Morganmobile: Telling Fragments

The stuff of history survives selectively. The past we know is constructed out of that which remains. Some artifacts are all too clearly fragmentary—but sometimes, too, fragmentation tells a beautiful story never heard before.

Morganmobile: Telling Fragments

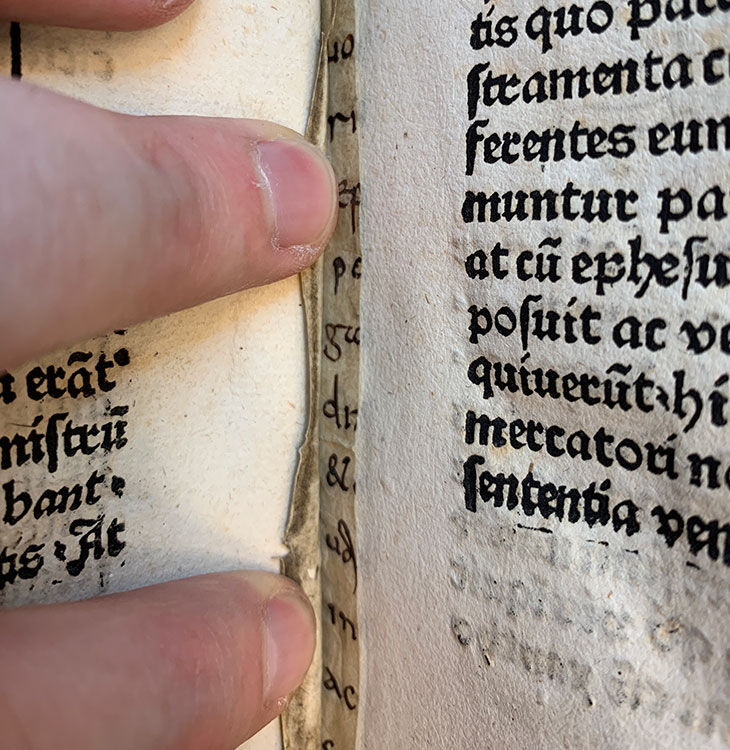

Hidden in the gutter (the fold between facing pages) of this printed Aesop are fragments of a much older hand-written book. The little strips are too narrow to allow the text to be identified, but the style of the handwriting suggests the manuscript is from southern Germany in the ninth century. By the 1480s, the 600-year-old manuscript was considered useless and cut up to reinforce the binding of this new book.

Aesop, Vita et Fabulae [Augsburg: Anton Sorg, not before 1483]. Purchased with the Bennett collection, 1902. PML 153.

Morganmobile: Telling Fragments

This corroded fragment from an iron buckle, lacking its loop, testifies to an era of robust cultural exchange in eighth-century Spain. Objects of similar style, found concentrated in the region of ancient Hispalis (Seville), may have been produced in local workshops in Baetica, corresponding roughly to modern Andalusia. The inlaid decoration reveals familiarity with ornamental motifs in Egyptian, Syrian, and central-Asian textiles. The imitation of Sasanian (Persian Empire) motifs such as the animals with neck bands and floating scarves may reflect intensifying contact with the East and the subsequent settlement that resulted in the establishment of the Umayyad Caliphate in Spain.

Lyre-shaped buckle plate, Hispano-Visigothic or early Umayyad period, eighth century. Iron with inlays of brass or copper alloy. Thaw Collection, 2012.2.69.

