Morganmobile: Inside/Outside

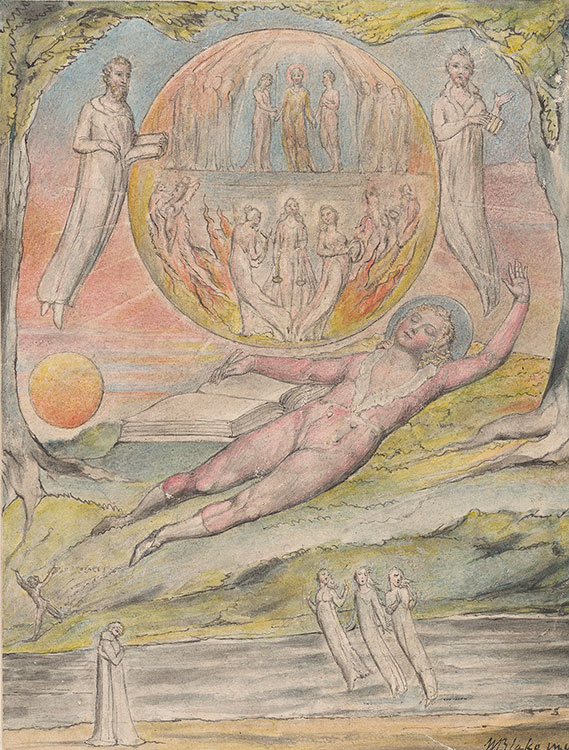

This pastel-hued watercolor is the last of William Blake’s six illustrations for John Milton’s 1645 poem L’Allegro, or Happiness. As the sun sets, a young poet falls asleep, pen in hand, along the banks of a stream. His body, though immersed in the landscape, transcends it as he leaves the waking world. Blake gives form to the unconscious poet’s visions as a “more bright sun”—the Sun of Imagination—filling the upper half of the sheet.

William Blake (1757–1827), The Youthful Poet’s Dream, 1816–20. Watercolor, over graphite, on paper. Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows with the special support of Mrs. Landon K. Thorne and Mr. Paul Mellon. 1949.4:6

