Hogarth: Cruelty and Humor

William Hogarth (1697–1764), one of the most acclaimed British artists, created iconic works that capture urban life in Georgian London. Fiercely independent, Hogarth was driven to innovate and developed new genres and modes of expression in his painting, printmaking, and drawing in an effort to elevate the status of British art. Hogarth: Cruelty and Humor features the Morgan’s exceptional cache of six sheets preparatory for two of Hogarth’s most revered print series, both issued in February 1751: Beer Street and Gin Lane, and the Stages of Cruelty. Bringing together the extant drawings related to these series, the exhibition explores Hogarth’s working method and examines his use of satire in agitating for social reform. The story of the creation, dissemination, and impact of Hogarth’s images reveals an artist who addressed the ills and injustices of life in a modern metropolis.

Hogarth: Cruelty and Humor is made possible with generous support from Joshua W. Sommer and Alyce Williams Toonk, and with assistance from the Alex Gordon Fund for Exhibitions and Raphael and Jane Bernstein.

William Hogarth (1697–1764)

Self-Portrait

ca. 1735

Yale Center for British Art

Paul Mellon Collection, B1981.25.360

Colin B. Bailey:

Hello. I'm Colin B. Bailey, Director of the Morgan Library & Museum, and I'm delighted to welcome you to Hogarth: Cruelty and Humor.

William Hogarth is one of Britain's most iconic artists known for his witty and innovative satires. This exhibition focuses on the Morgan's six proprietary drawings for two of his most revered print series, Beer Street, and Gin Lane, and The Four Stages of Cruelty. These rarely exhibited drawings shed light on Hogarth's creative process and on his role in agitating for social reform. These sheets were part of the extraordinary collection of old master drawings formed by the artist and dealer, Charles Fairfax Murray, and purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan in 1909.

The exhibition also includes loans of drawings from the Royal Collection and the Yale Center for British Art selected to complement the Morgan's work and to deepen our understanding of Hogarth as a draftsman.

As you move through the gallery, look for the audio symbols to discover commentary from curators in our Department of Drawings and Prints who provide further insights into the historical and artistic context of these fascinating drawings.

Thank you for joining us at the Morgan. We hope you enjoy your visit.

The South Sea Bubble

By 1720, Hogarth had set up his own shop as an engraver and enrolled in local drawing academies. He enjoyed his first success with prints satirizing contemporary political situations. In this drawing for one of his earliest engravings, the artist lampooned the perpetrators of a recent financial crisis. Thousands of European investors had become embroiled in a speculative scheme dubbed the South Sea Bubble and were financially devastated by its collapse. Hogarth’s interpretation of the consequences of speculation is particularly brutal. At center and left, the naked figures of Honor and Honesty are being beaten by Self-Interest and Villainy; a merry-goround twirls madly at center, laden with a prostitute, a nobleman, and a clergyman, reflecting the diversity of the scheme’s victims. This initial sketch reveals Hogarth developing his talent as a narrative artist steeped in the conventions of contemporary satire.

The South Sea Bubble

1721

Graphite; incised with stylus

Royal Collection Trust, Windsor Castle

Laurel Peterson:

This is Laurel Peterson, Moore curatorial fellow in the Department of Drawings and Prints here at the Morgan.

In 1720, the 22-year-old William Hogarth set his sights on a new career. After spending more than five years apprenticed to a modest silver engraver, he wanted to become an independent artist. He set up his own shop and entered the world of printmaking. Prints were widely available in 18th century London. They could be seen at booksellers, hung in print shop windows, and examined in one of the city's many coffee houses. Hogarth quickly began producing his own print designs, such as the preparatory drawing for a satire that we see here.

Graphic satires such as this one are forerunners to the political cartoons we know today. In the 18th century, they had become particularly popular as an increasingly literate and news-conscious group of people engaged with political events. In 1720, these prints proliferated when the financial bubble burst following widespread speculation in the South Sea Company, Hogarth's drawing of the South Sea Bubble juxtaposes allegorical figures with recognizable urban elements to critique the follies of that financial scheme. 18th century contemporaries populate the foreground.

Look at the priest wearing a wig just left of center. The large plinth towering over the scene is modeled on the well-known monument to the fire of London. The allegorical figures provide pointed commentary on the consequences of the scheme. They also suggest Hogarth's lofty ambitions as an artist for he draws on older imagery. For example, beneath the monument, the standing figure of honesty whose bare back is being beaten by two-faced villainy recalls imagery of the scourging of Christ.

