Morganmobile: Rough Drafts

Created in Provence around 1440–50, the manuscript known as “The Unfinished Hours” was illuminated by two outstanding painters, Enguerrand Quarton and Barthélemy d’Eyck. Though much of the decoration was left incomplete, the artists’ intentions are indicated by sketches, notes, and blank spaces.

“The Unfinished Hours”: MS M.358, fol. 19. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837-1913) in 1909.

Morganmobile: Rough Drafts

Years before his 1919 appointment as a printmaking master at the Bauhaus, Lyonel Feininger was an influential cartoonist for American newspapers. On a page of seemingly dashed-off pencil drawings, he relayed the sequential movements of a girl whose oversized feet signal the awkward physicality of adolescence.

Lyonel Feininger (American-German, 1871–-1956), Three Studies of a School Girl Playing Diabolo, 1907, graphite on hole-punched paper. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Ralph Colin, 1974.67:5. © Lyonel Feininger / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Morganmobile: Rough Drafts

William Morris designed every letter and printed border for the books published by his Kelmscott Press. Here he drafts the form of a lowercase h, shaping and reshaping the curved bowl where it attaches to the vertical ascender. His notes indicate he is still unhappy with the proportions of the serifs and the overall rigidity of the letterform.

William Morris (1834–1896), Type design for letter h. London, about 1890. Gift of John M. Crawford, Jr., 1975, PML 76897.

Morganmobile: Rough Drafts

At its most vivid, a photograph transports viewers into a real-world moment, such as Louis Faurer’s eye-to-eye meeting with skeptical twins on Fifth Avenue. But the artist’s heavily annotated working proof is a reminder that photographic prints, like other works of visual art, are products of patient trial and error.

Louis Faurer (American, 1916–2001): Fifth Avenue, New York, 1948. Working proof: grease pencil on gelatin silver print, before 1981. Gift of Chuck Kelton, 2017.304.

© Estate of Louis Faurer

Morganmobile: Rough Drafts

With a turbulent jumble of swift pen and brush lines, Anthony van Dyck tried out several possible ways of representing the mythical encounter between Diana, the Roman moon goddess, and the young shepherd Endymion, whom she cast into eternal sleep. On the left side of the sheet, overlapping strokes of varying thickness and length begin to coalesce into a coherent composition.

Anthony van Dyck (Flemish, 1599–1641), Diana and Endymion, ca. 1625–1627, pen and brown ink and wash, with white opaque watercolor, on blue laid paper, faded to green gray. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1909, I, 240.

Morganmobile: Rough Drafts

Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s script loops and tangles across the page as she works on the opening stanzas of a late poem, “A Musical Instrument." After six lines written in pen, the author appears to have left herself a space in which to draft more provisionally, in pencil, the next two lines: "He tears out a reed, the great god Pan / Out of the heart of the river.”

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806–1861), manuscript of Last Poems, undated. Purchased in 1945, MA 1211.

Morganmobile: Rough Drafts

Photographers edit the raw product of their camera work on contact sheets (reference images made by laying strips of film down on printing paper). Here a young Peter Hujar reveals his artistic instincts with crop-marks that will heighten the intimacy of his encounter with a cat in the streets of Sperlonga.

Peter Hujar (American, 1934–1987): Sperlonga, Italy, ca. 1963, gelatin silver print contact sheet. Purchased on the Charina Endowment Fund, 2013.108:8.5399-5402.

© The Peter Hujar Archive LLC, courtesy of Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

Morganmobile: Rough Drafts

Pianist Glenn Gould inscribed sheets of music to indicate which takes, or parts of takes, were to be used in the famously complex edit of his second recording of J. S. Bach's Goldberg Variations (CBS, 1982).

Glenn Gould (Canadian, 1932–1982). Johann Sebastian Bach (German, 1685–1750): Klavierübung, IV. Teil: Aria mit verschiedenen Veränderungen: Goldberg-Variationen. New York: C. F. Peters, 1937, p. 41. Mary Flagler Cary Music Collection. Edition Peters Group.