Morganmobile: Inside/Outside

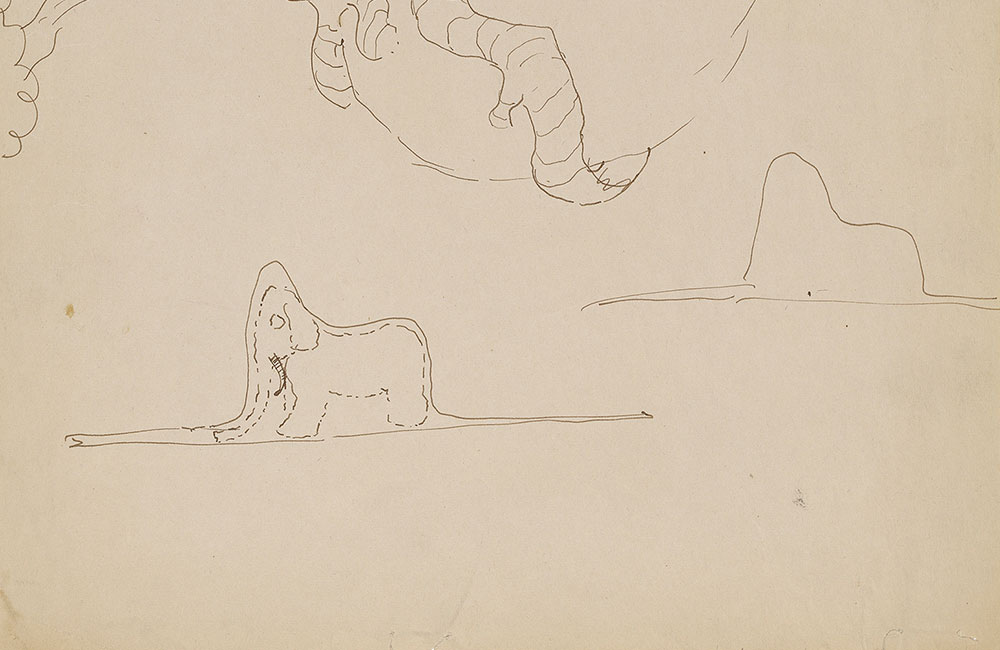

What do you see in the shape to the right? It is a sketch for the first of the unforgettable images that appear in the opening paragraphs of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s 1943 tale The Little Prince. Saint-Exupéry recalls learning, in youth, that grown-ups tended to see only the outside of things. His second sketch (below left) allows us to peer inside the first. “My drawing was not a picture of a hat,” he writes:

It was a picture of a boa constrictor digesting an elephant. But since the grown-ups were not able to understand it, I made another drawing: I drew the inside of the boa constrictor, so that the grown-ups could see it clearly. They always need to have things explained.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (1900–1944), Preliminary sketch for Le petit prince (The Little Prince), 1942. Purchased on the Elisabeth Ball Fund, 1968. MA 2592.18.

© Estate of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry.

Morganmobile: Inside/Outside

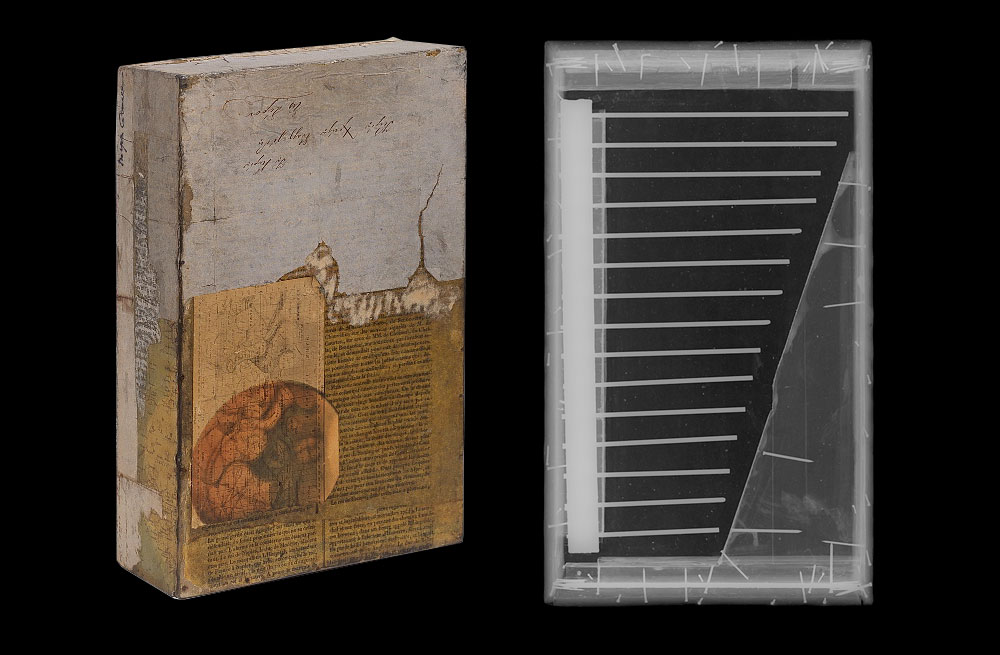

Joseph Cornell's best known works are glass-fronted shadow boxes that house, and reveal, fanciful assemblages, but he made a few boxes that are sealed on every side. Paper fragments of maps and texts in various languages decorate the exterior of this sealed box. What is inside? When it is rotated or given a quick shake, musical notes emanate from the interior. X-rays reveal that the box contains the metal tines of a toy piano—the light gray horizontal bars in the x-radiograph on the right. The object that strikes the bars to create the jangling sound eludes even x-ray vision; it manifests itself only when the box is handled.