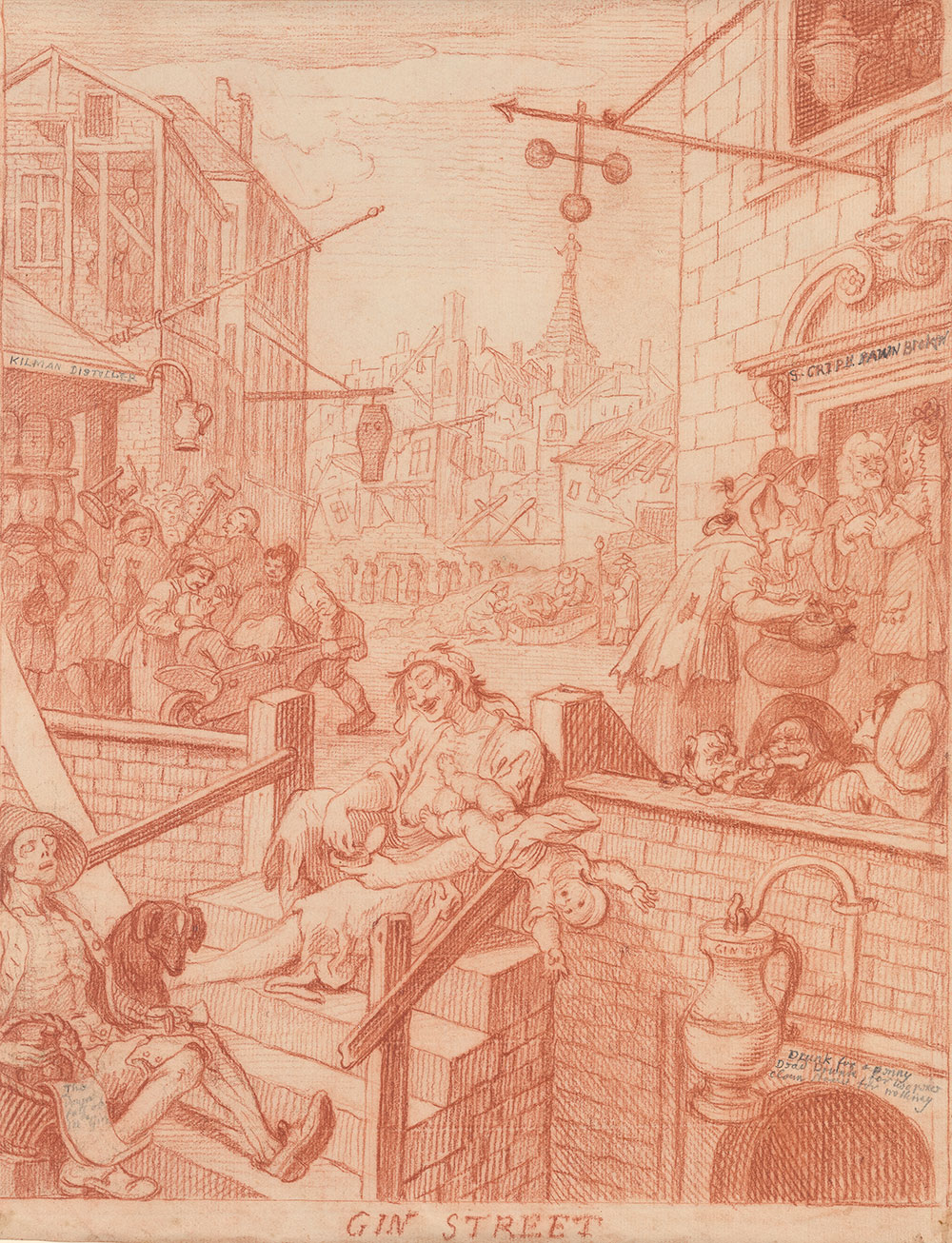

Gin Lane

The more alarming events in Gin Lane explore the degradation that went hand in hand with drinking imported gin, a scourge that was thought to target women in particular. At center, a drunken mother seated on stairs above a gin cellar drops her baby as she reaches for a pinch of snuff. Others caught up in the Gin Craze pawn their clothes and kettles to buy the drink, while their fellow Londoners fight dogs for bones or attack each other outside the aptly named Kilman Distillery. At upper left a suicide hangs from the rafters, while a burial takes place beneath a coffin maker’s shop sign. The recognizable setting—with the tower of St. George’s, Bloomsbury, in the distance—is the impoverished and derelict district of St. Giles in Westminster.

