Jean-Jacques Lequeu: Visionary Architect. Drawings from the Bibliothèque nationale de France

In 1825, after struggling for nearly a decade to find a buyer for his drawings, Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826) donated 823 sheets to the Print Department of the Royal Library in Paris. Although Lequeu defined himself as an architect and began his career working on building sites, he spent the majority of his life as a government draftsman shifting between bureaucratic offices before being forced to retire on a meager pension. His gift to the Royal Library reflected a hidden dimension of Lequeu’s draftsmanship. Throughout his life, he worked on his own, producing animated self-portraits, plans for revolutionary monuments, teaching manuals, explorations of the body, and over one hundred designs for visionary architectural projects. The drawings in his portfolio evince remarkable skill and creativity, an inventiveness inspired by both classical and contemporary writings, and the artist’s own vivid imagination.

Born during the reign of Louis XV (r. 1715–74), Lequeu was a witness to the death throes of the ancien régime, the upheavals brought about by the French Revolution, and the new order established under Napoleon’s empire. His work, created in solitude and fueled by self-study, reflects the opportunities and vicissitudes of his troubled times and a vision of architecture that defied academic boundaries.

This online exhibition was created in conjunction with the exhibition Jean-Jacques Lequeu: Visionary Architect on view January 31 through September 13, 2020.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu: Visionary Architect is organized by the Morgan Library & Museum and the Bibiliothèque nationale de France with the cooperation of Paris Musées.

The exhibition was presented at the Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris, from 11 December 2018 to 31 March 2019. Exhibition curators were Corinne Le Bitouzé and Christophe Leribault and scientific collaborators were Laurent Baridon, Jean-Philippe Garric, and Martial Guédron. The curator of the exhibition at the Morgan is Jennifer Tonkovich, Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator of Drawings and Prints.

The exhibition is made possible by generous support from the Pierre and Tana Matisse Foundation, an anonymous donor, the Alex Gordon Fund for Exhibitions, and Aso O. Tavitian, with assistance from Robert Dance and Hubert and Mireille Goldschmidt.

![]()

Colin B. Bailey: Hello, I'm Colin B. Bailey, director of The Morgan Library and Museum, and I'm delighted to welcome you to Jean-Jacques Lequeu, Visionary Architect Drawings from the Bibliothèque nationale de France. The drawings in this show are among the more than 800 sheets given by Lequeu shortly before his death in 1826 to the Royal Library in Paris, which later became the Bibliothèque nationale de France. For nearly two centuries, they have been preserved there, known only to a handful of scholars. This exhibition is the first devoted to Lequeu, and through a selection of his most compelling works, we hope to introduce you to this highly original and innovative draftsman who in many ways embodies the spirit of his troubled times, which spanned the Enlightenment, the French Revolution, and the Napoleonic period. As you move through the gallery, look for the audio symbols to discover commentary from the exhibition's curator, Jennifer Tonkovich, who provides further insights into the historical and artistic context of these extraordinary and beguiling drawings. Thank you for joining us at the Morgan. We hope you enjoy your visit.

Face-to-face with Lequeu

Lequeu’s donation to the Royal Library reveals his desire for recognition: it included notes for an autobiography, letters, newspaper articles, instructional essays and manuals, and a significant cache of self-portraits. He restricted the display of his 1792 self-portrait (shown nearby) until 1850. This focus on controlling the spread of his work indicates a concern for his legacy, which consisted largely of his drawings.

Spanning the range of his career, Lequeu’s self-portraits give a sense of the artist as an individual, one whose adaptability served him well during an era of political upheaval. Lequeu offered portrayals of himself as an intellectual, formally posed among his books, and as a citizen, informally attired and in profile. He also used himself as a model for a series of physiognomic studies exploring comic and dramatic expressions of emotion. These works underscore Lequeu’s complex persona and hint at the broad range of his interests, which extended far beyond inventive architectural designs.

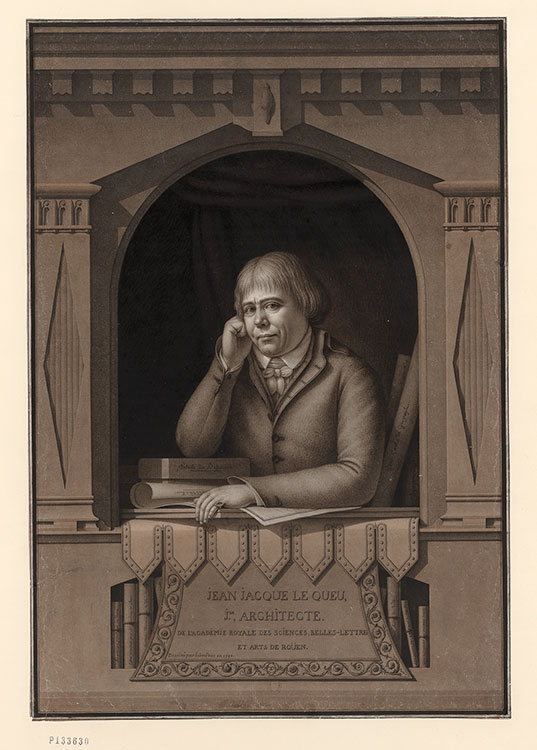

Self-portrait (Jean-Jacques Lequeu Reflecting)

In the 1822 catalogue he prepared for the sale of his drawings, Lequeu described himself as “reflecting” in this self-portrait. Seated in a niche, he pauses in his studies. He is surrounded by his accomplishments, including the new map of Paris upon which he rests his arm. The inscription identifies him as an architect of the Rouen Academy, but the elements surrounding him deviate significantly from academic tradition and indicate his personal style as a designer. The pilasters contain fluted diamond-shaped panels that match his signet ring, while the keystone above him is adorned with a beaver, a natural builder.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Self-Portrait (Jean-Jacques Lequeu Reflecting), 1792

Pen and black and brown ink, brown and gray wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

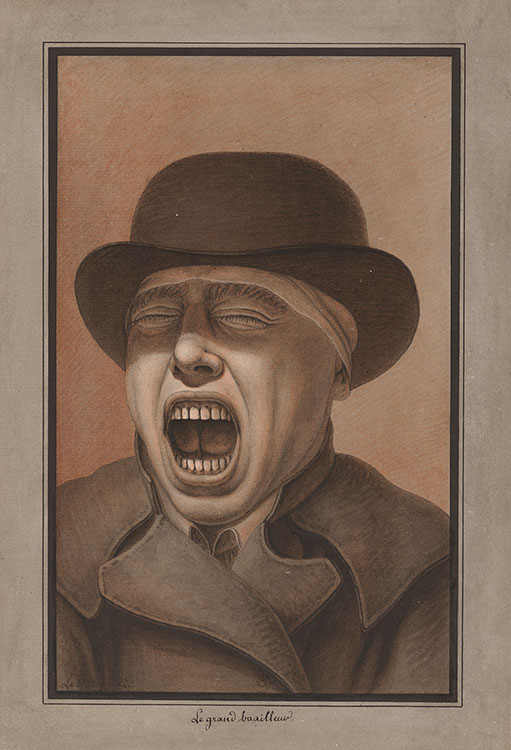

The Great Yawner

Lequeu inserted an additional a into the French word bailleur (yawner) identifying this man with his mouth agape, perhaps to echo the sound of a prolonged yawn. The artist was likely familiar with contemporary depictions of the subject, such as a 1783 self-portrait by Joseph Ducreux (1735–1802) in which he is shown midyawn and Franz Xaver Messerschmidt’s 1781–83 bronze head of a yawning man.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

The Great Yawner

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, red chalk

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Squinting Man

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Squinting Man

Red chalk and wash, brown ink

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Pouting Man

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Pouting Man

Pen and black ink, brown wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Jennifer Tonkovich: Welcome to Jean-Jacques Lequeu: Visionary Architect. Drawings from the Bibliothèque nationale de France. This is Jennifer Tonkovich, the Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator of Drawings and Prints here at The Morgan Library & Museum. Lequeu left us a paper legacy of more than 800 drawings, and among them are several sheets in which he used himself as the model. These self-portraits feed our curiosity about the individual behind this large and strange group of works. These drawings not only capture the artist's appearance, but also alert us to how he wanted to be seen. An informal profile portrait shows us a smiling Lequeu. In fact, he would've had to work with a friend in order to trace his profile. He heartily approved of this particular portrait, noting that it was a good likeness. In a more formal self-portrait, he poses as an architect from Rouen who wants to be seen and remembered as an educated professional, well-groomed, reflective, and surrounded by his work. Less straightforward is the striking series of physiognomic studies in which he depicts himself with exaggerated facial expressions. These works invite us to imagine him sitting in his modest apartment, looking at himself in a mirror, pulling faces and trying to capture them on the page. He preens, he pouts, he makes vulgar gestures, he's bare-chested or in tattered clothes. These solo performances raise compelling questions. Who was his imagined audience? Is Lequeu, who wrote several plays, acting for us? Are these meant to be amusing? What do we make about the poignant air of self-pity that arises from the mockery? We know Lequeu thought about the intimate nature of portraiture and how a likeness could also serve as an object of desire. In his writings, he wondered what would've happened "if I had been favored enough by nature, or rather happy enough, for a woman to desire the imitation of my features?"

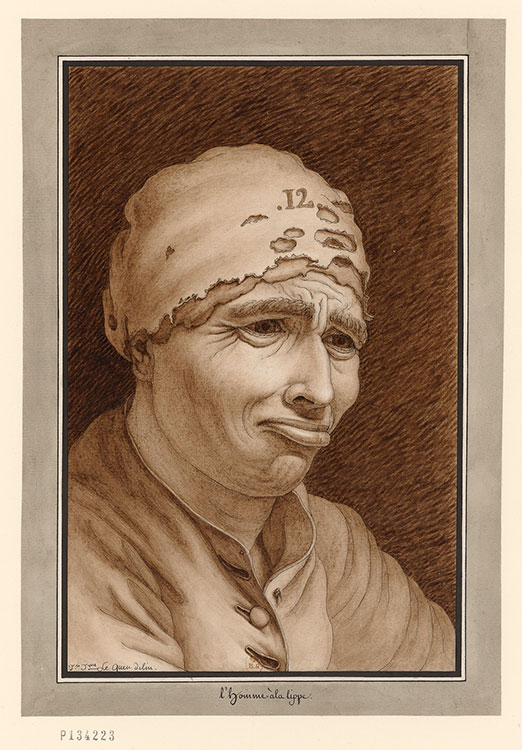

Preening Man

Lequeu’s careful studies of facial expressions also function as self-portraits, revealing the artist at different stages of life and in a range of moods. As with the character heads sculpted by Franz Xaver Messerschmidt (1736–1783) first exhibited in Vienna in 1793, Lequeu’s portraits examine how facial expressions convey not only fleeting emotions but also ingrained elements of a subject’s personality. Here, the bare- chested artist, his head wrapped in a flannel, puckers his lips and raises his brows in a parody of vanity.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Preening Man

Pen and black ink, brown wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

He Sticks Out His Tongue

Wearing an open-necked shirt and with his head shorn, a man opens his mouth wide to stick out his tongue, a bold and direct gesture that is striking in its vulgarity.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

He Sticks Out His Tongue

Pen and black ink, brown wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

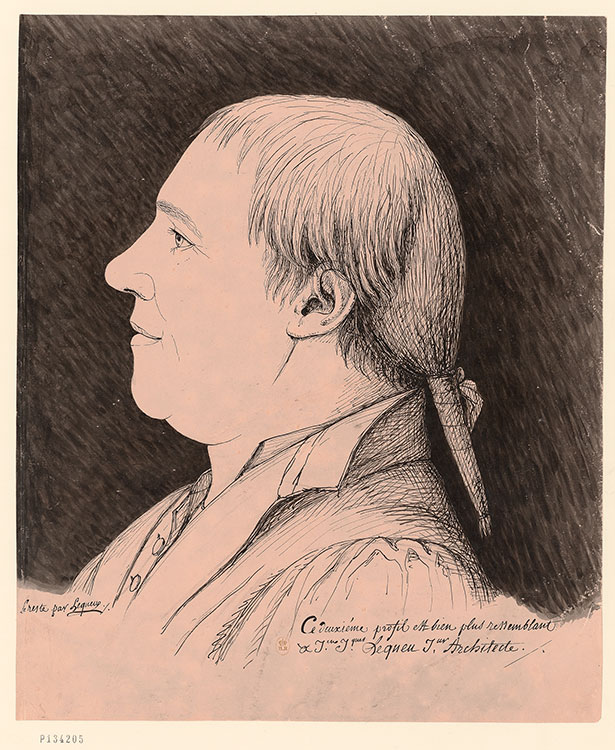

Self-portrait in Profile

Lequeu indicated in his inscription—“This second profile much more closely resembles Jean Jacques Lequeu Junior, Architect”—that he was pleased with this attempt at capturing his likeness, produced when he was thirty- six years old. In an open-necked shirt, his hair tied back with a cord, the artist appears at ease. The profile portrait, a popular style during the revolutionary era, harks back to ancient Roman coins, and Lequeu himself was a collector of coins and medals. To outline himself in profile, Lequeu likely relied on a physionotrace, a recently invented device for drawing silhouettes.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Self-Portrait in Profile, 1793

Pen and black ink and wash, over black chalk

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

An Architect in Practice and on Paper

After training at the Rouen Public School of Design, in 1779 Lequeu moved to Paris. He found work with the architect Jacques Germain Soufflot, an endeavor that came to an end with the master’s death the following year. He continued to work with Soufflot’s nephew François, overseeing construction at the Hôtel de Montholon. Before the revolution, Lequeu also pursued private patronage.