Morganmobile: Telling Fragments

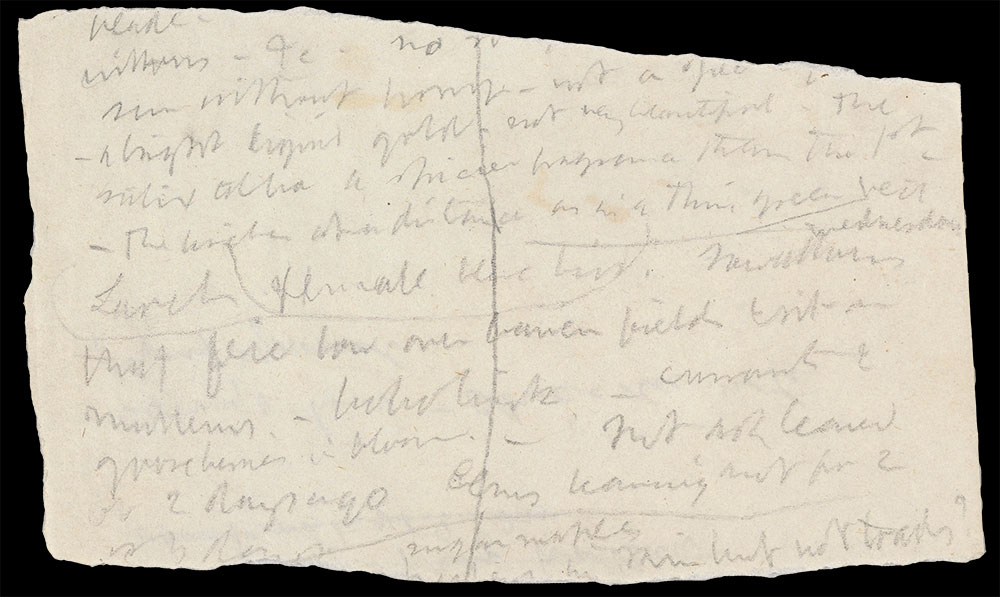

While taking long daily walks around Concord, Massachusetts, Henry D. Thoreau carried scraps of paper in his pocket. He would use a pencil to jot down some of the things he saw. In May 1852, he observed “birches at a distance as in a thin green veil. . . . Swallows that flie low over barren fields & sit on mulleins. . . . currants & gooseberries in bloom . . . .” He would let his thoughts and observations mature, then sit down at his desk later to write in his journal and turn fragmentary field notes into prose. The last few words on this scrap read “rain but not toads?” In his journal, Thoreau wrote “Hear the peepers in the rain to-night but not the dream toads.”

Henry D. Thoreau, field notes for May 1852, inserted in his journal notebook for 31 August 1852–7 January 1853. MA 1302.19. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909.