William Hogarth (1697–1764)

Gin Street

1750–51

Red chalk, over traces of black chalk (in left foreground), with graphite, incised with stylus; verso rubbed with red chalk for transfer.

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1909

The Morgan Library & Museum, III, 36.

Jennifer Tonkovich:

Hello. I'm Jennifer Tonkovich, the Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator of Drawings and Prints here at the Morgan.

The term gin craze refers to a period in the 18th century, from roughly about 1720 until 1760, during which gin had a major social impact in London. Dutch-made gin became widely available around 1700, and as London grew as a city, gin's popularity soared. In response to the moral panic brought about by such widespread consumption, and its effects, several gin acts were passed to govern the distillation and distribution of gin, beginning in 1729.

Not long after Hogarth published his prints, Beer Street and Gin Lane, his friend, the novelist and magistrate, Henry Fielding, published his inquiry into the causes of the late increase in robbers linking the rise in crime to the consumption of gin. Shortly thereafter, parliament passed the Gin Act of 1751, which did indeed reduce the amount of gin sales in London.

The public effects of gin drinking were dramatic and Hogarth seized on examples with contemporary relevance. For instance, the mother jettisoning her infant as she grabs a pinch of snuff, would've reminded viewers of the scandal of Judith Dufour, who, in 1734, strangled her two-year-old daughter, and sold the clothes she wore to buy gin. In Beer Street, the scene is much more jovial, although when Hogarth completed the print, which he had revised a few times, it had become much rowdier and bawdier, but still less dire than the scene on Gin Street.

The gin craze finally began to wane by the 1760s after legislation cracked down on the number of suppliers and a grain crisis led to a brief ban on distilling. Hogarth's images, however, have remained iconic representations of the anxiety generated by alcohol consumption.