In 1792, Lequeu prepared a series of didactic studies to investigate the structural principles behind drawing the human head. The frontispiece to his New Method Applied to the Elementary Principles of Drawing, Tending to Graphically Perfect the Outline of the Human Head by Means of Various Geometric Figures announces his ambition to decipher antique ideals of beauty using modern tools and geometry.

Lequeu’s principal collection of drawings, grouped under the title Civil Architecture, was conceived originally as a textbook for the practice of architectural draftsmanship. It soon became a repository for a stunning range of designs that, unconstrained by the practicalities of construction, combined elements of humor, memory, and fantasy, often with extensive annotations. While Lequeu prepared the basic instructional drawings at the outset of his career, he continued adding to the collection for the rest of his life.

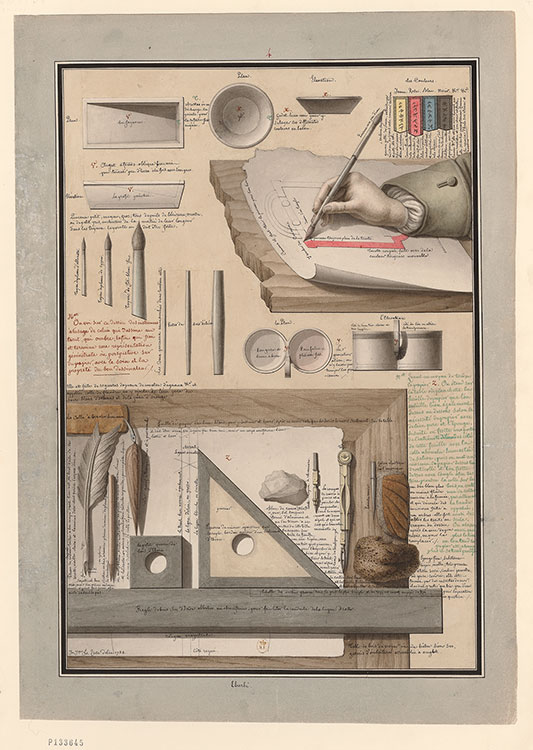

Draftsman’s Tools, from Civil Architecture

This sheet presents the draftsman’s arsenal: brushes, penholders, graphite, rulers, ruling pens, and erasers. In the accompanying text, Lequeu described his drawing process as a series of stages, beginning with contour lines and following with the addition of light and shadow. He was deeply conscious of the diverse sources of his materials, which, as his annotations indicate, came from as far as China, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and Siam (now Thailand).

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Draftsman’s Tools, from Civil Architecture, 1782

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Jennifer Tonkovich: Lequeu approached the production of his drawings with an almost ritual precision. He began by preparing the sheet of paper. He would soak it before stretching the sheet and adhering it to his drawing board. Water was applied with a natural sponge and the corners were tacked down with glue. Once the paper was ready, he would execute an initial trace or outline, often using drawing tools in order to make a straight line. Next, he applied a binder to set the ink outlines and ready the sheet for gouache. In this stage, he brushed on a solution of water and Roman alum or salt with a brush made from badger bristles. The astringent qualities of the alum mixture would keep the inked outlines from bleeding during the final step, the application of gouache, typically in brown or gray. To tint passages with watercolor, Lequeu relied on four pigments, yellow, rose, blue, and black, often combining and diluting the colors to pastel hues. Lequeu's interest in materials is further reflected in his annotations on his sheet. He includes a recipe for glue, calling for sheepskin flakes, white sugar from Orléans and orange peel, among other ingredients. He gives advice on how to select the best quill from a young and healthy crow, and marvels at how the rubber for his eraser originated in tree sap, revealing the painstaking attention he paid to every aspect of his process. You'll notice throughout the show that Lequeu carefully mounted his drawings, sometimes adding titles in a gothic or imitation Greek script. In some cases, the drawing can actually be lifted to reveal commentary on the mount behind the drawing or additional designs. This sensitive and sophisticated system reveals the meticulous care that went into the creation of each object.

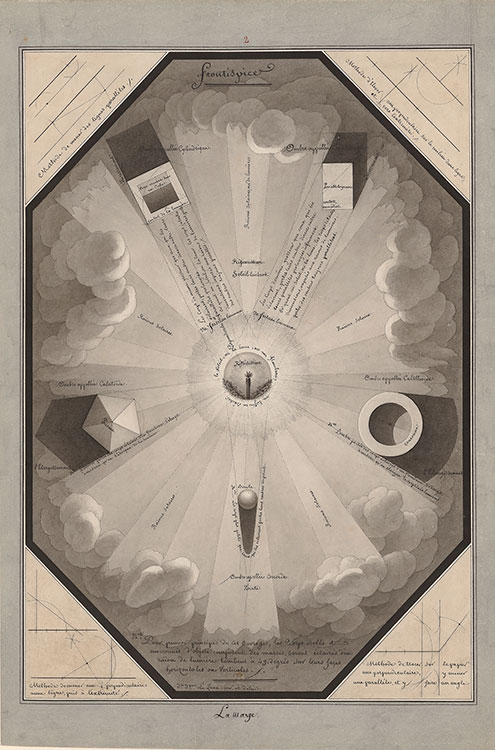

The Principle of Shadows, frontispiece to the Civil Architecture

In the 107 drawings that comprise his Civil Architecture, Lequeu offered methods for depicting three-dimensional forms, the architectures “of various peoples scattered on the Earth,” and his own inventions. He paid special attention to “shadows and their different effects projected on plans, elevations and profiles by the sunlight or burning bodies,” which was the subject of

a larger debate among contemporary architects.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

The Principle of Shadows, frontispiece to Civil Architecture, 1782

Pen and black ink, gray wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

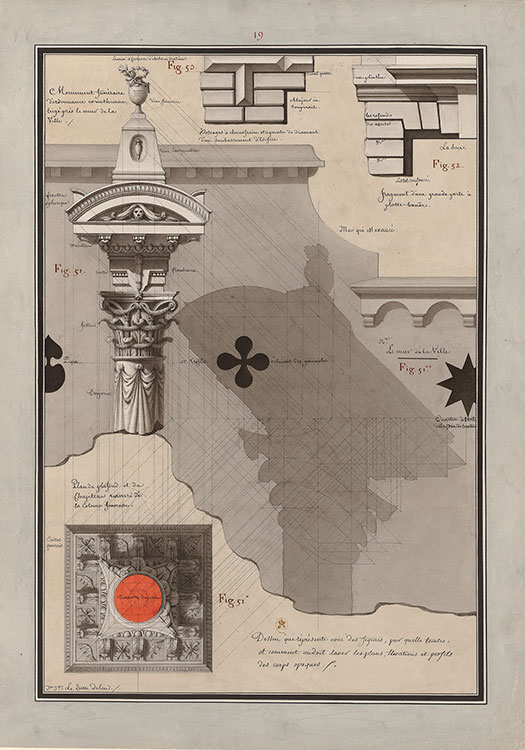

Funerary monument, from Civil Architecture

Through an agglomeration of architectural decoration, Lequeu transformed a Corinthian column into a funerary monument. Reminders of death and ancient sepulchral rituals abound: a ceremonial urn atop the column; an ancient tear vessel, or lachrymatory, below; and a skull in the pediment above a ceremonial torch. He even incorporated pairs of crossed tibias in the coffered decoration of the cornice seen in the plan at lower left. Most striking, however, is that a large part of the page is dominated not by the monument but by its shadow, which forms a shape that is both strange and ominous.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Funerary Monument, from Civil Architecture

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

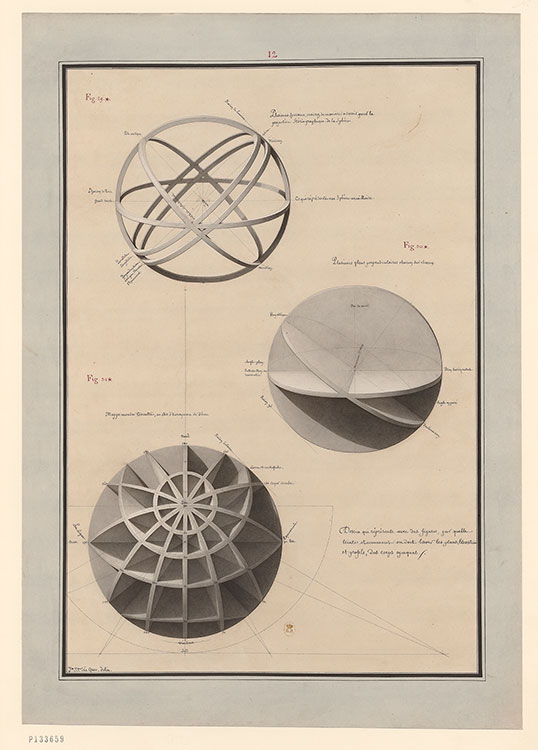

Study of Spheres, from Civil Architecture

Civil Architecture includes a number of didactic sheets outlining visual models for technical draftsmanship. This page offers instructions for creating volume and using light and shadow to define complex three-dimensional objects, like armillary spheres and terrestrial globes. The caption at bottom, “Globe of the Earth, or a framework of a dome,” reflects the wide range of subjects encompassed by Lequeu’s guidelines.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Study of Spheres, from Civil Architecture,

Pen and black ink, gray wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Jennifer Tonkovich: Lequeu mastered the art of modeling form using only the white of the paper and black ink in different concentrations. This type of shading was what he referred to as his black manor. He prided himself on his expertise with gouache and sought to become a proponent of this method of drawing. Teaching was a critical part of Lequeu's life. In the opening text for his civil architecture, he penned an address to lovers and friends of the arts with an offer to instruct them in his method. He describes his qualifications as an instructor: "Sir Lequeu, who studied architecture under enlightened masters at Rouen, having nothing so much at heart as to deserve the esteem and protection of the city of Paris, and to offer its citizens his services, announces an office where he will give drawing lessons, both of figure and of architectural ornament. Lequeu joins a knowledge of the plans and details of construction, which he does in his daily work and the drawing of the figure in ink in the black manor. Convinced that this bold genre might interest people whose taste for the fine arts animates them and makes them desire guidance in the use of gouache for drawings of portraits, landscapes, maps, and architecture, he will give them lessons." Despite his willingness, Lequeu did not attract sufficient students to support himself as a drawing instructor and spent the majority of his career working as a Draftsman for the Land Registry Office.

Frontispiece to the New Method

Lequeu used drawing to interrogate the ancient canon of beauty, epitomized in this sheet by a venerated Roman marble bust thought to represent ideal human proportions. He divided the head into its component parts as if it comprised masonry blocks; beneath, he placed an array of the draftsman’s tools.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Frontispiece to New Method, 1792

Pen and black ink, gray wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Study of Mouths, from New Method

Applying his methodical approach to proportions, Lequeu used a protractor to draw a mouth frontally and in profile. As diagrammed, the contour of lips drawn according to this method would be derived from a series of curved arches extrapolated from a sequence of fixed points. The commentary compares the sinuous line of a closed mouth to a cupid’s bow, evoking the “sweet melancholy smile” of Venus’s “perfect mouth.”