Morganmobile: Telling Fragments

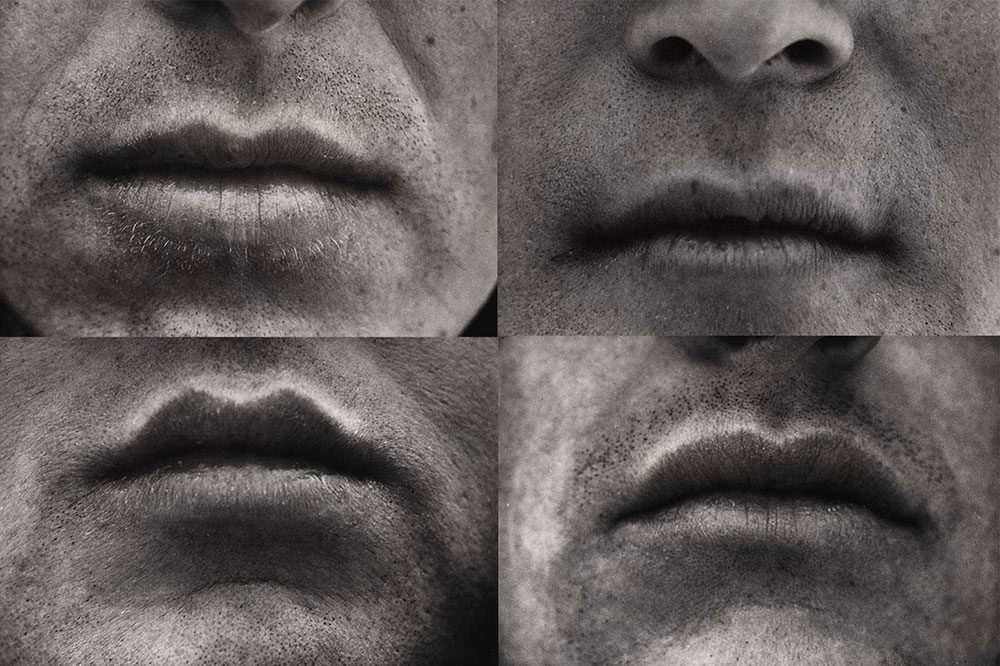

To photographers in the 1960s whose beat was pop music, the fame of the Beatles presented both an opportunity and a challenge. Nearly any image of the band stood a chance of getting published, but winning the battle for substantial page space called for ingenuity. When granted brief access to the four musicians, Jean-Pierre Ducatez made four puzzle-portraits that rely on a fan/viewer’s avid attunement to the features—specifically the lips—of her idols. These photographs ran on a full page in the September 1965 issue of 16 magazine under the heading “Kiss Your Favorite Beatle!”

Jean-Pierre Ducatez (b. 1941), Beatle Lips: George Harrison, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr, 1965. Gelatin silver prints. Purchased as the gift of Allen Adler, 2015.51:1–4. © Jean- Pierre Ducatez.

Morganmobile: Telling Fragments

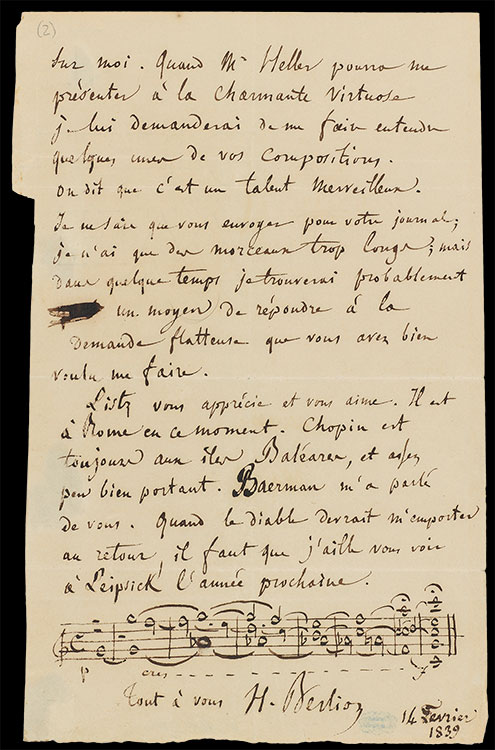

On Valentine’s Day, 1839, Hector Berlioz writes from Paris to his fellow composer—and fellow music critic—Robert Schumann. He mentions friends, including Franz Liszt and Frédéric Chopin, and notes that the renowned pianist Clara Wieck, whom Schumann will soon marry, has arrived in Paris. Even while urging his German colleague to join her there, Berlioz remarks of his city: “There are few honest young men worthy of the name of artist, and many gnomes and a lot of morons and above all scoundrels (you see that I observe the law of crescendo).” At the end of the letter, perhaps to underline his crescendo of epithets, Berlioz renders an unidentified musical fragment consisting of a swelling series of harmonies.

Hector Berlioz (1803–1869), letter to composer Robert Schumann, 14 February 1839. Mary Flagler Cary Collection, MFC B515.S392.