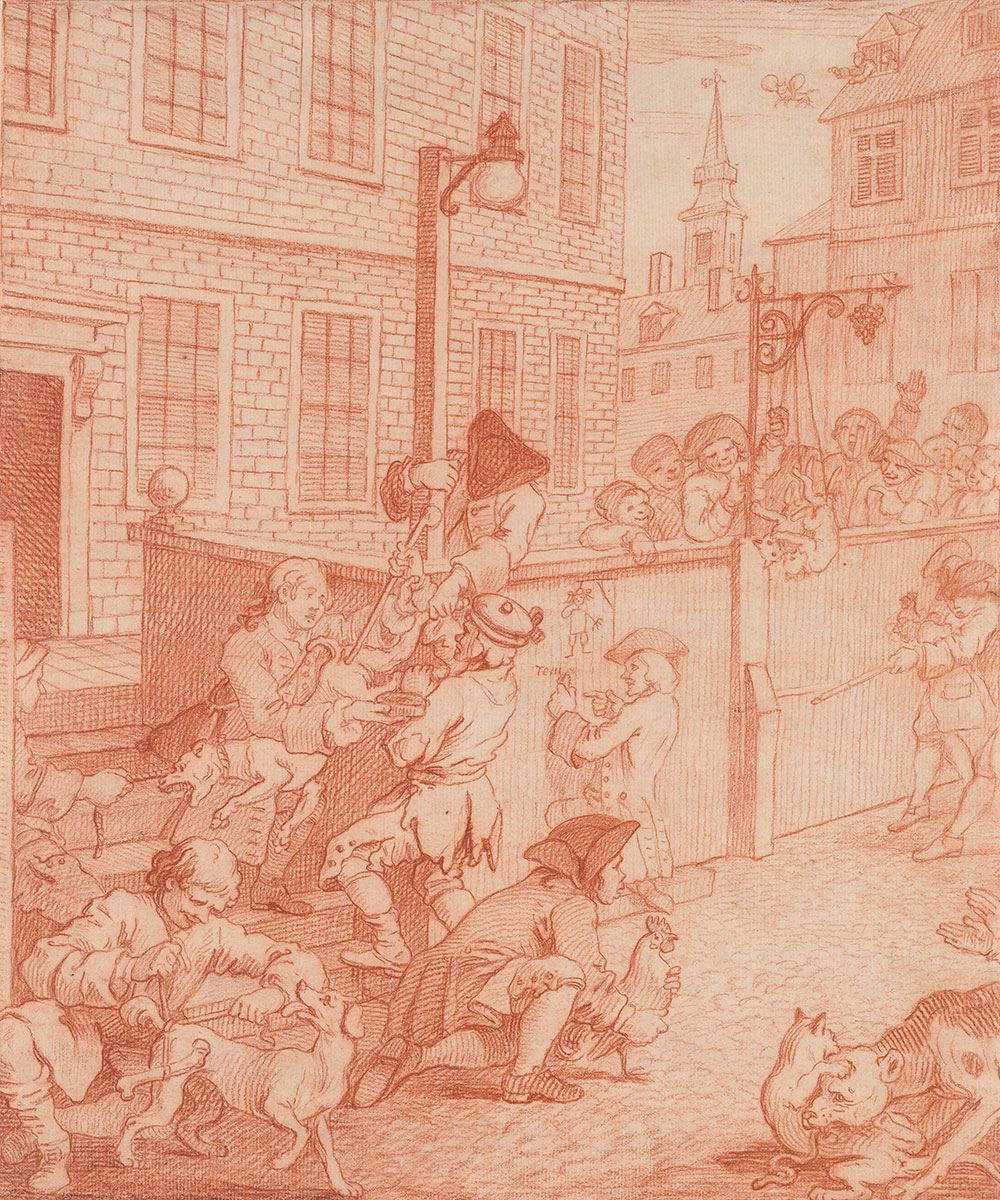

First Stage of Cruelty

Here we meet the youthful protagonist of the Stages of Cruelty series, Tom Nero. An orphan lacking parental guidance, Nero ignores the well-dressed boy offering him a tart and continues sodomizing a dog with the pointed end of a cudgel as his mates hold the hound in place. All around them, other children demonstrate this nascent stage of cruelty: tying a bone to a dog’s tail, staging a cock-throwing contest, and hanging two cats by the tail. The animals also turn on each other, and a dog disembowels a cat in the foreground. Eerily hinting at Nero’s fate, another child labels his hangman drawing Tom. Working on this drawing after the study shown to your left, Hogarth adjusted the scale of the figures relative to their setting and made other refinements to the composition in preparation for the print.

William Hogarth (1697–1764)

First Stage of Cruelty

1750–51

Red chalk; incised with stylus; verso rubbed with red chalk for transfer.

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1909.

The Morgan Library & Museum, III, 32b.

Jennifer Tonkovich:

As you look at the drawings and prints for the first two Stages of Cruelty, you'll notice various appalling acts of violence being committed against dogs, cats, horses, bulls, roosters, birds, donkeys, and sheep. In the third stage, the protagonist, Tom Nero, has moved on to a human victim. But what do these scenes of brutality to animals tell us about Hogarth and animal welfare in the 1750s in London? And was Hogarth's claim that he made this series in hopes of preventing that cruel treatment of poor animals, which makes the streets of London more disagreeable to the human mind than anything whatever, actually effective?

Hogarth had his own companion animals, most famously a pug from whom he was inseparable for a decade, and which earned him the derisive nickname Painter Pug. Others shared Hogarth's concern for animals as occasional resistance to public spectacles of animal cruelty arose in London, but sports such as bear and bull baiting, dog fighting, cock throwing, and the abuse of livestock were not addressed by legislation until the early 19th century.

This period saw the origins of a pro-animal welfare movement with greater representation of animals, primarily dogs, and their capacity as pets to first aristocratic and then middle-class families. And so Hogarth could reasonably assume to stoke sympathy for the sodomized dog in the first stage of cruelty and condemnation of the boy tyrant attacking her. The return of the dog in the fourth stage, now feasting on the boiled heart and innards of her tormentor, cleverly reminds us that animals have a story too.

