiu, Reba Fishman Snyder, Frank Trujillo, Ian Umlauf, Emily Quint-Hoover, Joelle Seligson, Daria Rose Foner, Sheelagh Bevan, John Alexander, Keith Johnson, and Sholto Ainslie.

Special thanks to Ilaria Della Monica and Michael Rocke of Villa I Tatti for granting permission to use images from the Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers.

I am also grateful to the scholars and curators who have written on John Keats and Belle da Costa Greene, including Heidi Ardizzone, Jean Strouse, Aileen Ward, Andrew Motion, Stanley Plumly, Grant F. Scott, Susan J. Wolfson, Margaret Homans, John Barnard, Stephen Hebron, Robert Gittings, Jack Stillinger, James L. Weil, Flaminia Gennari-Santori, Hyder Edward Rollins, Sidney Colvin, and Amy Lowell.

Lastly, I would like to extend my deep admiration for the work and legacy of Belle da Costa Greene, whose expertise and dedication made the Morgan’s Keats collection, indeed the Morgan as a whole, what it is today.

–Philip S. Palmer, Robert H. Taylor Curator and Department Head, Literary and Historical Manuscripts

Photography of Morgan Library & Museum objects by Graham Haber and Janny Chiu

Photographs of Belle Greene letters to Bernard Berenson, Biblioteca Berenson, I Tatti - The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies, courtesy of the President and Fellows of Harvard College