Morganmobile: In Disguise

In life, things are sometimes not as they appear. And they’re almost never so in art, a realm of endeavor that relies on suspending disbelief. Eye-fooling illusions, comedies of error, the plots and subterfuges of gods and tricksters: Take a good close look, and then take another.

Morganmobile: In Disguise

Guercino here depicts an episode from Giovanni Battista Guarini's Il Pastor Fido. The nymph Dorinda was in love with Silvio, who cared only for hunting. She disguised herself as a wolf in order to watch him. Silvio, however, mistook Dorinda for his prey and shot her. The shepherd Linco came to her aid, and Silvio, having fallen in love with Dorinda, offered her the bow so that she could take revenge on him. Only slightly wounded, Dorinda refused, and, with their love now realized, the couple married.

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, called Il Guercino (1591–1666), Silvio Discovering the Wounded Dorinda, Supported by Linco, ca. 1646–47. Pen and brown ink and wash. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan in 1909, inv. I, 101g.

Morganmobile: In Disguise

Decoys and body doubles, common in the pages of modern thrillers, go back thousands of years. At the center of these two scenes from the Crusader Bible, the young David—then serving as court musician to King Saul—escapes the king’s soldiers through a window and is reunited with the prophet Samuel. On the left, we see the mastermind of David’s escape: Michal, David's wife and the daughter of Saul. She shows the soldiers what appears to be her slumbering husband, but is actually a statue she has installed in his bed.

Crusader Bible, with added texts in Latin, Persian, and Judeo-Persian, France, Paris, ca. 1250., MS M.638, fol. 31r (det).; Purchased by J. P. Morgan in 1916.

Morganmobile: In Disguise

It is difficult to tell where the mask worn by this figure ends and his face begins—or is it a mask at all? Inspired by travels abroad and by ancient mythology, Robert Lostutter creates drawings and watercolors that merge humans, birds, and plants into fantastical hybrids. The otherworldly subject of this drawing is made all the more strange by the refined and precise style in which it is rendered.

Robert Lostutter (b. 1939), Night Garden, 2015. Graphite, 26 11/16 x 37 in. (67.7 x 94 cm). Gift of Mark and Judy Bednar; 2016.54.

Copyright © 2015 Robert Lostutter. Courtesy the Artist and Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago.

Morganmobile: In Disguise

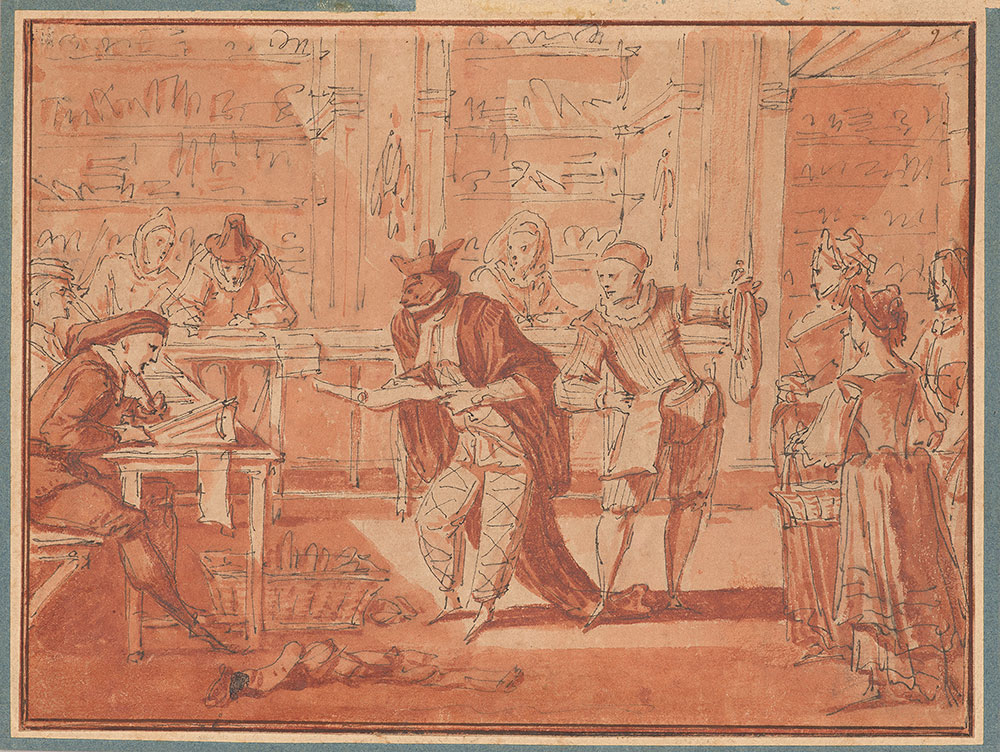

In a series of over forty drawings derived from contemporary satires, Claude Gillot chronicled the audacious antics of Harlequin, the resourceful protagonist of slapstick comedies performed at open-air theaters. This scene from a romantic farce depicts Harlequin disguised in the robes of a police commissioner, bringing a document to be signed. The notary, played by Scaramouche, believes it to be a complaint, but Harlequin, and the audience, know it is a marriage contract.