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Study of Mouths, from New Method, 1792

Pen and black ink, gray-brown wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

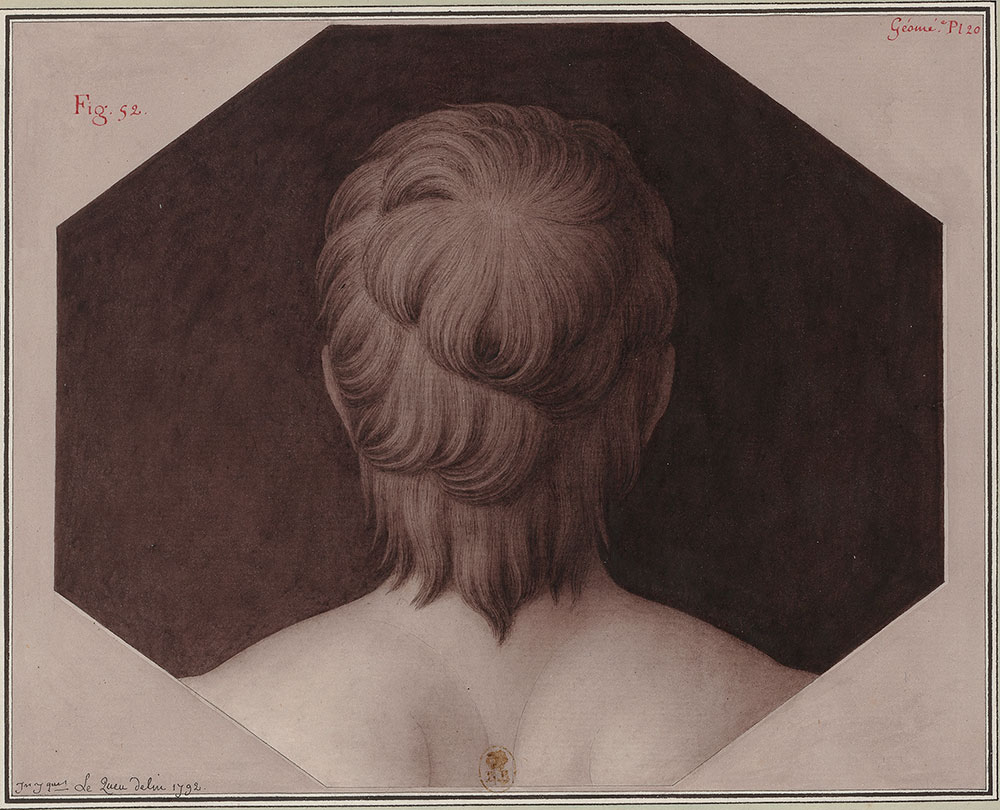

Study of a Head, from New Method

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Study of a Head, Seen from Behind, from

New Method, 1792

Pen and black ink, brown wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Study of a Head, Seen from Behind, from New Method

To understand the structure that underlies facial beauty and expressions, Lequeu studied the musculature of

the face and its geometric components. His notes on proportions indicate his familiarity with published anatomical texts. Lequeu’s commentary, however, ironically acknowledges the limitations of his method, noting that “it would be impossible to determine the true combination of passions on our face.”

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Study of a Head, from New Method, 1792

Pen and black ink, brown wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

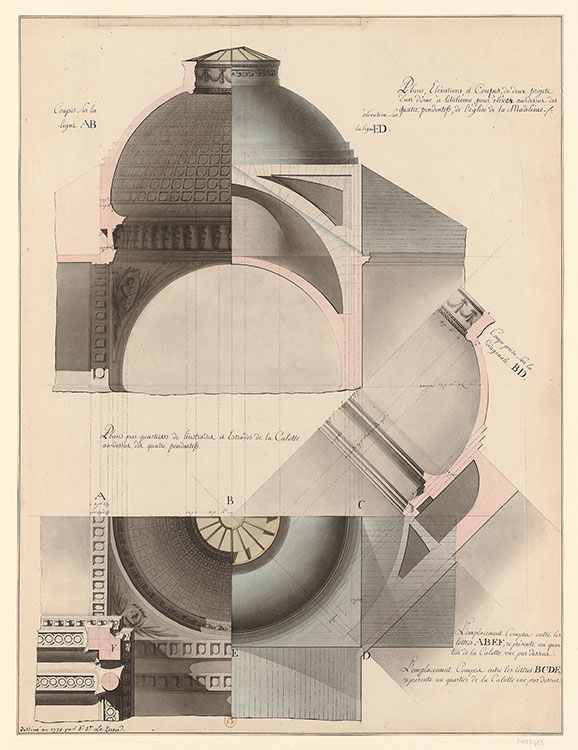

Proposal for the Dome of Sainte-Madeleine, Rouen

In 1773, the Rouen architect Jean Baptiste Le Brument was entrusted with building a chapel for the city’s hospital and proposed capping the building with a stone dome. Lequeu, who worked for Le Brument, drew a design for the stone dome from five different angles on this sheet. At lower left, it is outlined horizontally in a rectangular diagram, half viewed from underneath and half from above. This is elaborated in the upper registers, showing an exterior elevation and two cross- sections, with and without coffering. The designs are connected by dotted lines and corresponding letters,

inviting viewers to rotate the imaginary structure in their mind’s eye. (Ultimately, a lighter and less costly wooden- framed structure was adopted.)

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Proposal for the Dome of Sainte-Madeleine, Rouen, 1775

Pen and black ink, gray and brown wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

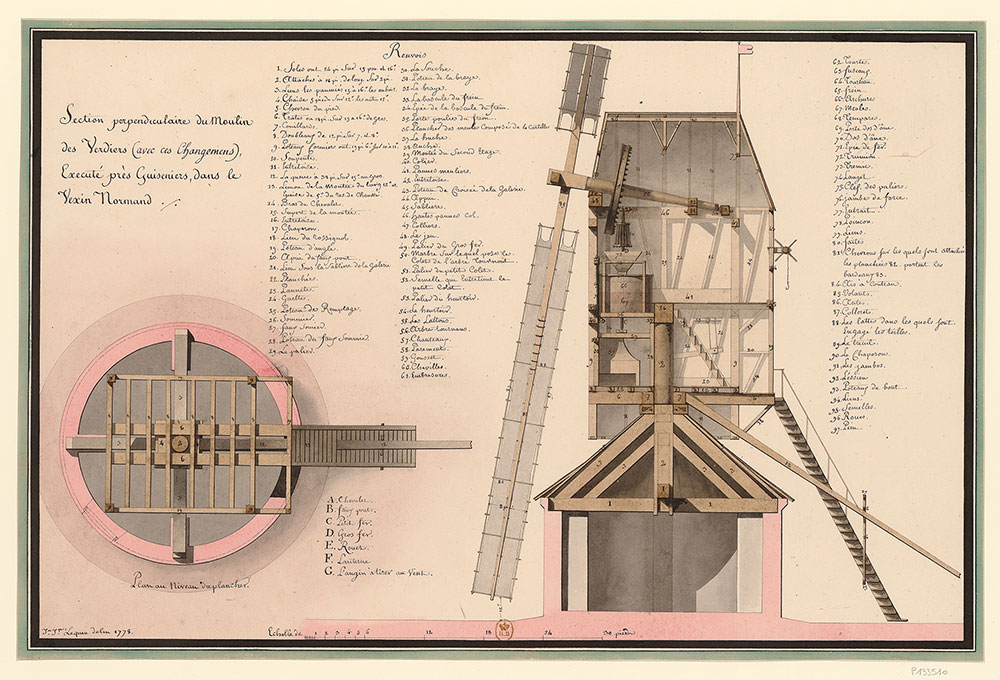

Perpendicular Section of the Verdiers Mill

The date of this design’s creation and the location

of the mill it depicts—the town of Guiseniers, between Rouen and Paris—suggest that Lequeu executed it during one of his frequent stays at his granduncle’s residence there. The detailed rendering and precisely numbered list of components elaborate on an illustration of rustic agriculture in Denis Diderot and Jean Le Rond d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie (1751–66), which Lequeu studied closely.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Perpendicular Section of the Verdiers Mill, 1778

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

A Stove for the Ceremonial Staircase at the hôtel de Montholon

Stoves, often used in place of fireplaces to heat structures, were frequently placed in thoroughfares where residents would not linger. Lequeu took this necessary but smoky feature as the basis for a meditation on architectural and bodily heat. A snaked column alludes to the famous serpentine tripod at Delphi, playfully comparing the hot air produced by the stove with oracular smoke. Above the firebox, the chaste goddess Diana holds an oil lamp suggestively, emphasizing the tension between the heat of desire and the virginity required to tend the temple fire.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

A Stove for the Ceremonial Staircase at the Hôtel de Montholon, 1785

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

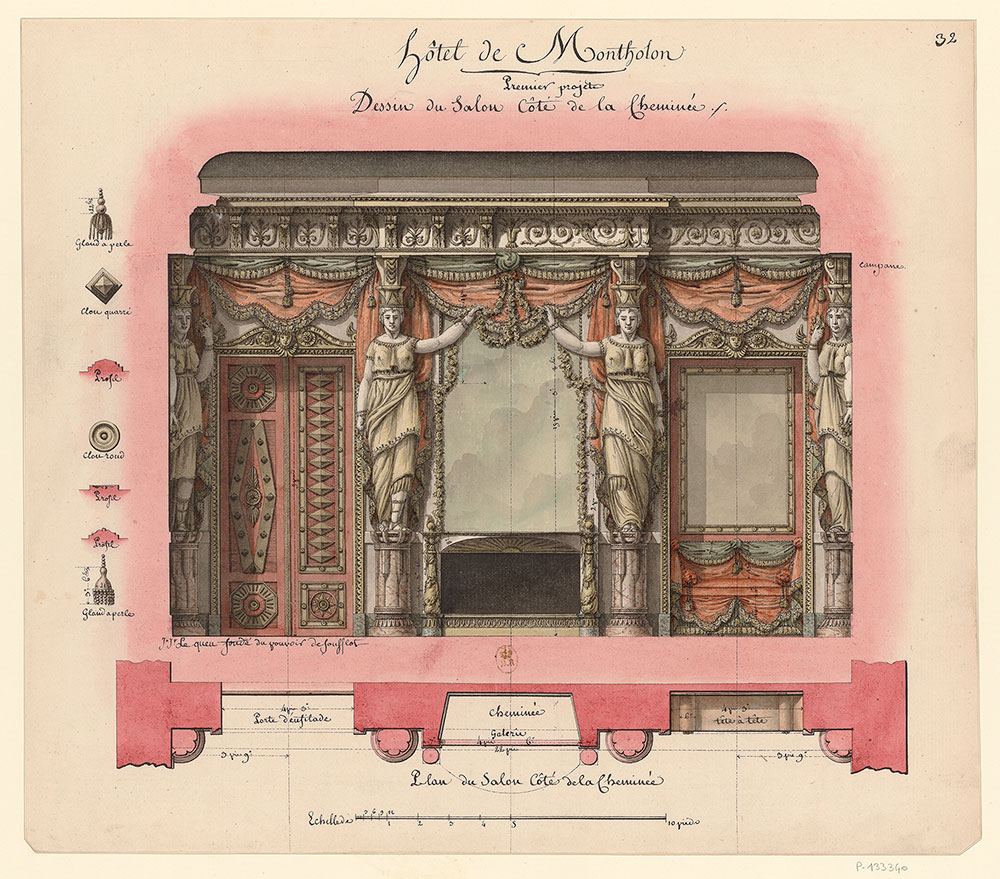

An Andiron for the hôtel de Montholon

The Hôtel de Montholon, built in 1785 by François Soufflot and still standing on one of the Grands Boulevards in northern Paris, is a rare example of a sumptuous neoclassical mansion of the eighteenth century. Lequeu was appointed site foreman, in charge of its construction and interior design. This unrealized design for a living room is dominated by a pair of caryatids, sculptural columns in the form of young women thought to have been enslaved symbolically as architectural supports.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Design for a Living Room at the Hôtel de Montholon, 1785

Pen and black ink, gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Design for a Living Room at the hôtel de Montholon

The Hôtel de Montholon, built in 1785 by François Soufflot and still standing on one of the Grands Boulevards in northern Paris, is a rare example of a sumptuous neoclassical mansion of the eighteenth century. Lequeu was appointed site foreman, in charge of its construction and interior design. This unrealized design for a living room is dominated by a pair of caryatids, sculptural columns in the form of young women thought to have been enslaved symbolically as architectural supports.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Design for a Living Room at the Hôtel de Montholon, 1785

Pen and black ink, gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Façade of a Pleasure Palace, called the Temple of Silence

In an effort to establish his architectural career, Lequeu courted aristocratic clients with designs for country residences in the waning moments of the ancien régime. Construction began on a villa in Rouen for one patron, Louis-Jacques Grossin, comte de Bouville, but the project was halted by the revolution and the count’s flight from France. That this intimate villa was conceived as a Temple of Silence is indicated by the figure of Harpocrates, the Hellenistic god of secrets, in the tympanum. The design was included in an 1813 publication on civil architecture by Lequeu’s friend Jean-Charles Krafft, suggesting contemporary awareness of the artist’s work.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Façade of a Pleasure Palace, Called the Temple of Silence, 1788

Pen and black ink, brown wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Jennifer Tonkovich: Early in his career, Lequeu used his connections in Rouen to seek private patronage and generate commissions. He befriended a local aristocrat, the Count of Bouville, and in 1780 to '82, when Lequeu was roughly 24 years old, he claimed to have taken a trip to Italy with his patron. The evidence is a diary of the trip later produced by Lequeu, although scholars argue that it's equally likely the diary was a fabrication, and Lequeu never left France. Lequeu's written log outlines their fictional voyage. They depart Paris, pass through Lyon and the south of France, before arriving in Genoa. From there, they embark on a whirlwind tour of Italy's picturesque destinations, visiting Pisa, Florence, Rome, Naples, Bologna, Venice, Padua, Milan, and Turin, before returning home. Lequeu's entries describe their avid sightseeing and offer useful advice regarding how many days were needed to see each city and its highlights, how to get around, and what a decent room for the night might cost. Here's a passage from one of his entries in Rome. "In the Strada della Croce is a hostel, where it's very lovely to stay. You pay eight sol a day and you eat at the communal table. In Rome, there are people and books which inform travelers about the interesting things to see, and there are a greater number of them here than anywhere. For 30 sol, you can get a guide to each palace." Lequeu may have had nostalgia for the idea of a Roman holiday, as a few years later it would be untenable to travel with an aristocratic patron such as Bouville, whose career was suspended with the Revolution in 1789, and only resumed after the downfall of Napoleon in 1815.