Joseph Cornell (1903–1972), Untitled (Music Box 1952–1954. Wooden box (possibly containing toy piano tines and a ball) with collage of printed and handwritten papers on all sides. Gift of Ellen Cantrowitz. 2017.365. Digital X-radiograph taken at 30kV and 450mAs, by Shan Kuang, Samuel H. Kress Fellow in Painting Conservation at The Conservation Center, Institute of Fine Arts, NYU, 2018. ©️ Joseph Cornell/Artists Rights Society, New York.

Morganmobile: Inside/Outside

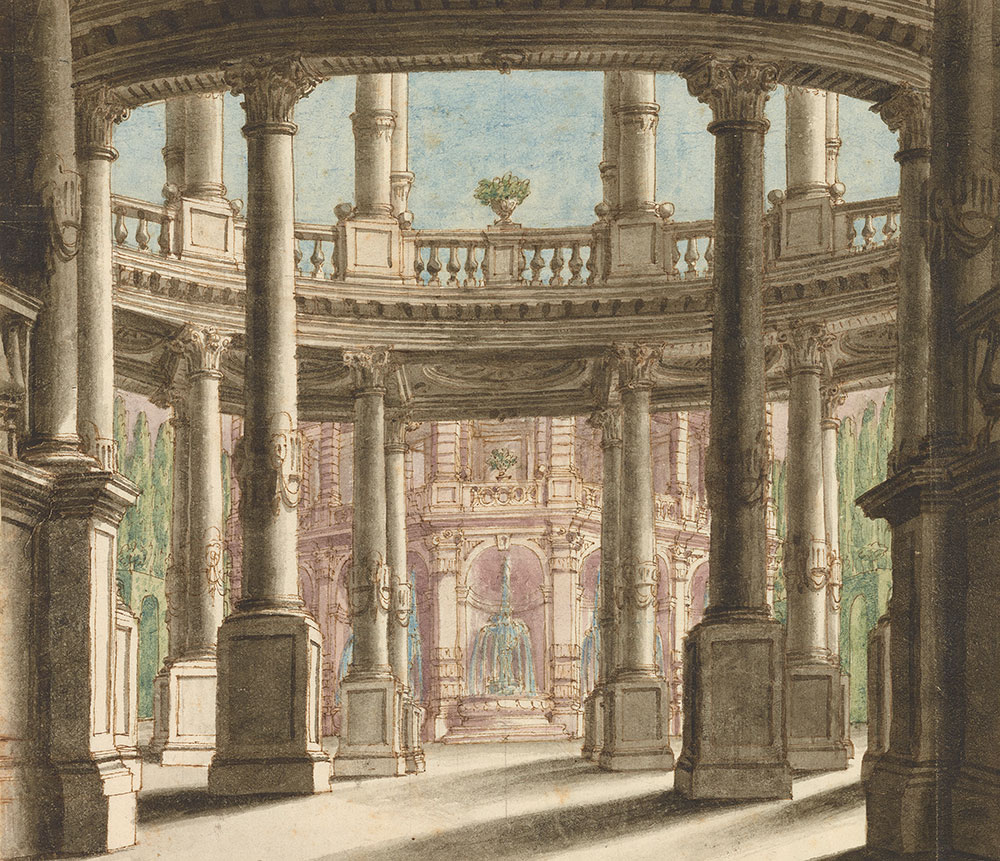

The Galli-Bibiena family revolutionized theater design in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In the theaters they built across Europe, their set designs made use of plunging perspectives and sometimes, as in this example, opened the interior architecture of the theater to long vistas onto distant gardens. In this design, perhaps for the Opera House at Beyreuth, an inscription identifies the scene as a “temple enclosure that leads to a lovely place.”