Claude Gillot (1673–1722), Harlequin, False Commissioner, at the Notary. Pen and black ink with red watercolor over traces of black chalk. Purchased on the Rousuck Fund and the Ryskamp Fund, inv. 2017.333.

Morganmobile: In Disguise

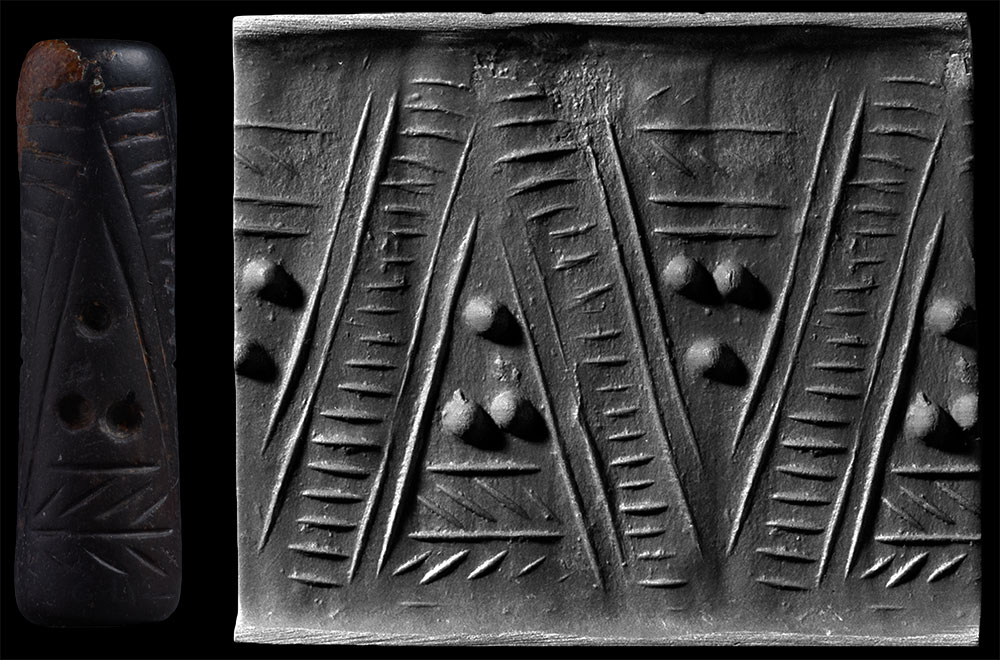

The meaning of the design carved on this cylinder seal remains unknown. It comes from a group of seals carved with geometric and—to today’s eye—abstract designs, rather than the figural or narrative scenes more typical of this early period. All of these enigmatic seals feature variations on the elements seen here. The motifs surely conveyed meaning; carving was a labor-intensive art and the stone itself was a valuable raw material, imported to the Mesopotamian flood plain. If, as is speculated, the designs are derived from weaving and mat plaiting, then each pattern might identify an individual potter or weaver—or indeed a clan, like the tartan patterns of Scotland. Whatever the meaning, the code has yet to be cracked.

Ancient cylinder seal with modern impression, Zig-Zag ‘Ladder’ Patterns, Mesopotamia, Late Uruk/Jamdat Nasr period (3500–2900 b.c.). Black serpentine, overall 1 7/8 x 9/16 in. (4.8 x 1.4 cm.), Morgan Seal 35. Acquired by Pierpont Morgan sometime between 1885 and 1908.