Morganmobile: Telling Fragments

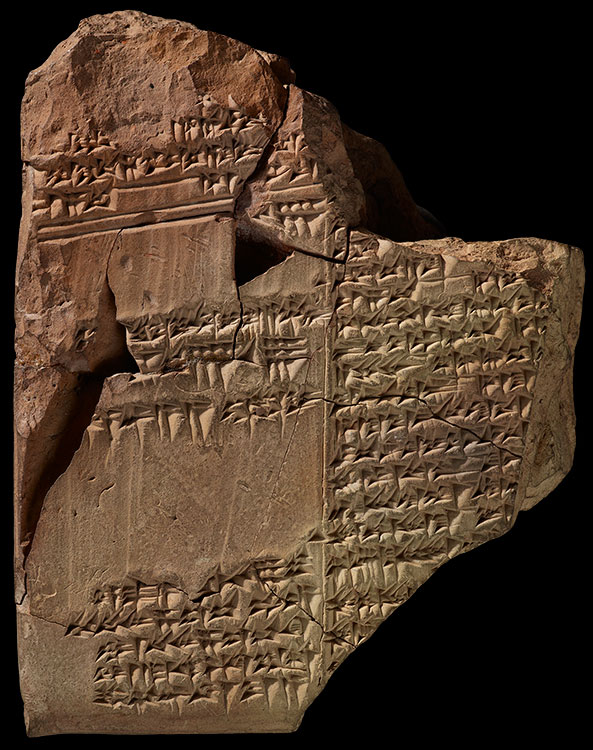

This precious fragment includes the earliest known Akkadian version of the familiar Noah motif. The story, originally comprising over 1200 lines on three tablets, begins with the creation of man, when “great indeed was the drudgery of the God.” The gods tire of humanity and, when they decide to destroy it, the god Enki (Ea) tells Atrahasis to build an ark before the impending flood. The Morgan's fragment, from the second tablet or chapter, includes an extraordinary colophon with information about the object: the work’s title (“When gods were men”), an attribution (“the junior scribe Ku-Aya”), and the place and date of its making (the city of Sippar during the eleventh year of the reign of Ammi-saduqa, King of Babylon—great, great grandson of King Hammurabi).

Tablet inscribed with a fragment of the Babylonian flood story Epic of Atrahasis in Akkadian, Mesopotamia, First Dynasty of Babylon, reign of King Ammi-saduqa (ca. 1646–1626 B. C.). Clay, 114 x 90 mm. Acquired by Pierpont Morgan before 1900. MLC 1889.

Morganmobile: Telling Fragments

This woodcut print depicts Saint Francis of Paola as he traveled through Provence, curing people of the plague on his way to visit King Louis XI around 1483. It must have been printed in large numbers; the colors were applied with stencils in order to speed up production. This print was found with several others inside the front cover of a French law manuscript, which explains the damage around its edges. The prints were probably unsold stock, recycled as scrap paper for the book’s cover—a true paperback.

Saint Francis of Paola Arriving and Preaching in Toulouse, Toulouse, 1480–90. Gift of Mr. H.P. Kraus in honor of Curt Bühler's 80th birthday, 1985. PML 78407.1.

Morganmobile: Telling Fragments

This battered page containing a dreamy love lyric in Percy Shelley’s hand survived the shipwreck that killed its creator. It was retrieved from the hull of Don Juan, Shelley’s new sailboat, after the boat foundered off the coast of Viareggio on July 8, 1822. From amid gaps and tears in the paper comes an evocation of fading song: “The wandering airs they faint / On the dark, the silent stream.”

Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822), fair copy of “The Indian Serenade,” 1821 or 1822. MA 814. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1907.