Revolutionary Ambitions

The French Revolution heralded commissions for patriotic monuments commemorating the newly established republic. In 1794, Lequeu submitted five designs to competitions for major civic projects. Although some of his proposals were publicly exhibited, none were selected to be built.

Lequeu embraced revolutionary iconography and became a member of the National Guard and the Popular and Republican Society of the Arts, a patriotic assembly that espoused the ideology of the Reign of Terror. His precise political beliefs, however, are difficult to discern. Lequeu’s designs for projects celebrating revolutionary ideals are rich in detail but also humorous and occasionally ironic.

Symbolic Order for a State Room of a National Palace

Emblematic of the ancien régime, the aristocrat was a subject of scorn during the revolution, when many nobles fled France under the threat of the guillotine. Lequeu’s design for a column comprising an aristocrat with shackled wrists punishes the former ruling class in effigy: the noble, denied liberty, is forced to support the weight of the building. This overtly political design

testifies to Lequeu’s active production of revolutionary iconography.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Symbolic Order for the State Room of a National Palace, 1789

Pen and black ink, gray-brown wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Tomb of Isocrates, Athenian Orator

Turning to another ancient source—Plutarch’s Lives of the Ten Orators—Lequeu transcribed a description of the rhetorician Isocrates’s tomb and rendered a fantastic vision of its appearance. While the original tomb was surmounted by a column bearing a mermaid, symbolizing Isocrates’s eloquence, a mistranslation of the original Greek led Lequeu to include a sheep as the base.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Tomb of Isocrates, Athenian Orator, 1789

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

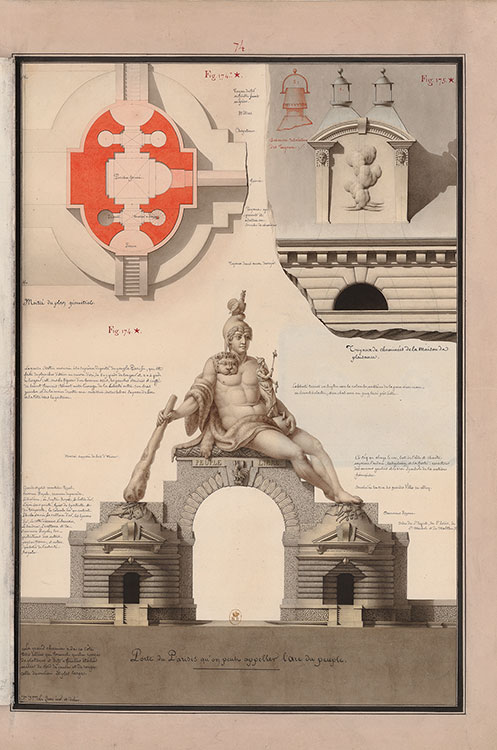

The Gate of Parisis, from Civil Architecture

This proposal for a monumental entrance gate honoring the Celtic tribe that gave Paris its name was exhibited in the Hall of Liberty shortly before the Reign of Terror ended in 1794. It is dense with republican imagery. Atop an arch, a colossal figure of the Gallic Hercules wears a Phrygian cap, surmounted by a Gallic rooster, as he holds a statue of Liberty standing on a globe. Yet Lequeu’s apparent support for the revolution cannot be taken at face value. On the back of the drawing, he wrote, “A drawing to save me from the guillotine. Everything for the fatherland.”

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

The Gate of Parisis, from Civil Architecture, 1794

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Aqueduct Transporting Water to the Holy City, from Civil Architecture

This imaginary aqueduct was meant to provide the “most limpid virgin pure water to the Sacred City.” At left is a Tower of Liberty and at right a “republican road,” and beneath the arcade are paths for pedestrians and carriages. The tower is embellished with symbols of independence and liberation. At left, in a diagram of the cornice, the artist calls for decorating the frieze with cat’s heads; the feline was Lequeu’s favorite avatar

of freedom.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Aqueduct Transporting Water to the Holy City, from Civil Architecture, ca. 1800–1804

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Monument to the Glory of Illustrious Men, for the Place de la Victoire, from Civil Architecture

In year II of the republican calendar (1793–94), a competition was held to design a monument commemorating those who had died on 10 August 1792 while storming the Tuileries Palace to depose the king. Lequeu witnessed the celebrations organized in their honor, and some of his marginal inscriptions on this entry are copied from the ephemeral monument erected outside the ruined palace at that time. Even though Lequeu’s design was exhibited in the Hall of Liberty—the assembly room of the Revolutionary Tribunal at the Conciergerie prison—the project was abandoned after Maximilien Robespierre’s dramatic fall from power in July 1794.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Monument to the Glory of Illustrious Men, for the Place de la Victoire, from Civil Architecture, 1794

Pen and black ink, gray-blue wash, pen and red ink, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Jennifer Tonkovich: For most of the 18th century, French artists enjoyed the patronage of the king and the aristocracy, but these sources of support were dramatically affected by the Revolution when the king was executed, along with many of the aristocrats who hadn't already fled France. Some artists took sides in the political upheaval, such as the painter Jacques-Louis David, whose friendship with Robespierre eventually landed him in prison. Others saw their careers founder or flourished, based on their allegiance. Many who were closely associated with the Ancien Régime left Paris to find work abroad. Remarkably, Lequeu navigated the changing cultural landscape, having only briefly worked with private aristocratic patrons before the Revolution. After a period of insecurity, he focused his energy on teaching, while participating in revolutionary competitions and securing a position with the new government's land registry office. The rest of his mature career unfolded under Napoleon's leadership. This made him part of the new order, which lasted until Napoleon's final downfall at Waterloo in 1815. Lequeu was forced into retirement that year, which marked the return of the monarchy and the start of the Bourbon Restoration. This design for a monument celebrating the martyrs of the Revolution shows Lequeu rallying to the revolutionary cause. But is this from professional expediency, or a reflection of his personal, political sympathies? On the verso, the artist scrawled a comment referring to the 1790s as "the time when human victims were sacrificed to liberty". And on the back of a design for a city gate displayed nearby, he claimed that it "saved me from the guillotine". These remarks, even if in jest, reveal a keen awareness that art and politics could be a matter of life and death.

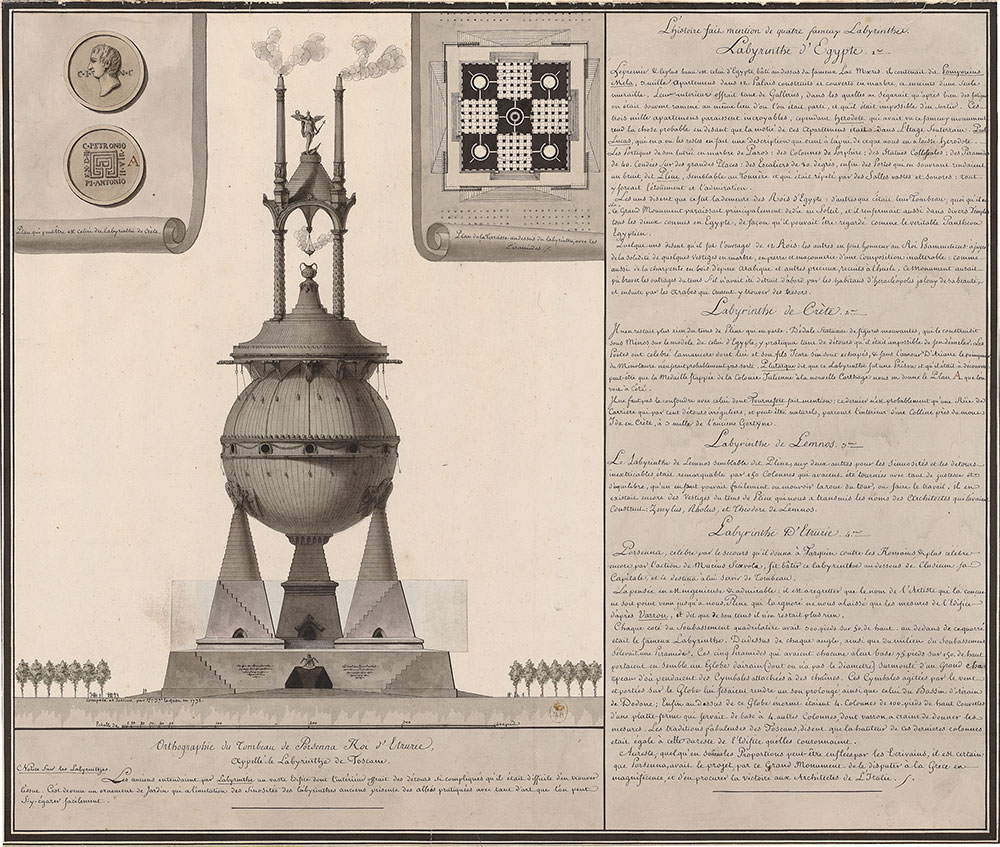

Etruscan Labyrinth

Intrigued by subterranean labyrinths, Lequeu here envisaged the legendary tomb of the Etruscan king Lars Porsena said to have been built around 500 BCE in Chiusi, Italy. Erected above an inescapable labyrinth, the massive structure boasted tiers of pyramids surmounted by a globe and adorned with bells that sounded in the wind. The scale of the monument is evident from the miniscule figures beneath the trees. At upper left is a rendering of a Roman coin struck in Spain; Lequeu interpreted its design as the mythical labyrinth of the Cretan king Minos. At right, Lequeu provided a compendium of ancient labyrinths based on descriptions from Herodotus and Pliny as well as contemporary travel literature.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Etruscan Labyrinth, 1792

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, patch with revision at base of monument

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

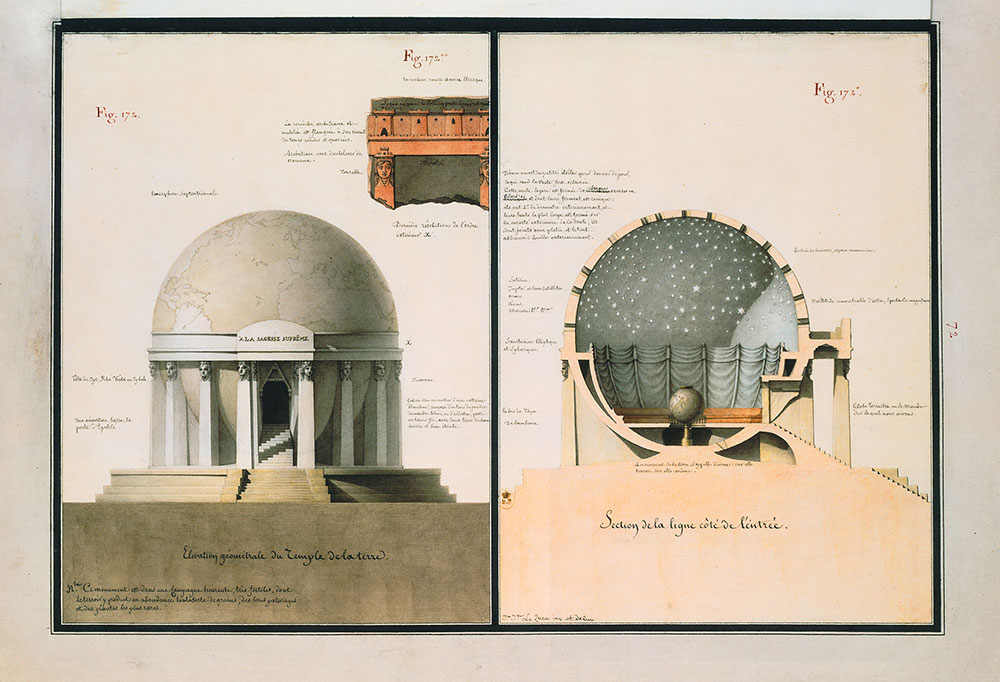

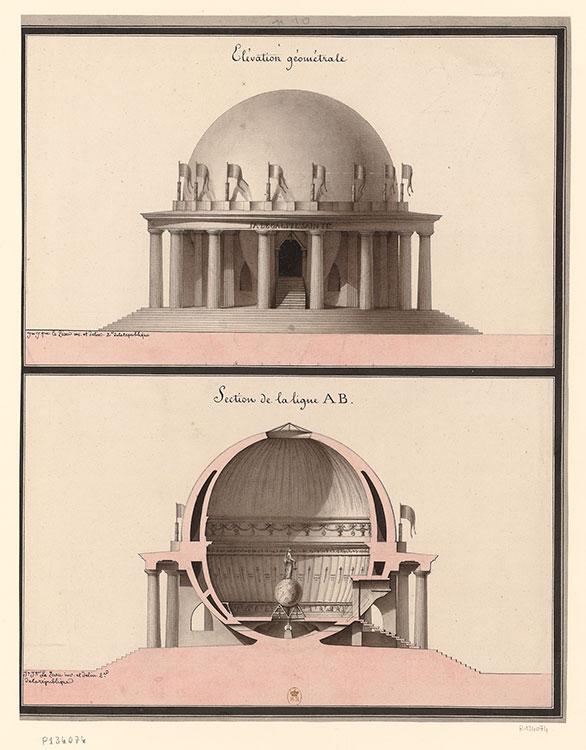

Design for a Temple of the Earth, from Civil Architecture

Intrigued by celestial and terrestrial globes, Lequeu frequently employed spheres in his designs. This example reinvents the artist’s Temple of Equality (displayed nearby) but takes the earth as its subject. At center would be a “magnificent spectacle of a planetary model . . . Surrounded by the dome’s representation of the celestial firmament.” Lequeu initially submitted the design to the revolutionary authorities in 1794, but his proposal was unsuccessful. In 1819–20, under the Restoration, he recycled the plan for a competition to design a chapel dedicated to St. Louis in Père-Lachaise Cemetery. After it was rejected again, Lequeu included the drawing in his Civil Architecture as a Temple of the Earth.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Design for a Temple of the Earth, from Civil Architecture, 1794