Morganmobile: In Disguise

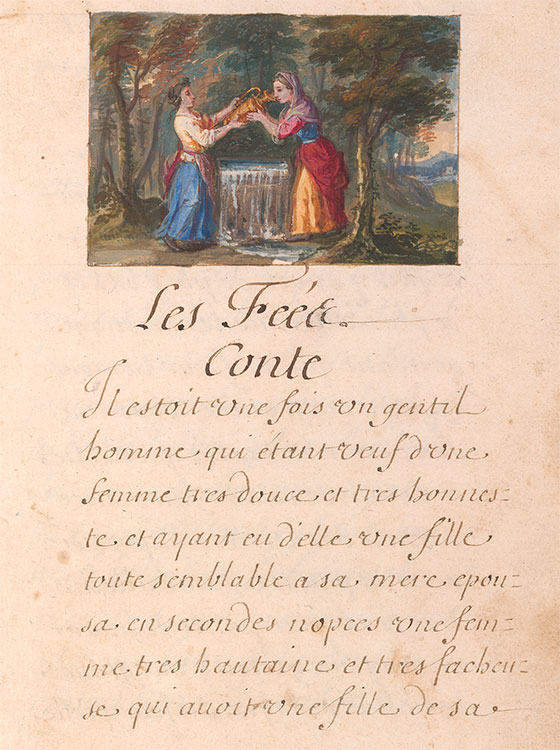

Imagine if simple acts of kindness were rewarded with boundless riches! In the French fairy tale “Les fées” (“The Fairies”), a young woman provides refreshment to an older woman in need. The latter proves to be a fairy in disguise, who announces “that with every word you speak, a flower or a precious stone shall fall from your mouth.” Like Cinderella, another heroine with a patron fairy, the young woman (now spewing jewels with every utterance) soon finds herself a royal husband. This, the earliest known written text of “Les fées,” is part of a splendid presentation manuscript of the tales of Mother Goose created as a gift for Élisabeth Charlotte d’Orléans, niece of France’s King Louis XIV.

Charles Perrault (1628–1703), Contes de ma mère l'Oye, scribal manuscript with gouache headpieces, 1695. MA 1505. Purchased as the gift of the Fellows, 1953.

Morganmobile: In Disguise

Art photography that imitates the aesthetics of painting—so-called “Pictorial” photography—is nearly as old as the medium itself. Pictorialists of the nineteenth century staged didactic allegories and sentimental genre scenes; the title of this later effort cites a modernist school, Cubism. A. Aubrey Bodine, whose work appeared both in art photography “salons” and in a weekly feature in the Baltimore Sun, did not stoop to darkroom manipulation in creating this head-turning abstraction. Stare at his straight photograph the right way, and the zigzagging subjects will reveal themselves. Common sights on the streets of Baltimore, they were quarried in nearby Cockeysville, Maryland.

A. Aubrey Bodine (1906–1970), Cubist Design, 1945. Gelatin silver print. Purchased on the Photography Acquisition Fund, 2017.388.

Morganmobile: In Disguise

The Hypnerotomachia Poliphili is the most majestic, and most cryptic, illustrated book of the European Renaissance. Its labrynthine text, written in a hybrid language of Latin and Italian, leads the reader through an erotic dreamscape of architectural ruins, gardens, and classical imagery. Speculation persists as to its interpretation and authorship. Read as an acrostic, the opening ornamental letters of the book’s chapters spell out: “Poliam Frater Franciscvs Colvmna Peramavit” (Brother Francesco Colonna loved Polia immensely). The A on this page is the A in “Francesco”—a Dominican friar long thought to have thus revealed himself as creator of the Hypnerotomachia.

Francesco Colonna (1433–1527), Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (The Strife of Love in a Dream by the Lover of Polia), Venice: Aldus Manutius, 1499. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan with the library of Theodore Irwin, 1900. PML 373.

Morganmobile: In Disguise

Preparing a monk’s body for burial, these nuns make a shocking discovery: Brother Marinos was a woman. Marina was raised a devout Christian by her widowed father, Eugenius, who entered a monastery when she reached marriageable age. She refused to wed; instead, she disguised herself as a man and entered religious life with him. Later accused of impregnating an innkeeper’s daughter, Marina was banished and obliged to raise the child alone. Ten years later she was readmitted to the monastery, where she was assigned duties of especially hard labor. Dead at age forty, her secret revealed, Marina worked miracles at her funeral and, becoming a saint, was venerated for her silent obedience to authority.

The Discovery of St. Marina’s Disguise, from Jacobus de Voragine, Golden Legend, in French, Belgium, Bruges, 1445–65. MS M.675, fol. 136 (det.). Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1911.

Morganmobile: In Disguise

Facing a cast of players that look ready for their supper, a local studio’s photographer attempts to frame the participants in one town’s patriotic holiday pageant. The minute-long panning exposure of his banquet camera records some two hundred characters derived from history, civic heraldry, literature, and legend. Pilgrims, Conquistadors, and Betsy Ross rub elbows with Liberty, Johnny Appleseed, and a troupe of bobbed-haired ukulelists. Inclusive though the script of the event appears to have been, one feature of costuming signals profound exclusion. The disenfranchised of history—Black and Mexican laborers and native peoples of the continent—are represented by players in blackface and brownface. The clear, if unconsidered, message to today from Labor Day, 1925: the nation’s saga, however rich and varied its interpretation, was still understood as a story fit to be enacted—and embodied—by white Americans only.

C. Hart Studio, Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio, 7th Annual Pageant, Held at Hinckley, Ohio, Labor Day, September 7, 1925. Gelatin silver print. Purchased on the Photography Acquisition Fund, 2018.62.