Morganmobile: Telling Fragments

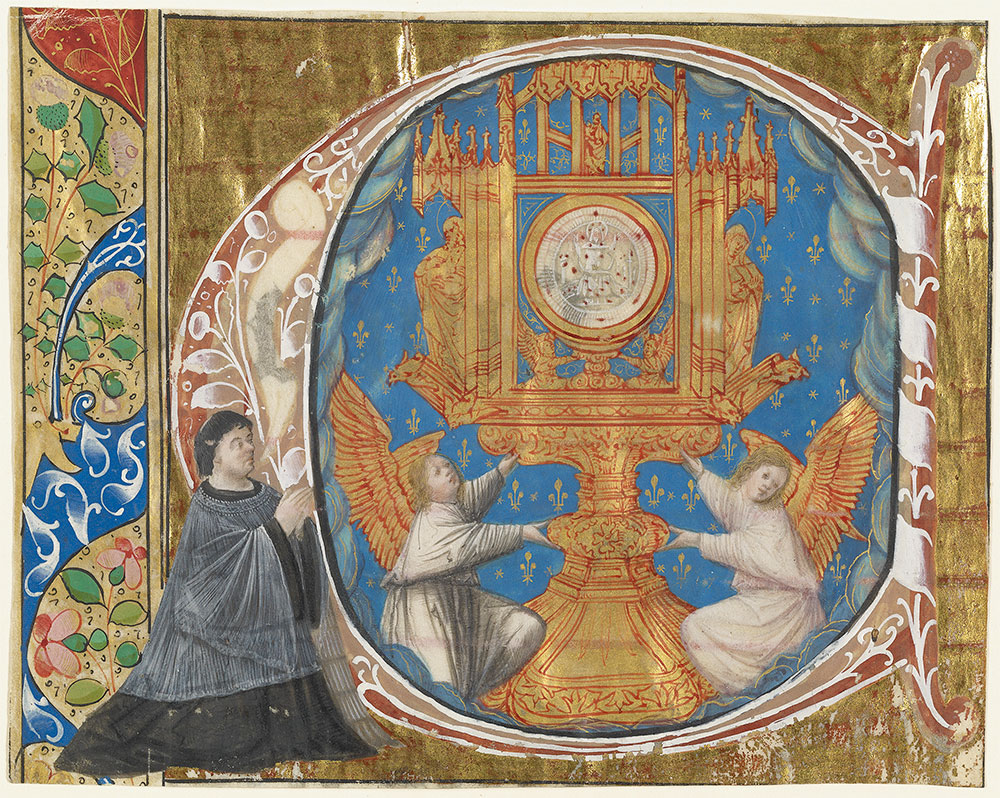

This large “C” encloses a gold monstrance, the vessel for displaying a communion wafer. The distinctive image embossed on the wafer allows this fragment of illumination to be traced to a large multi-volume Gradual (the choir book containing the words and music for high Mass) commissioned in the 1520s by the canons of the Sainte-Chapelle in Dijon, France. The Sacred Bleeding Host of Dijon, known from over a dozen miniatures and prints, bore an image of Christ as Judge enthroned among the Instruments of his Passion. In 1433 Pope Eugenius IV gave the miraculously bleeding Host to Duke Philip the Good of Burgundy. Philip installed it in his ducal church in Dijon, which was renamed the “Sainte-Chapelle” because it contained a relic from Christ himself: his blood. Host, monstrance, and the Sainte-Chapelle itself were subsequently destroyed in the French Revolution. The Morgan fragment is one of only three that survive from this grand and elaborately illustrated Gradual.

Sacred Bleeding Host of Dijon, from a Gradual commissioned by the canons of Dijon’s Sainte-Chapelle and illuminated by the Master of the Bruyères Hours [(Oudot Matuchet?]), France, Dijon, 1520s. MS M.1144. Purchased on the Edwin H. Herzog Fund and the Fellows Endowment Fund, 2005.

Morganmobile: Telling Fragments

The support for this collage is an irregular piece of fabric edged in ink, as fragmentary as the components laid on top of it. A Holocaust survivor who settled in the Bronx, Hannelore Baron adopted the mediums of assemblage and collage. Her materials were hand-dyed papers and fabric scraps, embellished with monoprints made from copperplates, such as the figure with outstretched arms near the center of this composition. Baron’s collages suggest a world just barely held together. Deeply moved by the social upheavals of the 1960s and ‘70s, she described her art as a form of personal protest akin to “the way other people march on Washington, or set themselves on fire.”

Hannelore Baron (1926–1987), Untitled, 1977. Collage of cut colored and printed papers and cloth with pen and ink on cloth, 7 5/8 x 7 7/8 in. (19.4 x 20 cm). Gift of Elise Boisanté and Mark Baron. 2008.12. ©Estate of Hannelore Baron; courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY.