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

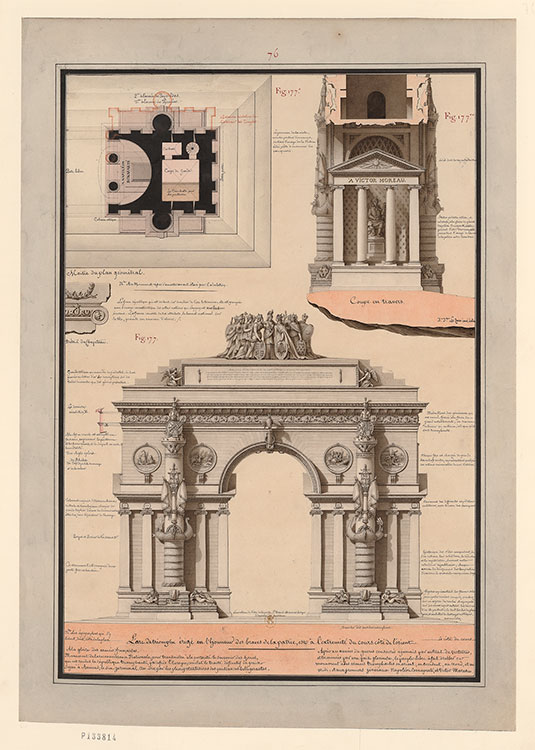

Proposal for the Completion of the Arc de Triomphe de l’Étoile, from Civil Architecture

Following his victory at the Battle of Austerlitz in 1805, Napoleon decided to build a monument to the glory of his Grande Armée. The Arc de Triomphe was erected up to the level of the vaults by Jean-François-Thérèse Chalgrin, but construction slowed when he died in 1811. Lequeu’s subsequent proposal sought a solution for the design during the intermediary period before the project resumed in 1823. He transformed the two piers into separate military towers, one on the left for soldiers of the newly restored Louis XVIII’s army and the other for the commanding generals and officers, with a monumental statue of the king situated in between.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Proposal for the Completion of the Arc de Triomphe de l’Étoile, from Civil Architecture, 1815–23

Pen and black ink, brown wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

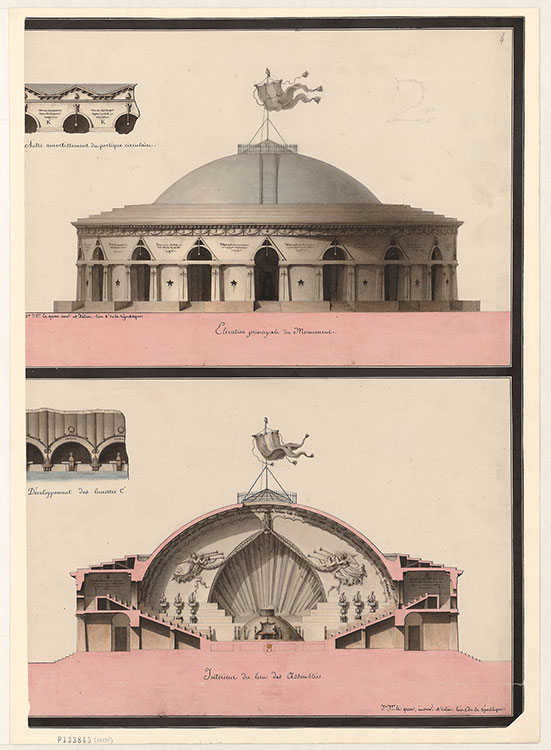

Design for an Assembly Hall

The revolutionary constitution ratified 24 June 1793 (year I) established Primary Assemblies, each comprising between two hundred and six hundred citizens who would gather to vote, although this process was never implemented. Among the welter of architectural competitions in 1794 was one to

commemorate the constitution with a space for these assemblies. In his proposal for an assembly hall, Lequeu transformed Nicolas Le Camus de Mézières’s Paris Corn Exchange (1763–69) into a grand arena, circular in plan, capped with a soaring dome, and illuminated by an oculus.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Design for an Assembly Hall, 1794

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Scene from the Tragedy of Virginia

This design for a theater set was inspired by a 1793 edition of the play Virginie by Jean-François de La Harpe (1739–1803), a passage from which Lequeu copied on the verso of the sheet. As recounted by the ancient writer Livy in his history of Rome, Virginia’s father stabbed her to death to prevent her capture by the lustful Appius Claudius, who claimed she was a fugitive slave from his own estate. Her murder inspired Roman plebeians to revolt against a patrician tribunal. The revolutionary overtones of the subject undoubtedly appealed to Lequeu, who set the tragic action at left in front of a grand vaulted space reminiscent of the cloaca maxima—the Roman sewer—which underscores the theme of the decay of justice.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Scene from the Tragedy of Virginia, 1794–95

Pen and black ink, brown wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Apotheosis of Trajan

This scene envisages a Roman ceremony marking the deification of the deceased Emperor Trajan in 117 CE. It shows a colossal burning pyre surmounted by a wax effigy of the emperor being kissed by his successor. Lequeu turned to contemporary sources for details as he envisioned the ancient ritual.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Apotheosis of Trajan, after 1802 (inscribed 1794)

Pen and black ink, brown wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Jennifer Tonkovich: At the time of his death, Lequeu owned an impressive library containing over 240 titles. The posthumous inventory of his apartment includes a list of books that comprise an intellectual portrait of the artist. His regular and intensive use of these sources is reflected in the copious writings on his drawings. One thing is evident, he was a bookworm. If we imagine ourselves in his studio among the bindings, we would find many classic works on architecture from tomes by the ancient Roman Vitruvius to the Italian Renaissance master, Andrea Palladio. He also own standard texts by contemporary French architects, such as Jean-François Blondel. Reflecting his polymath curiosity, he amassed volumes devoted to chemistry, mathematics, gardening, and the antiquities of Herculaneum. An avid reader of literature as well, he had editions of Michel de Montaigne's introspective essays, Jean de Lafontaine's amusing fables, and an 1804 French edition of the illustrated erotic masterpiece of the Italian Renaissance, The Dream of Poliphilo by Vittorio Colonna. Lequeu also had access to a number of reference works and encyclopedias, and he was familiar with the many volumes of Diderot and d'Alembert's famous Encyclopédie. He was not shy about cracking open the binding on more scandalous titles, including Richard Payne Knight's illustrated exploration of The Ancient Cult of Priapus, the God of Fertility. All of these works helped fuel Lequeu's remarkable creations on paper and continue to inspire a sense of kinship with those whose imaginations are spurred by a good book.

Design for a Temple of Equality

Lequeu prepared this design for a temple in the former aristocratic garden adjacent to the Paris mansion of banker Nicolas Beaujon (now the Élysée Palace) in 1794. He had joined the Popular and Republican Society of the Arts that year, and members were required to demonstrate a refined form of patriotism—likely the reason Lequeu dedicated the temple to Equality. Lequeu adapted the spherical structure from a model popularized by Antoine Laurent Thomas Vaudoyer’s 1782 design for a globular house.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Design for a Temple of Equality, 1794

Pen and black ink, gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Proposal for an Arch Celebrating the Treaty of Amiens, from Civil Architecture

The Treaty of Amiens, signed by England and France in 1802, created a peaceful interlude during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. A subsequent decree called for proposals for public art to commemorate the truce; the submitted designs would be exhibited for a month in the Gallery of Apollo at the Louvre. In Lequeu’s response, the Ionic capitals in the tower at left are embedded with hearts and rooster heads evoking the fighting cock of Rhodes, an animal celebrated by the ancients for its spirit and a symbol of courage and valor for the victorious French.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Proposal for an Arch Celebrating the Treaty of Amiens, from Civil Architecture, 1802–3

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Erotic Imagination

When Lequeu’s drawings entered the Royal Library, twenty-seven sheets with “lascivious and obscene” subjects were relegated to the restricted access division, later dubbed Hell (L’Enfer). Born in an era that celebrated libertinism, investigations of sexuality, and antiquities with erotic subjects, Lequeu created works ranging from explicit anatomical studies to suggestive juxtapositions of flesh and stone.

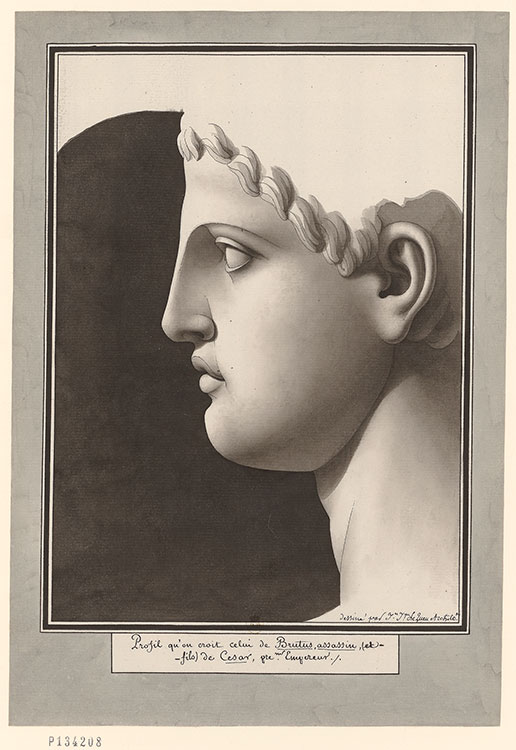

Brutus, the Assassin and Son of Caesar

This sculptural profile drawing depicts Brutus, whom Lequeu’s inscription describes in terms of his role in the assassination of his adopted father Julius Caesar. Identified by Lequeu as the “first emperor,” Caesar was proclaimed dictator for life in February of 44 BCE but was murdered soon after by senators who felt such a move threatened the the Roman republic. Revolutionaries in France celebrated Brutus as a virtuous republican who put his convictions in support of the state ahead of his love for his father.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Brutus, the Assassin and Son of Caesar, ca. 1792

Pen and black ink, black and gray wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Agdistis, Son of Jupiter

Lequeu was intrigued by the concept of gender fluidity. His interest led him to depict a rarely discussed figure from a 1727 mythological dictionary: Agdistis, born of the gods Jupiter and Cybele, who had both male and female physical attribut es and was castrated by the gods. Lequeu showed the young deity frontally, with breasts and male genitalia. The figure holds a rose and an arrow-shaped lightning bolt, alluding to the female and male sexual organs.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Agdistis, Son of Jupiter, ca. 1794–95

Pen and black ink, black and gray wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

The Bacchante

Lequeu’s explorations of amorous themes are often amusing. Seen from behind, a woman wearing an ivy wreath positions an aulos, a wind instrument used during feasts, suggestively near her backside. An inscription in Greek identifies her as one of the bacchantes, female companions of Bacchus, the god of wine, who indulged in frenzied trances while possessed by the wild power of nature. Her face, seen in profile, resembles a theatrical mask—a reminder that classical stage performances originated in bacchic rituals.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

The Bacchante, ca. 1798

Pen and black ink, black and gray-brown wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

He Is Free

This curious scene considers the association between liberation and libertine architecture. A nude woman, lying on her back in a gravity-defying pose, extends her upper body from a niche to free a male lyrebird; the first specimens of this bird, native to Australia, had just reached Europe. Below the niche, four melancholy masks frame the title. The contrast between the woman’s soft, curved body and the sharp, rigid stone surround produces an erotic tension.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

He Is Free, 1798–99

Pen and black ink, brown and red wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