Carlo Galli Bibiena (1721–1787), An Open Circular Hall Looking onto a Garden. Pen and brown ink, gray wash, and watercolor, over graphite. Gift of Mrs. Donald M. Oenslager, 1982.75:104

Morganmobile: Inside/Outside

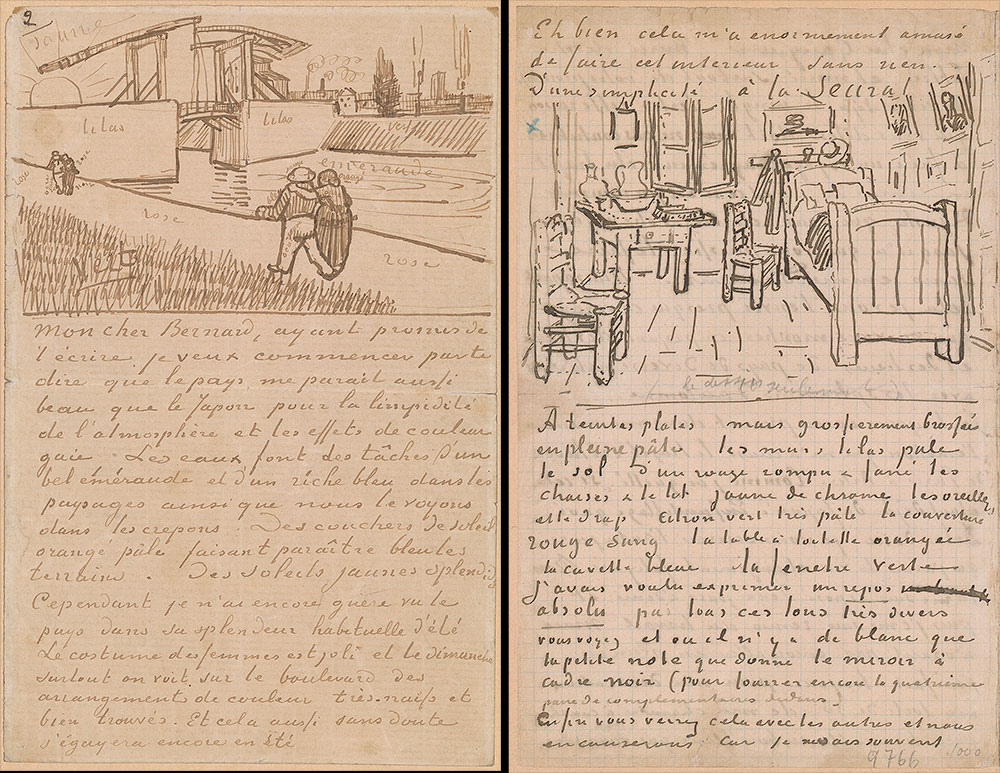

Upon leaving Paris for Provence early in 1888, Vincent Van Gogh wrote to his painter friend Émile Bernard: “Spleen is not in the air down here.” The move south inspired a richly creative period for the artist. Another letter to Bernard includes a drawing of the Langlois Bridge over the Rhône, whose “stretches of water make patches of a beautiful emerald.” In a later letter to Paul Gauguin, Van Gogh sketched his bedroom in the Yellow House in Arles. Avoiding the outdoors due to problems with his eyesight, he explains how he painted The Bedroom (Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam) “with a simplicity à la Seurat,” finding in its lilac, blood red, and pale lemon-green colors a feeling of “utter repose.”

Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), Autograph letter signed: Arles, to Émile Bernard, with sketch of the bridge at Arles, 1888 Mar. 18. MA 6441.2 (p. 1). Autograph letter: to Paul Gauguin, with sketch of “Bedroom at Arles,” 1888 Oct. 17. MA 6447 (p. 2). Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007.