Morganmobile: In Disguise

Teeming with life, this intricate letter B serves as the frontispiece for a deluxe book of the Psalms, possibly created for King Edward I of England (1239–1307). A tree sprouts out of the recumbent figure of Jesse at lower center and grows straight upward, bearing his descendants: King David, the Virgin Mary, and, at the top, Christ. On the right side of the B, amid prophets, evangelists, and Creation scenes, four camouflage leaf men climb cautiously through the entangled vine scrolls. These curious human-vegetal hybrids help animate the letter and provide a moment of delight for those who find them.

Beatus Initial with Tree of Jesse from The Windmill Psalter, England, possibly London, ca. 1280–1300. MS M.102, fol. 1v. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1902.

Morganmobile: In Disguise

Nicolas Trigault was a Jesuit missionary who spent much of his life working in China. On the controversial advice of Matteo Ricci, one of the founders of the country’s Jesuit mission, Trigault traded his plain black Jesuit garb for the robes of a Chinese literatus. Ricci believed that by appropriating the dress of the country’s intellectual elites, the Jesuits would gain more direct access to powerful members of Chinese society. Trigault appears to have brought his Chinese clothes with him during a return visit to Europe, where he was drawn by seventeen-year-old Anthony van Dyck.

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641), The Jesuit Nicolas Trigault in Chinese Costume, 1617. Black and green chalk on laid paper, traces of framing line in black chalk. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1909, inv. III, 179.

Morganmobile: In Disguise

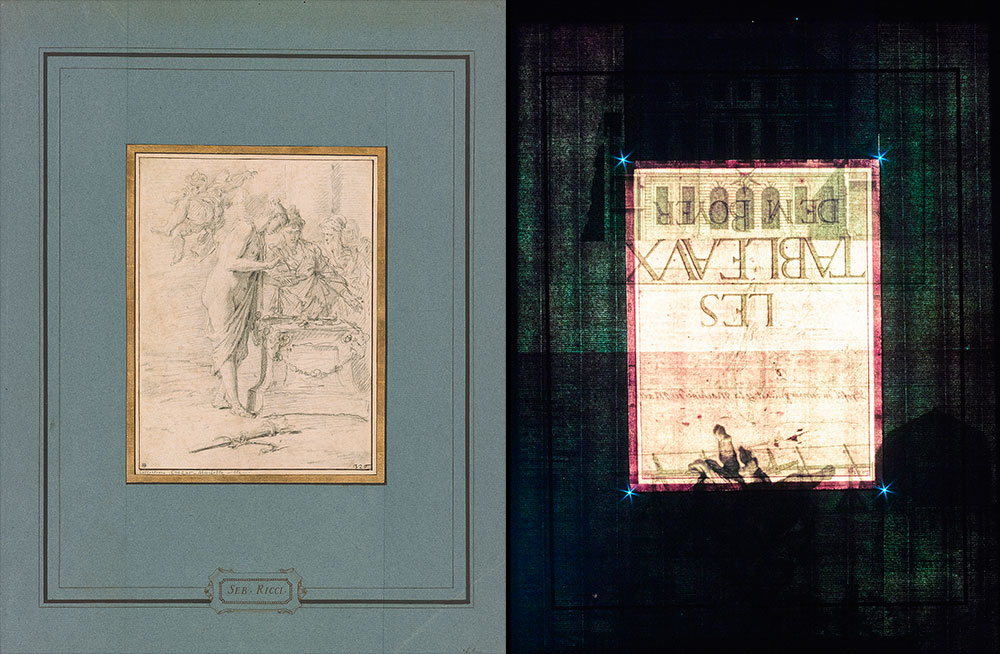

To display the drawings in his collection, Pierre-Jean Mariette (1694–1774) designed elegant blue mounts that would influence generations of European collectors. When viewed with light passing through them, many of Mariette’s mounts turn out to contain cast-off printed matter from his family’s publishing business. As seen in the transmitted-light image at right, this drawing by Sebastiano Ricci and its mount hide two sheets that are adhered face to face: an architectural print and a title page for Les Tableaux de M. Boyer, ca. 1744. The Ricci drawing, surrounding blue paper, and gold strips were adhered to the front of the mount, completely concealing the prints.

Sebastiano Ricci (1659–1734), Venus and Cupid with other Figures before an Altar, 17th century. Black chalk on paper. 8 11/16 x 6 1/2 inches (220 x 165 mm). Purchase. 1950.5.

Morganmobile: In Disguise

Several weeks after, and some miles away from, the first battle of the English Civil War, the baronet and antiquary Edward Dering was arrested while traveling under an assumed name. After his release he petitioned for the return of property confiscated from him while in custody. His protestations of innocence are not entirely supported by his list of the items he was carrying when arrested, which ends: “And a false beard to disguise my selfe withall, but not used.”

Edward Dering (1598–1644), Letter to George Brydges, Shrewsbury, 1642 December 15. MA 3097 (p. 2). Purchased on the Acquisitions Fund, 1973.