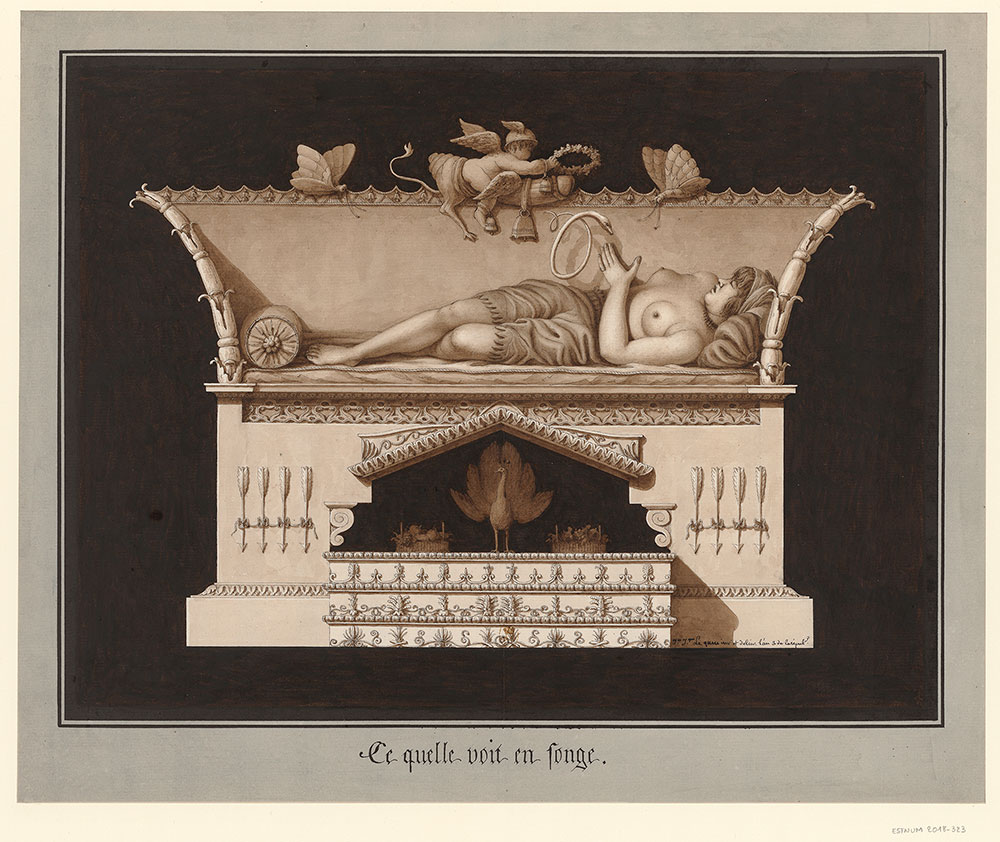

What She Sees in a Dream

Here, Lequeu visualized a young woman experiencing an erotic dream. She lies asleep on a sofa above an elaborate alcove housing a peacock and baskets with fruits and flowers. Other imagery evoking male genitalia, including arrows, acanthus shoots, and a winged cupid riding a phallus, surrounds her.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

What She Sees in a Dream, 1794–95

Pen and black ink, brown and black wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Alcove Window

Voyeurism, a motif throughout Lequeu’s designs, is explored explicitly in this nude. Through the bull’s-eye window of an alcove, the viewer gazes at a turbaned woman, eyes downcast and unaware of an observer’s presence, as she holds a mirror. The pointed ornament surrounding the opening is echoed in the antique-like relief on the mirror, which depicts a cupid holding a mirror decorated with a standing figure. This infinitely recurring effect visualizes voyeurism as an insatiable quest that both tantalizes beholders and separates them from the objects of their desire.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Alcove Window, 1797–98

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

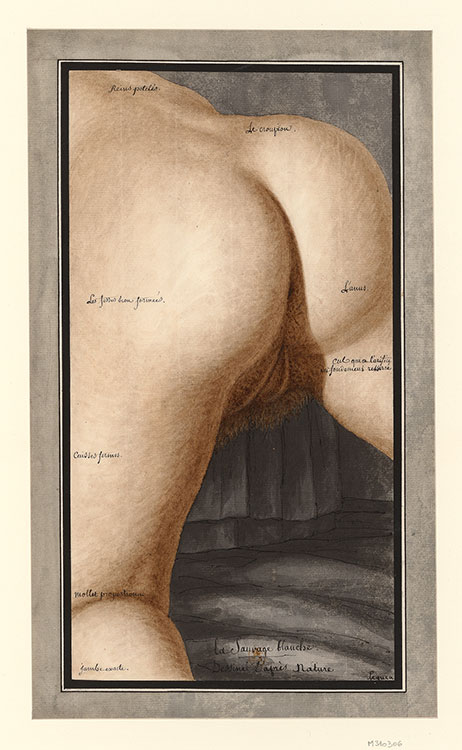

The White Savage

Lequeu’s provocatively titled, objectifying study of female buttocks combines near-clinical accuracy with pornographic intent. He labeled parts of the body (“the anus,” “the rump”) while commenting on the physical attributes of his model (“well-formed buttocks,” “firm thighs”). This type of sheet, drawn from life, might have been created in sessions like the one Lequeu described in a 1795 account of his whereabouts during a royalist uprising: “At nine o’clock the citizens Anne-Marie- Catherine Remy and Françoise Thouvenin . . . came to my place to model [and] I occupied myself by drawing several attitudes until three in the afternoon.”

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

The White Savage, ca. 1795

Pen and black ink, gray and brown wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

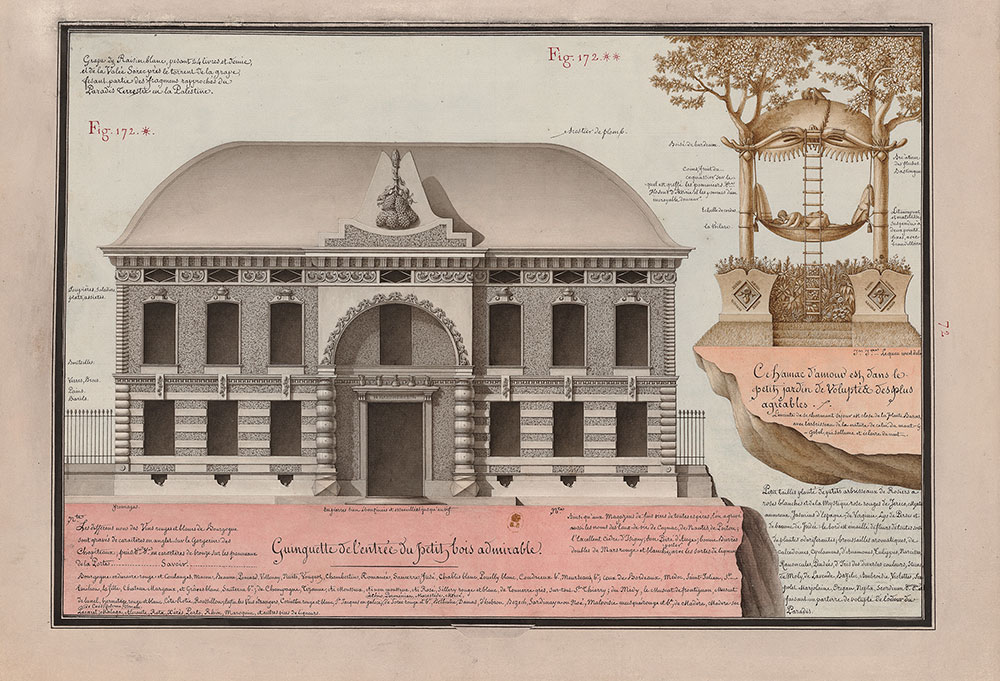

Tavern and Hammock of Love, from Civil Architecture

Lequeu’s design for a guinguette, a tavern devoted to eating, drinking, and cabaret performances, is ornamented with tableware, bottles, and wheels of cheese and has columns shaped like wine barrels. The theme of earthly delights is developed in the plan at right for a hammock inside a lush garden that contains flowers producing the “odor of paradise.”

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Tavern and Hammock of Love, from

Civil Architecture, ca. 1810

Pen and black ink, gray and brown wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

And We Shall be Mothers Because…!

The meaning of this transgressive image of a nun baring her breasts is ambiguous. Lequeu’s cryptic caption may allude to the suppression of the religious orders in 1792, when such institutions were condemned as bastions of social oppression. Such anticlericalism contributed to dechristianizing practices under the Reign of Terror, including mass executions of clergy and coerced marriages. The gesture of stripping off age-old habits and devoting oneself to procreation corresponds with the revolutionary goal of reinventing society, a sentiment echoed in Denis Diderot’s novel Memoirs of a Nun (published posthumously in 1796).

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

And We Shall be Mothers Because . . . !, 1793–94

Pen and black ink, black and gray wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Engineering Fantasies

Ultimately, Lequeu’s skills as a draftsman helped him earn a living. He worked in the offices of the national land registry from 1793 until 1815 and at the École polytechnique from 1795 to 1796. His meticulous knowledge of geometry and perspective and his facility in producing exacting wash drawings proved useful in designing maps and representing machinery.

The designs Lequeu made in the first two decades of the nineteenth century are some of his most inventive. He turned his imagination to everything from gardens to temples, from theater interiors to subterranean chambers. Perhaps most striking are the designs in which a building’s form and decoration announce its function, a genre later known as architecture parlante, or speaking architecture. These varied and imaginative designs reveal that Lequeu continued to develop ambitious schemes throughout his bureaucratic career, long after he was forced to retire in 1815 and had abandoned any hope of seeing his creations realized. Anticipating his place in history, he even designed his own tomb.

Grove of Aurora, from Civil Architecture

Lequeu here envisaged a “satyr island” with a secluded fish pond surrounded by a topiary enclosure in a “moresque and arabesque” style. The statues at center depict the goddess Aurora restraining the young hunter Cephalus. While in Ovid’s Metamorphoses Cephalus resists the goddess’s embrace and remains faithful to his wife, Lequeu reinvented the tale, recounting that the “chaste Cephalus” was forced by his “corruptress” to “salute [Aurora] each day with harmonious sounds.”

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Grove of Aurora, from Civil Architecture

Pen and gray-brown ink and wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

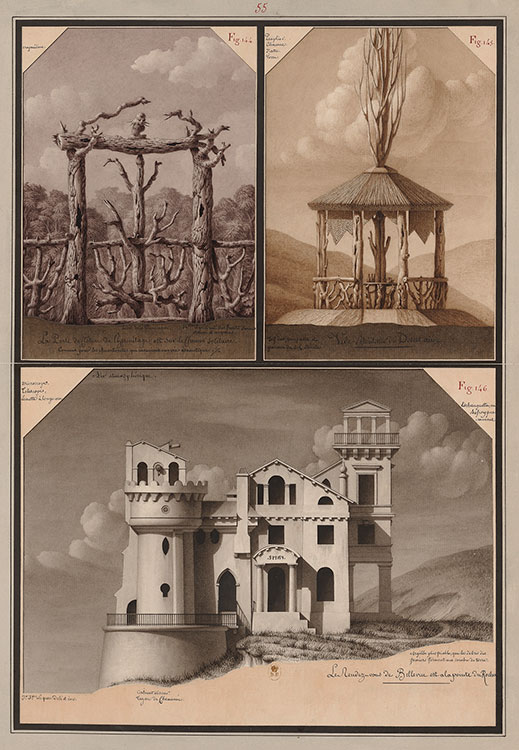

Hermitage Gate, a Desert Drinking Pavilion, and a Hunting Retreat, from Civil Architecture

These three studies explore the architecture of isolation. At upper left, a gate to an anchorite hermitage is composed of a tangle of dead branches, forming an effective barrier to the outside world; at upper right, a vide-bouteille—a pavilion for drinking and outdoor gatherings—is set in a remote location at high altitude. At bottom, a belvedere, or building designed for gazing at a beautiful view, sits at the edge of a cliff. Asymmetrical yet perfectly balanced, the belvedere combines elements of a classical temple, a medieval fortress, and a Renaissance villa. Once inside, a visitor could admire the view through a telescope or one of the curiously shaped windows.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Hermitage Gate, a Desert Drinking Pavilion, and a Hunting Retreat, from Civil Architecture

Pen and black ink, gray and brown wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

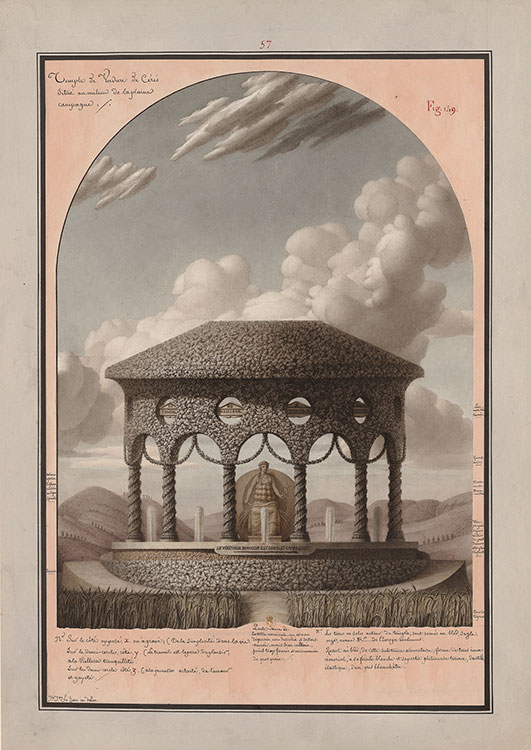

Temple of Ceres, from Civil Architecture

This design for a pastoral temple devoted to Ceres, the Roman goddess of agriculture and the harvest, idealizes rural life. The structure, a curious combination of stone and foliage, is approached through fields of wheat, emphasizing the carved motto “True happiness is found in the countryside.” Inscriptions on the plaques in the canopy of the temple follow the republican calendar. Below, Lequeu transcribed several quotations, including “Work is often the father of pleasure,” from Voltaire’s Upon Moderation in All Things, Study, Ambition, and Pleasure (1738).