Morganmobile: Inside/Outside

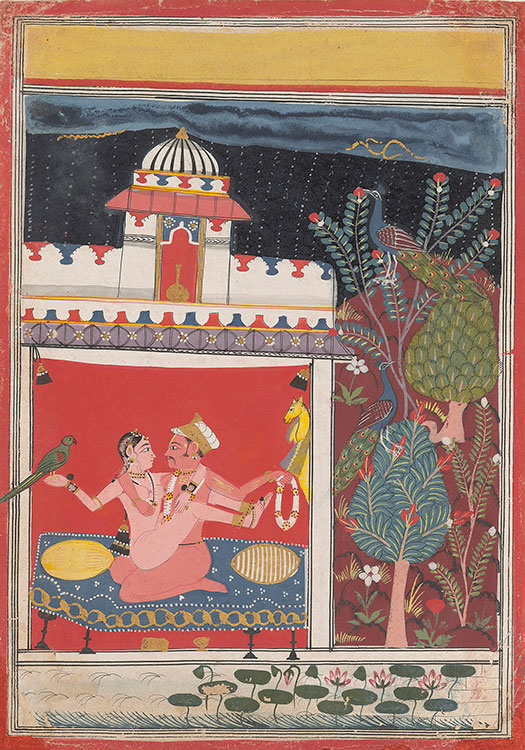

Protected from the raging storm outside, two lovers adorned with jewels consort in a pavilion, a common setting for romantic encounters in Indian miniatures. The white curtain at the entrance has been lifted, creating an unimpeded view into their private retreat, whose vibrant red interior seems to reflect the couple’s passion. As she straddles his body, he enfolds her in his embrace without dislodging the parakeet in her hand or the garland in his. The richness of the scene is enhanced by a lotus pond in the foreground and a lush garden inhabited by peacocks.

Erotic scene, north-central India, second half of the seventeenth century, MS M.1048.1. Gift of Paul F. Walter, 1983.

Morganmobile: Inside/Outside

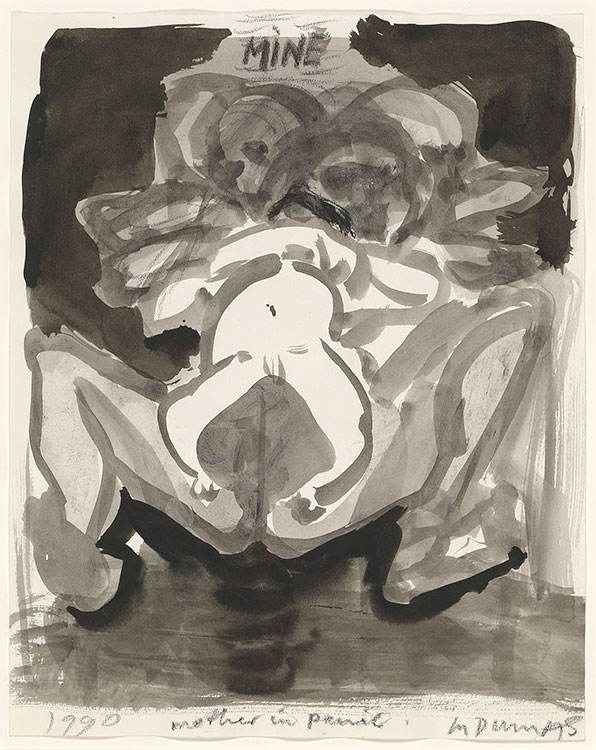

Titled Mother in Panic, this drawing appears to show a baby being birthed or, perhaps, pushed back inside its mother’s body. The word “Mine,” written at the top of the sheet, underscores themes of maternal possessiveness and ambivalence. Marlene Dumas made the drawing the year after her own daughter was born.

Marlene Dumas (South African, b. 1953), Mother in Panic, 1990. Watercolor on paper, 11 7/8 x 9 1/2 inches (30.16 x 24.13 cm). Gift of Howard Karshan. 2012.56.

© 2020 Marlene Dumas.