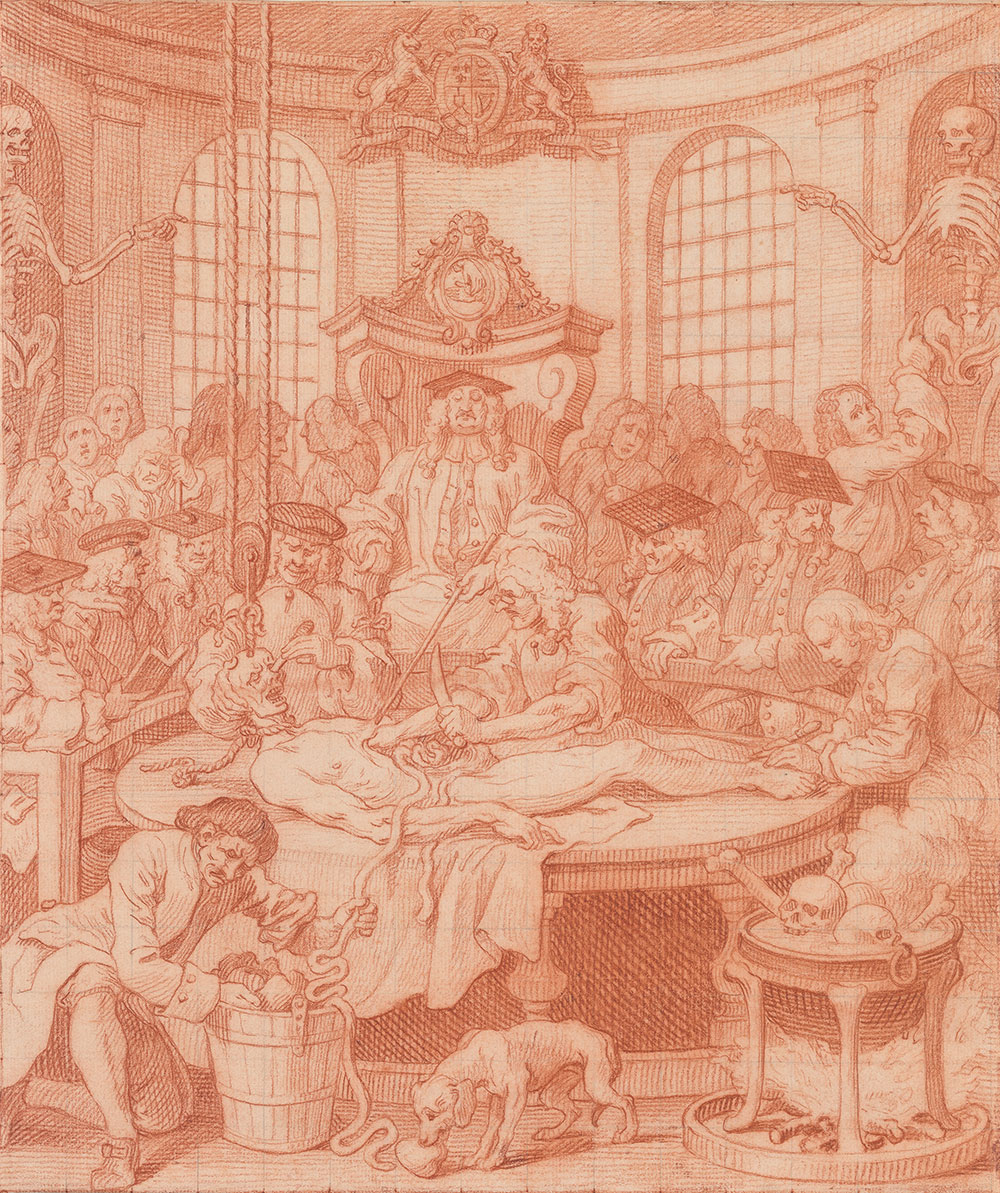

Fourth Stage of Cruelty

Fresh from the gallows, Nero’s corpse is brought to a medical theater, where it is disemboweled and dissected by three surgeons while a senior faculty member supervises. As one surgeon pierces Nero’s eye socket, another delves into his rib cage to pull out his intestines, which an attendant stuffs into a bucket. In the foreground, a dog licks Nero’s heart in an act of poetic justice. Bones boil in a cauldron at right, indicating that the ultimate fate of Nero’s body is to await reassembly into an anatomical model—a truly fitting end to his career as an abusive miscreant.

William Hogarth (1697–1764)

Fourth Stage of Cruelty (Reward of Cruelty)

1750–51

Red chalk; incised with stylus and squared for transfer in graphite; verso rubbed with red chalk for transfer.

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1909.

The Morgan Library & Museum, III, 32e.

Jennifer Tonkovich:

The Third Stage of Cruelty depicts Tom Nero being nabbed by a posse of townsman as he stands over the slain body of his pregnant lover. He has cut her deeply in several places, most dramatically across her neck. The inside pocket of his coat reveals a pistol, while the murder weapon, a bloody knife, has been found close at hand.