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Temple of Ceres, from Civil Architecture, 1793–1805

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Machine for Circulating Water throughout the Castle, from Civil Architecture

Ever pragmatic, Lequeu included designs for a comprehensive sewage system and a mechanism to distribute water in his depiction of a Moorish pleasure palace. Inside the tower, the wind would lash a stretched canvas, moving a vertical chain that carries a bucket of water from the moat to a channel, which would distribute the water through the structure. At

right, Lequeu added a recently invented lightning rod to protect the building.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Machine for Circulating Water throughout the Castle, from Civil Architecture, ca. 1800–1805

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Designs for an Altar and Baptismal Font, from Civil Architecture

Even toward the end of his life, Lequeu continued

to pursue opportunities to show his drawings. In 1821, he submitted these two designs to a competition preceding the baptism of the duc de Bordeaux, grandson of the future King Charles X, planned for May at Notre-Dame de Paris. In the freestanding altar at left, the lamb is a symbol of life, while in the font the same animal symbolizes death through sacrifice.

Lequeu’s design also connects the water of eternal life and the bloodshed of the “artisan from Nazareth.” The altar’s tympanum is ornamented discreetly with the instruments of the Passion, while the apse above the font is crowned with stags’ heads, evoking Psalm 42: “As the deer pants for streams of water, so my soul pants for you, O God."

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Designs for an Altar and Baptismal Font, from Civil Architecture, ca. 1821

Pen and brown and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

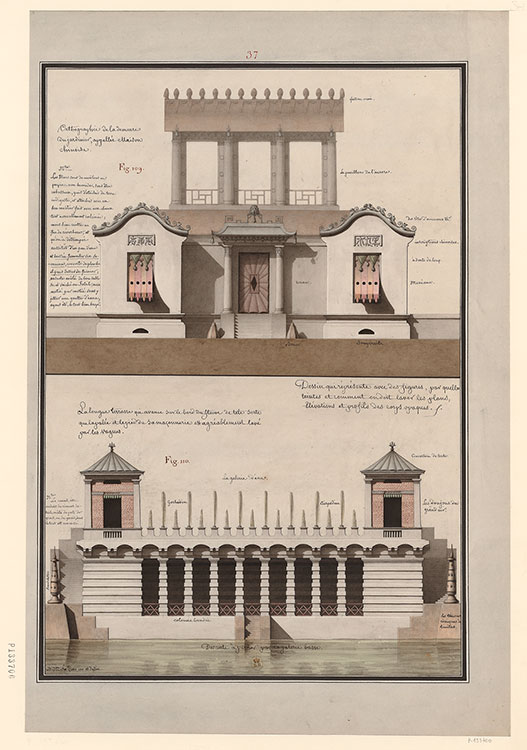

Chinese-style Gardener’s House and a Terrace on the Banks of a River, from Architecture civile

In the upper design, Lequeu began with the outline of a Cantonese house that he derived from the Scotsman Sir William Chambers’s 1757 treatise on Chinese architecture. He then enriched the facade with ornament of his own invention, including pseudo- Chinese inscriptions, bells, and animal-headed scrolls atop the cornices. The open-air pavilion on the second story is devoted to the rising sun and features a gabled roof decorated—somewhat unexpectedly—with turbaned heads. The lower design on the sheet features a two-story terrace along a riverbank that forms a spectacular gallery of waterspouts, which is flanked by two donjons crowned with tents.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Chinese-Style Gardener’s House and a Terrace on the Banks of a River, from Civil Architecture

Pen and brown and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

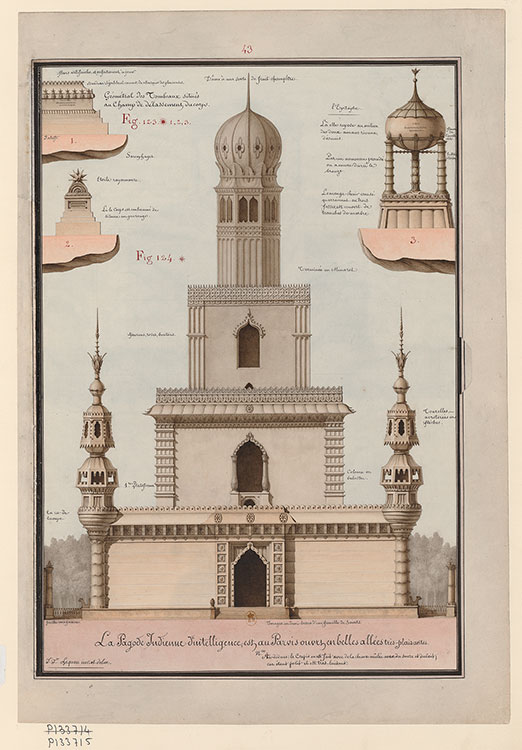

Indian Pagoda of Intelligence, from Civil Architecture

Lequeu combined disparate traditions in this design of a pagoda crowned with a minaret. The exterior was to be coated in a mixture of lime, sugar, and milk and then polished to create a glittering effect. While the design reflects Lequeu’s idea of Indian Mughal architecture and reveals his curiosity about other cultures, the language used to describe the building is indebted to classical theory.

At the top of the sheet, the artist included three tomb designs. The tomb at right bears a mysterious epitaph: “There she rests among two rival

lovers, separated.”

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Indian Pagoda of Intelligence, from

Civil Architecture, ca. 1815–20

Pen and black ink, brown wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Design for a Theater Interior, from Civil Architecture

Lequeu had an enduring enthusiasm for theater. He wrote at least nine plays (now lost) with such satirical titles as The Man with Two Wives, Nadir the Great, and The False Dmitry, Tsar of Russia. He also produced a number of designs for theaters and stage sets. This design for an auditorium shows five tiers of loges, box seats, and galleries. The restricted depth of the galleries to only three rows of seats, as indicated by the plan at bottom, produces a contrast with the soaring verticality of the entire structure.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Design for a Theater Interior, from

Civil Architecture

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Cow Barn and Gate to the Hunting Grounds, from Civil Architecture

Lequeu tested the limits of architectural symbolism in these two designs where form follows function. The barn below is in the shape of a cow draped in a gold- and silver-studded Indian blanket. Its monumentalism and exotic connotations evoke the colossal plaster-and- wood elephant erected in the Place de la Bastille in Paris in 1813. The upper design depicts an entrance to a princely hunting reserve decorated with the heads of wild boar, deer, and hounds. It was intended to be sculpted in “pork stone,” a mix of limestone and sulfur that, according to the artist, diffused “an odor of cat urine . . . [or] rotten egg.”

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Cow Barn and Gate to the Hunting Grounds, from Civil Architecture, ca. 1815

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Jennifer Tonkovich: The term architecture parlante or speaking architecture, was coined in 1852 by the romantic architect Louis Boullée, to describe the works of one of Lequeu's neoclassical contemporaries, Claude Nicolas Ledoux. Speaking architecture is architecture whose form announces its function as this cow-shaped building reveals its role as a barn for cows, or as a roadside vegetable stand in the shape of a tomato, tells you what it's there for. The term was meant to be pejorative and reflects a later perspective on designs produced in the late 18th and early 19th century. While this design for a barn is highly inventive, it's also part of a larger effort by Lequeu's contemporaries to envision eccentrically shaped structures in the form of animals. This isn't as bizarre as it seems. In 1811, Napoleon envisioned a bronze elephant surrounded by a fountain and surmounted by a viewing platform at the center of the newly created, Place de la Bastille. The project advanced as far as having a full-scale plaster model installed in 1813. The bronze was never produced, but the plaster elephant stood for decades deteriorating in the weather. Lequeu's design participates in this wider effort to test the limits of unconventional structures.

Dairy and Chicken Coop, from Civil Architecture

Lequeu’s design for a dairy barn is filled with bovine references: the columns sprout udders and are topped with cow’s heads, and a butter churn sits atop the spire. The exterior announces the building’s purpose in a direct and amusing way. More understated in comparison, the chicken coop is surmounted by a metal dome, meant to reflect sunlight, whose rounded curve resembles an egg—with the figure of a chicken at

its summit.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Dairy and Chicken Coop, from Civil Architecture

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Geometric Map

In 1802, Lequeu was reassigned to an office responsible for cartography in the department of the interior, where he would spend years shifting between positions as a geographical draftsman. Among his responsibilities were new maps of Paris, which were necessitated by Napoleon’s reorganization of the city. In this drawing, produced around the same time, Lequeu indulged in the opposite of documenting the urban fabric: he created a bird’s-eye view of an imaginary landscape with a sinuous river and undulating topography. The artist curiously “signed” the drawing with the playing card at lower left, which contains a pun on the sound of his name: The Heart, or Le Cœur.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Geometric Map, 1801

Pen and black ink, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

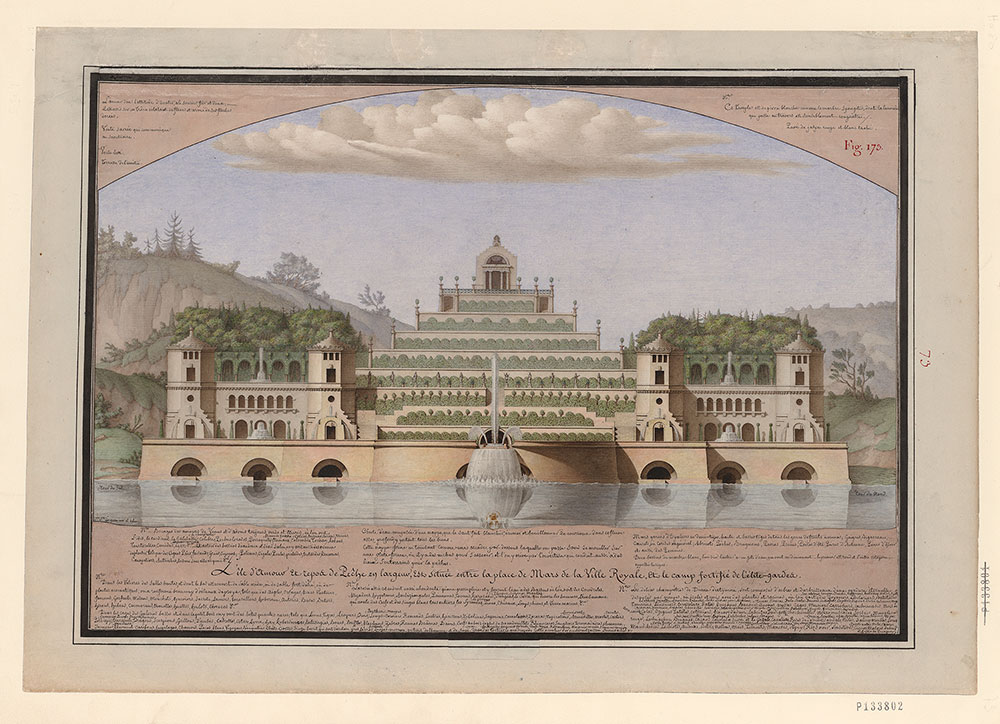

Island of Love and Fisherman’s Rest, from Civil Architecture

Situated between the military grounds of a royal city and a fortified encampment for elite troops, this island offers a quiet place for repose. Rising from the waters, a series of monumental terraces houses a menagerie of wild animals and birds in cages or in the surrounding woods. Lequeu painstakingly enumerated the many creatures in a series of lists. The island is surmounted by a temple of white stone paved in red jasper, which, as Lequeu notes, emits a rosy glow in daylight—an effect the artist had read about in an early eighteenth-century description of a castle in Ankara, Turkey.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Island of Love and Fisherman’s Rest, from Civil Architecture, 1810–25

Pen and black ink, brown wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Jennifer Tonkovich: While some of Lequeu's designs were practical or produced for competitions, others describe entire realms he invented. To better understand these imagined environments, we need to delve into the lengthy, handwritten paragraphs that offer even greater detail than the drawings themselves. The notes on this page reveal the incredible depth of Lequeu's book knowledge, his curiosity about the natural world, and his ability to create an environment enriched with unheard-of biodiversity. For example, among the animals found on the island's menagerie, he lists lions, tigers, leopards, bears, lynx, fox, otters, hedgehogs, tamarins, sable, tapirs, sloths, armadillos, beavers, and even unicorns. Many of the more obscure creatures on the list are animals described in travel literature. Thus, the list includes a creature from the Maldives described as a pimones, which is now thought to be a type of shark. Also on the list is a water hog from Zaire called an embiziangulo, which Lequeu found described in a 1714 publication on African Rivers. Lequeu's lists reveal the research that went into developing a vision for his fantasy island.