Morganmobile: Telling Fragments

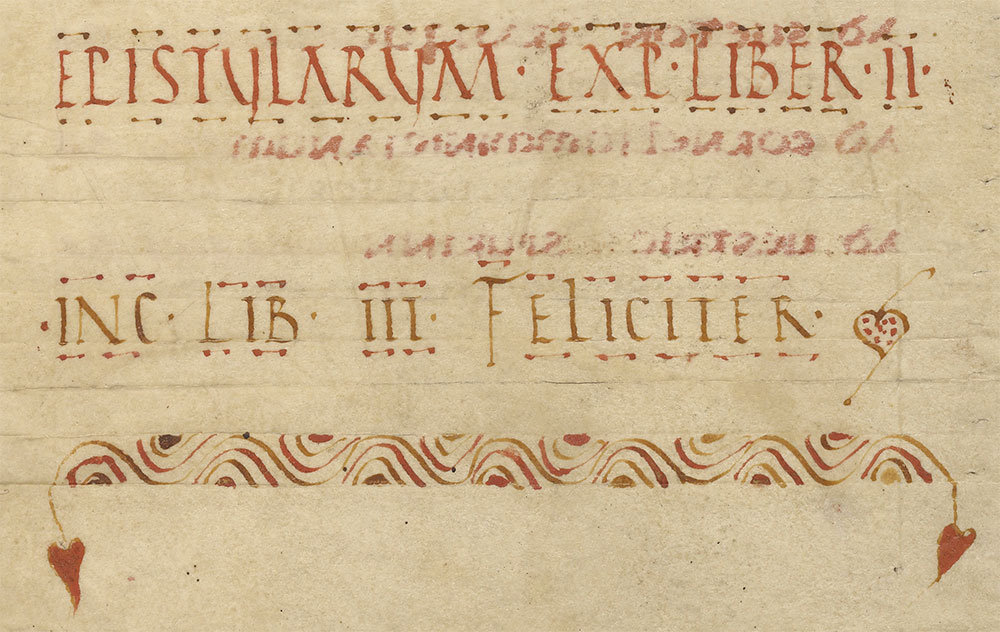

Six leaves at the Morgan are all that remain of the earliest known copy of the letters of Pliny the Younger, a Roman lawyer, magistrate, and author. The Letters provide fascinating insights into daily life in first-century Rome—including, most famously, Pliny’s firsthand account of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 and descriptions of his dealings with the burgeoning Christian community. Although written in Italy, the manuscript survived for centuries in France, eventually forming part of the celebrated library at the Abbey of Saint Victor, near Paris. It was ‘discovered’ there by Renaissance scholars from Italy, who recognized its value as the oldest and most complete copy of Pliny’s text. They sent it to Venice, where it provided the basis for the first printed edition of the Letters in 1508. Probably as a result of this period of intense study and use, the ancient manuscript was dismembered and lost, but for the fragment Pierpont Morgan acquired in 1910.

Fragments from Books II and III of the Letters of Pliny the Younger (61–ca. 113 CE). Written by an unknown scribe in Italy, late fifth century. MS M.462, fol. 1r (detail). Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan in 1910.