Morganmobile: Rough Drafts

Some bookbindings retain signs of frequent adaptation during their centuries of use and re-use. The fore-edge of this wood, parchment, cord, and rough-hewn deerskin binding bears remnants of an earlier structure, repurposed in the fourteenth century to provide protection for the textblock it still contains.

Aristotle, Metaphysicae, book 14: MS M.809. Purchased from Lathrop C. Harper, Inc., 1940.

Morganmobile: Rough Drafts

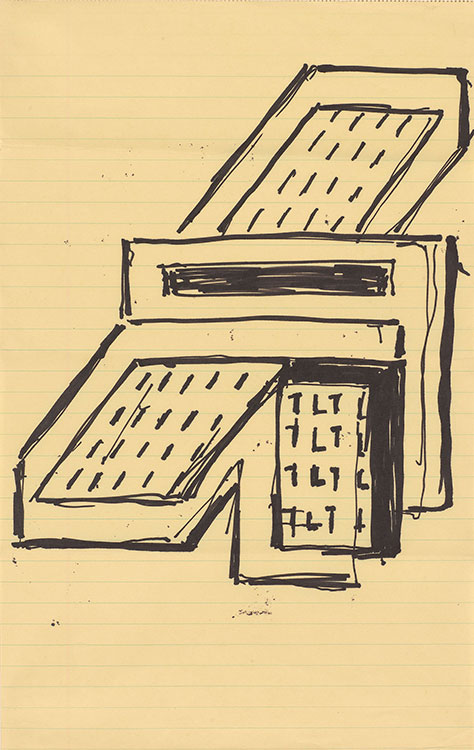

Frank Stella’s rough sketch, created on an ordinary sheet of yellow lined paper, appears to relate to his Polish Village series of paintings (1970–1973), which drew inspiration from the interlocking wooden architecture of traditional Polish synagogues.

Frank Stella (American, b. 1936), Untitled, ca. 1970–1973, marker on lined paper. Gift of James Corcoran; 2007.115.

© Frank Stella / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Morganmobile: Rough Drafts

The copperplate used to print this impression, barely two inches tall, dates from 1788—one of Blake’s earliest experiments in etching words and images in relief. It was made for a book of aphorisms, evidently set aside when he began etching the larger, more elaborate designs for Songs of Innocence. The earlier plates were not printed until 1794, after Blake had produced the Songs and most of his other illuminated masterpieces.

William Blake (1757–1827), There Is No Natural Religion ([London]: The author and printer W. Blake, [1788/94]). Gift of Mrs. Landon K. Thorne, 1973, PML 63940.1.

Morganmobile: Rough Drafts

Halfway down this page from a draft of The Picture of Dorian Gray, Oscar Wilde cut text from a scene between the painter Basil Hallward and Dorian. His edit mutes—momentarily—the homoerotic charge between artist and model. The words Wilde has crossed out are “And, as he leaned across to look at it, his hair just brushed my cheek (above: 'touched my hand'). The world becomes young to me when I hold his hand, as when I see him, the centuries yield up all their secrets!”

Oscar Wilde (1854–1900), manuscript draft of The Picture of Dorian Gray, ca. 1890. Purchased in 1913, MA 883.

Morganmobile: Rough Drafts

For composers laboring in the long shadow cast by Beethoven, producing more than nine symphonies became a sort of fateful test. Gustav Mahler died before completing his tenth, leaving much of it in draft form, including the fourth movement seen here. Although Deryck Cooke and others created performable versions after Mahler’s death, this partial score records a labor that never bore the full fruit of its creator.

Gustav Mahler (Austrian, 1860–1911): Symphony no. 10, fourth movement (sketches, detail), autograph manuscript, 1910. Morgan Collection.