Temple of Divination, from Civil Architecture

An example of Lequeu’s fascination with ritual spaces, this sheet depicts a temple that would have served as the locus for the initiation of ancient Greek priests. A flaming river feeds into the temple, producing the billowing smoke at center, while Y-shaped divining rods, alluding to the mysteries known only to adepts, adorn the pillars flanking the entrance. To counter the sulfurous odor of the river, the sanctuary would emit an aromatic perfume—the recipe for which Lequeu includes—whose sweet vapor evoked dreams.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Temple of Divination, from Civil Architecture, ca. 1798–1802

Pen and black ink, gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Grotto of the Oceanids, from Civil Architecture

The present sheet invites the viewer into the “marvelous” dwelling of a group of mythological water nymphs. This three-story cavern, illuminated by an oculus, forms a microenvironment replete with water jets, singing birds, and plants growing on compost. A surrounding aqueduct supplies the water for the monumental cascade. Lequeu’s annotations note that the grotto, half-disguised as an artificial mound above ground, was to be situated at the end of a cloister and in front of a labyrinth, an elaborate and entirely imaginary setting.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Grotto of the Oceanids, from Civil Architecture

Pen and black ink, gray and brown wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

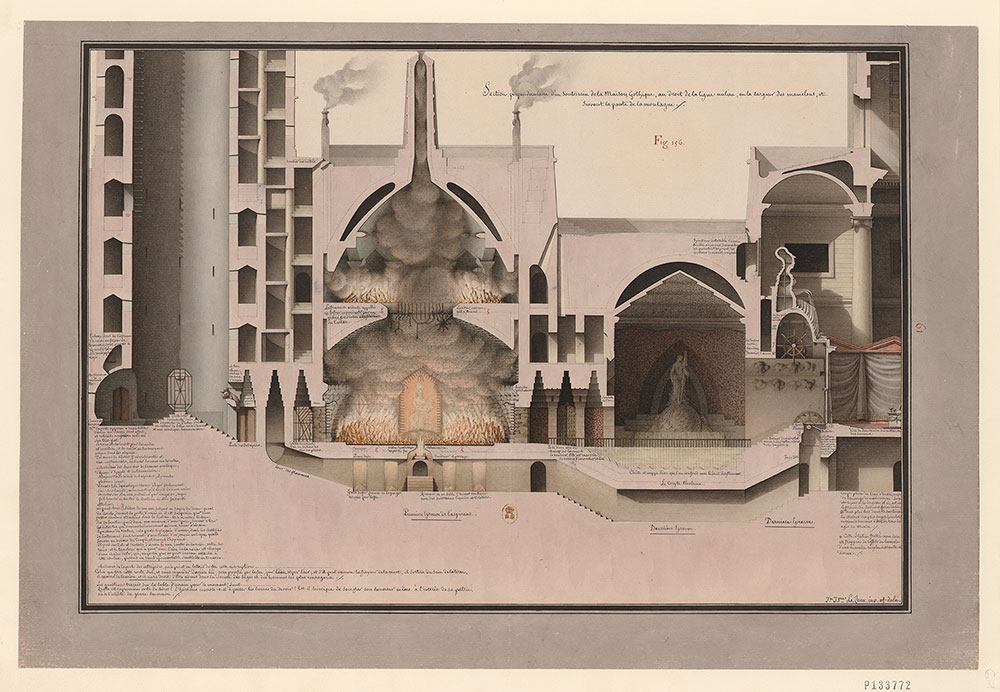

Underground of a Gothic House, from Civil Architecture

Freemasonry was a prominent cultural movement in the France of Lequeu’s day. While he seems to have been part of the brotherhood and knew the secretive Masonic initiation rites, it is not known to which lodge he belonged.

This structure, located behind a temple devoted to Minerva (seated at right), is designed for initiations into the “Society of Sages and Most Courageous Men.” According to Lequeu’s annotations, the ritual to join the brotherhood required initiates to overcome their fear of death through trials by fire, water, and air in subterranean chambers before emerging into the light. Each chamber would be equipped with complex mechanisms meant to produce claps of thunder.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Underground of a Gothic House, from Civil Architecture, 1804–11

Pen and brown and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Jennifer Tonkovich: The Masonic Brotherhood emerged in France in the 1720s and continued to grow in popularity as the century progressed. The Brotherhood admitted male members from all social classes as well as foreigners, and as a result, the Masons were seen with suspicion by the monarchy and the Catholic Church. Members were associated with lodges or meeting places for local chapters. The democratic nature of the lodges became associated with support for the revolution, and thus membership carried with it a whiff of danger. While we know Lequeu was intrigued by the Masons, recent research has not concluded that he belonged to a particular lodge. Lequeu's preoccupation with Masonic rites informed his work. Ancient Egyptian practices shaped some of the rituals in Masonic lodges and a general fascination with Egypt flourished, after the 1731 publication of the Abbé Terrasson's 6th Volume, Life of Sethos, which purported to be the translation of a lost ancient manuscript, but was actually a fantasy novel. This connection between contemporary ritual and the rites of the ancient world seems to have fascinated Lequeu, who had keenly felt a deep connection to the past. The clandestine rituals of the lodge fueled this design for an underground series of chambers filled with challenges for the initiate.

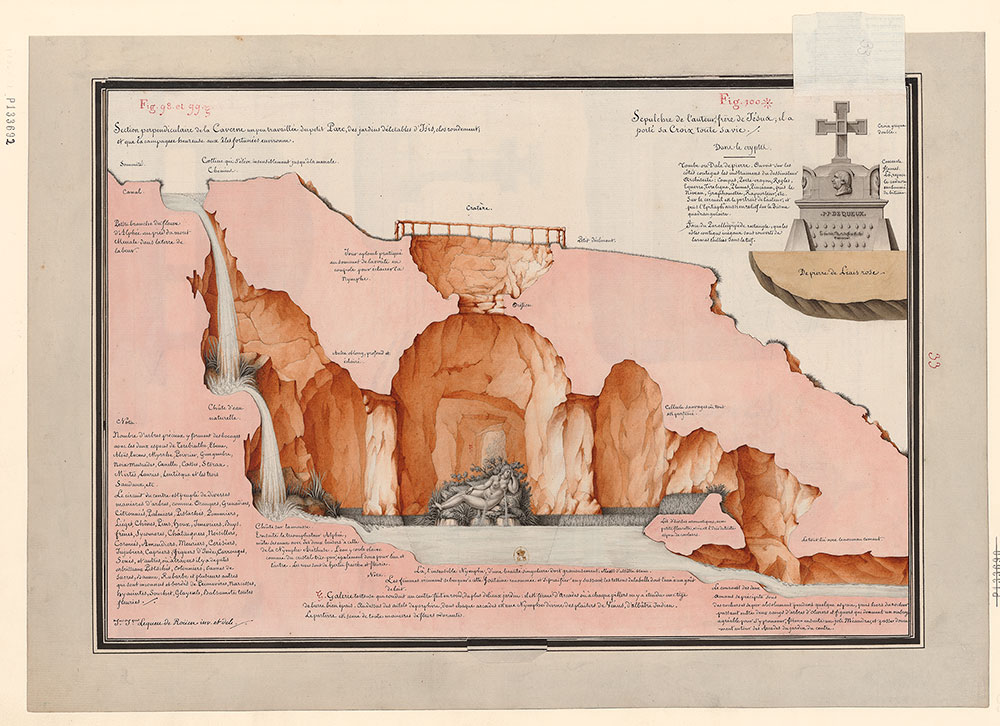

Cavern in the Gardens of Isis, from Civil Architecture

For this depiction of a grotto in the gardens of Isis, the Egyptian goddess of fertility, Lequeu turned to Ovid’s tale of the nymph Arethusa. She was transformed into a spring to elude being raped by the river god Alephus; the god, in turn, transformed himself into a river to follow her further. Here, Alephus is represented as the cascade at left, and the waters mingle in a cavern whose oculus Lequeu’s inscription refers to as an orifice. The figure of the nymph recalls a description in the erotic Renaissance novel The Dream of Poliphilo. Lequeu owned the 1804 edition of the text.

At upper right, Lequeu envisioned his own tomb, containing his “cadaver embalmed in bitumen.” The sepulchre is surmounted by the instruments of Lequeu’s profession as an architectural draftsman, including a compass, rulers, and porte-crayon. Beneath the flap of paper on which the tomb is drawn, however, is an alternative design bearing a Greek cross—an echo of Lequeu’s bitter remark that he carried the cross his entire life.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Cavern in the Gardens of Isis, from Civil Architecture, ca. 1810–25

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor, patch with revision at upper right

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Jennifer Tonkovich: The last decade of Lequeu's life leading up to the donation of his drawings to the Royal Library was rife with challenges. At the end of September 1815, the 58-year-old Lequeu was forced into retirement with a modest annual pension. He became increasingly isolated and his morale seems to have deteriorated. His writings reveal his feelings of bitterness and anger toward his peers. He described his outlook in a letter. As for the architect, Lequeu, having lost the property of his ancestors by revolutionary laws and by other misfortunes that result from it, he consoles himself with his wisdom, he cultivates the arts and sciences he loves. Bored with the deceitful world and its extravagances, he seeks in the solitary paths of the fields the secrets of nature, the course of the stars, but above all, he strives to adorn his soul by pure virtue, this gift of God. But he was not to have a tranquil time in his retirement. He struggled, as all urban dwellers do, with noisy neighbors, lamenting to his landlord, "If you have a good memory, you'll recall that my room is my design office where I work. That people at home must not hear a hurly-burly in the morning, including the Lord's days of rest. And even at night, two individuals noisily drop boots and bang shoes." It was in his apartment where he produced over 800 drawings and where he contended with obnoxious neighbors. That Lequeu died at the age of 69 on the 28th of March 1820.

Timeline

| 14 September 1757 | Jean-Jacques Lequeu is born in Rouen, the son of a master carpenter. |

| 1770–73 | He studies at the Rouen Public School of Design. In 1772, his studies after sculptures are awarded first prize in a drawing competition. |

| 1778 | He receives first prize in architecture from the Rouen Academy and designs a monument to the glory of Louis XVI. |

| 1779 | Lequeu moves to Paris. He becomes a draftsman for Jacques Germain Soufflot (1713–1780), the leading neoclassical architect in Paris. After Soufflot dies the following year, Lequeu continues his work with Soufflot’s nephew François Soufflot (1750–1801). |

| 1786 | Lequeu is made an associate member of the Rouen Academy. He works as a draftsman and inspector for François Soufflot and oversees the construction of the Hôtel de Montholon in Paris. |

| 1789 | The French Revolution begins. The First Republic lasts from 1792 to 1794, the Directory from 1795 to 1799, and the Consulate from 1799 to 1804. In 1804, Napoleon is crowned emperor. The empire lasts until 1814. |

| 1790–93 | Lequeu becomes head of a public studio in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine area, near Paris. In 1791, he designs an amphitheater for the Festival of the Federation, celebrating the anniversary of the storming of the Bastille. |

| 1792–1815 | The French Revolutionary Wars begin in 1792, continuing through the decade. After Napoleon’s ascension to power in 1799, the conflicts continue as the Napoleonic Wars. During this period, Lequeu is employed as a draftsman in the land registry offices. |

| 1794 | Lequeu submits five projects to the design competitions organized in year II of the republican calendar. On 23 October 1794, he is elected a member of the Popular and Republican Society of the Arts. |

| 1795–96 | Lequeu works as a draftsman at the École polytechnique. At the land registry offices, he is qualified as a “very skilled draftsman” by his superiors. |

| 1797 | He is made head draftsman for the Commission of Public Works, “responsible for producing the tracings and copies of maps requested by the government.” |

| 1802 | Lequeu submits a proposal for a monument celebrating the Treaty of Amiens that is exhibited in the Gallery of Apollo in the Louvre. He writes a manual on how to wash laundry. |

| 1808 | He exhibits the painting Exterior View of a Chapel of the Gothic Palace of the Grand Andeli at the Salon, the official exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris. It would be his only work accepted by the Salon until 1814. |

| 1814–30 | The monarchy is restored in France and continues, with the exception of Napoleon’s Hundred Days in 1815, until 1830. |

| 1815 | In September, Lequeu is forced into retirement with an annual pension of 668 francs. |

| 1817 | Lequeu decides to sell 93 drawings—architectural works, maps, and a self-portrait—but he cannot find a buyer. |

| 1822 | He publishes another advertisement for the sale of his drawings, to little response. |

| 1825 | He donates 823 drawings to the Royal Library, as well as collected press cuttings, letters, and autobiographical notes. |

| 28 March 1826 | Lequeu dies at one in the morning in his small two-room apartment at 33, rue Saint-Sauveur in Paris’s 2nd arrondissement. |