Morganmobile: Telling Fragments

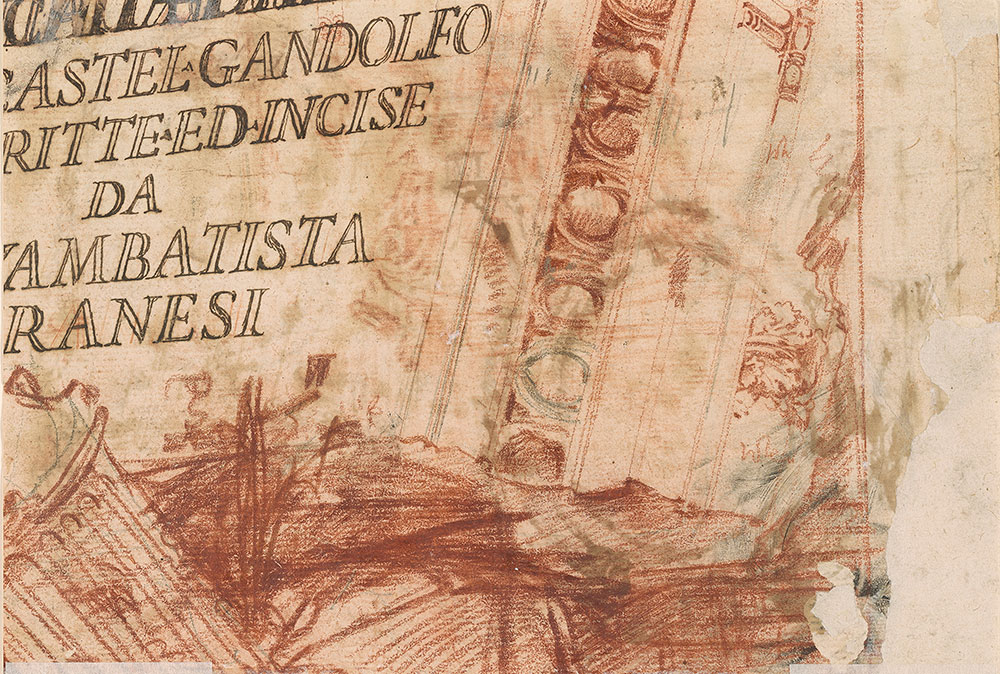

Though hundreds of drawings survive from Piranesi’s workshop, few are complete preparatory studies for his most famous prints. However, many drawings turn out to have, on their versos or back sides, fragments of larger preparatory drawings. This suggests that once Piranesi had transferred an idea to the copper plate, he would cut up the preparatory study and reuse the paper for new sketches. Here, part of a study for a title page survives on the verso of a sheet used for studies of an ornamental frame.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–1778), fragment of a title-page design for the Antichità d'Albano e di Castel Gandolfo, ca. 1764. Red and black chalk. Bequest of Junius S. Morgan and gift of Henry S. Morgan, inv. 1966.11:71 verso.

Morganmobile: Telling Fragments

This early printed devotional book exists only in two fragments, one at the Morgan, one at the Bodleian Library in Oxford. Now in a modern binding, the Morgan fragment consists of sixty-four leaves, maybe two-thirds of the book’s original contents. No leaves survive from the beginning or the end, where the volume suffered most from wear and tear. Even in its tattered state, it tells about an important episode in the introduction of printing to England. Before William Caxton set up his press in Westminster, around 1476, he printed this and several other books in Bruges, where he commissioned types from a gifted scribe and expert pressman, Colard Mansion. This book is now thought to have been printed in Bruges in 1475 or 1476 by Caxton and Mansion, no doubt with the intention of exporting copies to England. It is the earliest known example of an English book printed on vellum with hand illumination, which can be seen here in the borders and the decorated initial.

Catholic Church, Book of hours (Sarum) [Bruges: Colard Mansion?, for William Caxton, about 1475–1476]. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1908; PML 18386.

Morganmobile: Telling Fragments

A photograph is an abstraction, in that word’s original sense. Having framed a portion of reality in the viewfinder, the photographer abstracts it—removes it—from its real-world context. Katrien de Blauwer’s photo collages redouble the medium’s unreality effect. These works exemplify three of the simple yet potent effects she derives from pictures cut out of old magazines. At left, a single image is split, then rearranged, producing a cinema-like stutter. In the center, two variants on a subject (tops of heads) become one another’s echo. On the right, two unimportant-looking details are married by Blauwer into an uncanny new whole.

Katrien de Blauwer (b. 1969), left to right: Single Cuts (99), 2014; Rendez-Vous (50), 2015; Rendez-Vous (55), 2013. Collages. Purchased on the Photography Collectors Committee Fund. 2017.287–289. © Katrien de Blauwer

Morganmobile: Telling Fragments

This sampler from Jen Bervin’s artist’s edition, The Dickinson Composites, relates to her large-scale quilt project of the same name. She described the work as making “mends of omission.” The red specks embroidered on muslin-backed cotton batting are a composite of the idiosyncratic marks found in one of Emily Dickinson’s manuscript fascicles. Dickinson used crosses to indicate alternate word choices, which she provided in footnotes and left unresolved. Early editors of her publications chose to efface them. Bervin chose instead to efface the language. Her markings point both to the absence of poetry as well as the historical suppression of the poet’s unique textual practice.

Jen Bervin (b. 1972), The Dickinson Composites, New York: Granary Books, 2010. Purchased on the Henry S. Morgan Fund, 2016. PML 196475.

Photography courtesy of Jen Bervin.