Morganmobile: Inside/Outside

The subject of this mammoth-plate photograph, a waterfall in upstate New York, fits within the genre of scenic landscapes—or, as marketing language of the period had it, “views.” Compositionally, the image owes more to the tradition of grand architectural interiors. Through his choices of viewpoint and lens length, William H. Rau caused the horizontal strata of Watkins Glen to form a starburst around the gauzy vertical stripe of Cavern Cascade. Rau’s 1895 series of photographs promotes points of interest along the routes of the Lehigh Valley Railroad—a company that J. Pierpont Morgan acquired two years later.

William H. Rau (1855–1920), Cavern Cascade, Watkins Glen, 1895. Albumen print from glass negative, 21 x 17 inches. Purchased as the gift of Ronald R. Kass. 2015.47:1.

Morganmobile: Inside/Outside

To depict events occurring indoors, medieval illuminators sometimes eliminated walls that would otherwise have closed viewers off from the action. Air, light, and people move freely among three spaces in this miniature. A female personification of Philosophy appears to Boethius in the bedroom at right, inspiring the author’s most famous work. In a connecting passageway Boethius hands the text to his future translator, Jean de Meun. And in the throne room, de Meun presents his translation of the Consolation to King Philip IV.

Boethius (ca. 477–524), The Consolation of Philosophy, in French and Latin, illuminated by the Coëtivy Master, France, Paris, ca. 1465. MS M.222, fol. 1 (det.). Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan in 1905.

Morganmobile: Inside/Outside

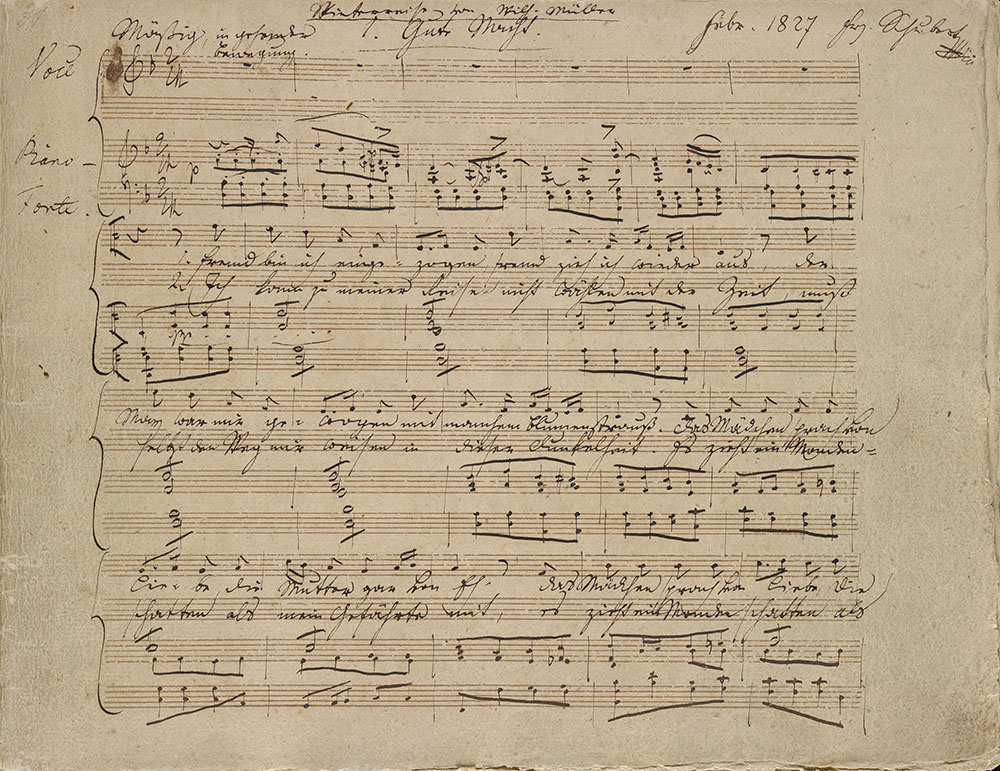

A sorrowful figure lingers outside a warm house on a snowy night, recalling the love of the girl who remains inside with her family. Soon he will begin his cold winter journey, told through the twenty-four songs of Franz Schubert's Winterreise cycle. To his lost love he sings: "You must not hear my footsteps... as I pass by I will write on the gate, ‘Goodnight,’ so that you will know I thought of you."