This and the next scene in which Nero's body is brought from the gallows to the surgical theater to be transformed into an anatomical model, speak directly to contemporary legislation governing the act of murder and the ultimate fate of the murder's body once executed.

The Murder Act of 1751 was intended as a deterrent at such violent crime by increasing the infamy associated with murder. It denied the convicted murder the right to a burial and mandated the body be available for dissection or anatomic purposes, or that the cadaver be hung in chains. This desecration of the body and the rule that executions were to be scheduled no more than two days after sentencing were seen as a means to prevent the escalation of fatal violence.

It was at the same time that Hogarth's friend, the writer and magistrate Henry Fielding, founded the first organized police force called the Bow Street Runners. This marked a concerted effort to control and investigate violent crime and make apprehending criminals a responsibility of the state rather than an onus on private individuals who had often been the victims of crime.

First Stage of Cruelty [print]

Hogarth’s prints for the Stages of Cruelty appeared on 21 February 1751, a week after Beer Street and Gin Lane were issued. These four prints were executed in the same coarse, linear style, and Hogarth’s moral purpose was hammered home through verses by the same author, the artist’s friend Reverend James Townley. Here Hogarth added a badge with the initials SG to Tom Nero’s jacket sleeve, indicating he is in the care of the parish of St. Giles-in-the-Fields, the location represented in Gin Lane. Hogarth added another instance of torture behind the balustrade at right: two boys hold a bird, and one blinds it using a heated wire.

First Stage of Cruelty

1751

Etching and engraving; first state of two

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

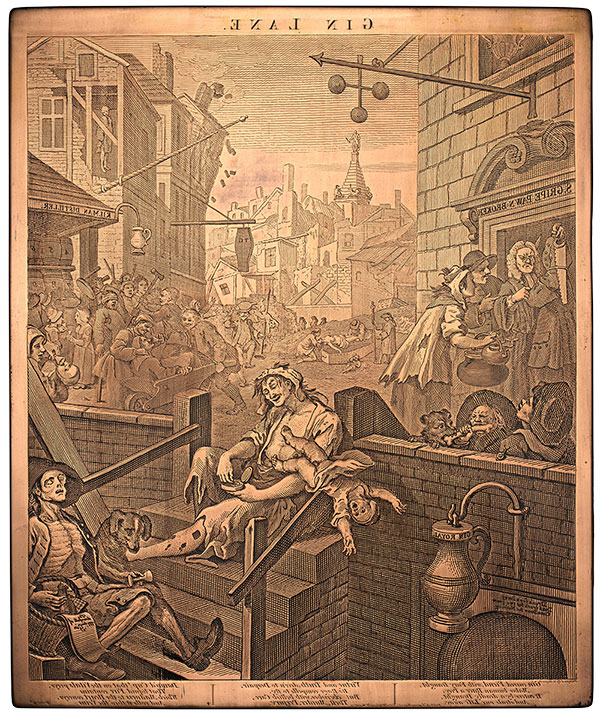

William Hogarth (1697–1764)

Gin Lane

1751

Copper plate (etched and engraved)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1921, 21.55.3

Jennifer Tonkovich:

William Hogarth first gained his fame by making print series after his own paintings, but later in his career as the artist tackled political issues close to his heart, he used drawings alone to design satires. Drawings could be completed more quickly than paintings, allowing him to respond rapidly to pressing issues as we see with The Four Stages of Cruelty. Engraving a copper plate such as the one of Gin Lane in the case behind you was a multi-step process. From the outset, Hogarth had to conceive of the composition in reverse for, when he printed the copper plate, the scene would be flipped. It's not entirely clear how Hogarth transferred each drawing's design to the plate. He may have coated the copper with white wax and then covered the back of the drawing with red chalk. When he traced the drawing on the plate, lines of red chalk would be left on the white surface.

While the drawings on display in this exhibition show evidence of tracing the differences between the Morgan sheets and the final prints suggest there was likely yet another set of drawings used for transfer, which are probably lost. After the transfer, Hogarth used a needle to scratch the design into wax. The plate would then be submerged in an acid bath and the acid would bite into areas unprotected by wax, leaving incised lines to hold ink for printing. Rarely satisfied with these initial results. Hogarth further developed the design by engraving directly onto the plate with a burin strengthening shadows and refining the composition. Once he was happy with the plate, he was able to print hundreds of impressions. Hogarth was a savvy businessman and when he sold a set of prints in 1751, he advertised two versions. The more expensive version was printed on a finer paper intended for connoisseurs.