Franz Schubert (1797–1828), ”Gute Nacht" ("Good Night”), from Winterreise (Winter Journey). Autograph manuscript, 1827. Mary Flagler Cary Music Collection, 1968.

Morganmobile: Inside/Outside

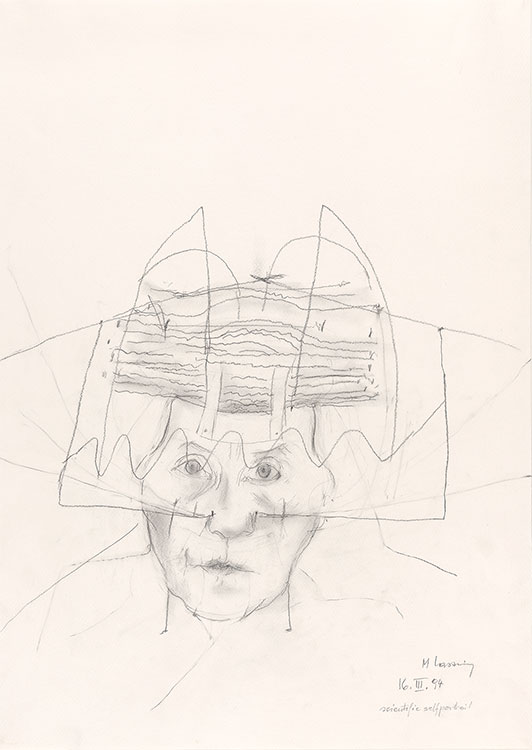

In her many self-portraits, Maria Lassnig offers a vision of her body from the inside, emphasizing the play of sensation—what she called “body awareness”—over visual representation. Here she humorously suggests the activity of her brain by surrounding her face with elements that evoke the scientific recording of neural activity.

Maria Lassnig (1919–2014), Scientific Self-Portrait, 1994, Graphite pencil on wove paper, 27 1/2 x 19 3/4 inches (70 x 50 cm). Gift of the Modern and Contemporary Collectors Committee. 2014.25.

© Maria Lassnig / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Morganmobile: Inside/Outside

In the surface of the white-banded agate cylinder at left, scarcely an inch high, is an incised image that becomes legible only when rolled out into clay. The scene, revealed at right, depicts a lion attacking a mouflon, a wild horned sheep. The lion’s ferocity, expressed through a series of arcs and curves, culminates in the curve of the head in profile, its mouth open to expose sharp teeth. The mouflon’s fear is apparent in the face it turns towards its attacker as it raises a foreleg in a vain effort to escape.

Lion Attacking Mouflon; Tree and Star. Mesopotamia, Middle Assyrian period (ca. thirteenth century B.C.). Banded agate, 1 1/8 × 1/2 inches (2.8 × 1.2 cm). Morgan Seal 602. Acquired by Pierpont Morgan between 1885 and 1908.

Morganmobile: Inside/Outside

A forest clearing stands ajar and leaf litter morphs into indoor-outdoor carpeting in this puzzle picture. The plates in Richard Gordon’s 1976 monograph, Meta Photographs, explore the unintended uncanniness of photo-based decor and advertising. Gordon saw that the photographic prop—an inescapable presence in postwar public space—had come to shape the optical experience of city-dwellers as pervasively as plate glass and gaslight had done for their ancestors a century before.

Richard Gordon (1945–2012), North Beach, San Francisco, 1976. Gelatin silver print. Purchase, Photography Acquisition Fund. 2017.372.

© Estate of Richard Gordon