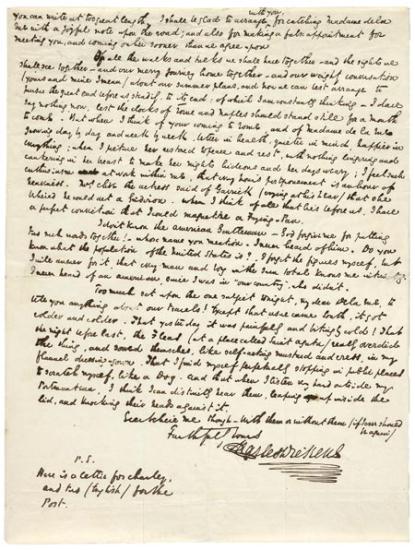

Autograph letter signed, Naples, 10 February 1845, to Emile de la Rue

Purchased in 1968

Dickens's letters to Emile de la Rue included progress reports on the positive effects of his mesmeric treatment of Madame de la Rue, which was no less fervent for being, by this stage, conducted in absentia. Utterly confident in his powers, Dickens told de la Rue that, "when I think of all that lies before us, I have a perfect conviction that I could magnetize [hypnotize] a Frying-Pan." The biographer Fred Kaplan argued: "Mesmerism provided Dickens not only with a rationale for the working of personality and mind . . . but with a language and an imagery that could be dramatically utilized in fictional creation." But Peter Ackroyd has suggested that for Dickens mesmerism was "part of his need to control, to dominate, to manipulate."

Mesmerism

In his life and art, Dickens worked energetically for healing. His fiction exposed many of the social ills of his day, and a significant portion of his later journalism is devoted to an impassioned campaign to improve sanitation and public health. Although he was a committed evolutionist and progressive in his attitude toward science and the improvements wrought by technological advances, he was also, by imagination and temperament, attracted to the fantastic and pseudoscientific. This was manifested in his interest in spontaneous combustion and phrenology as well as his fervent belief and active experiments in mesmerism (or "animal magnetism"), an early type of hypnotism.

Dickens was introduced to mesmerism through Dr. John Elliotson, his family physician and one of his "most intimate and valued friends." He became convinced of the therapeutic effects of mesmerism after witnessing Elliotson's demonstrations in 1838, and, although there is no record of Dickens undergoing the procedure, he learned to mesmerize others. Throughout the 1840s, he conducted mesmeric experiments on his wife and friends.

you can write at too great length. I shall be glad to arrange with you, for catching Madame de la Rue with a joyful note, upon the road; and also for making a false appointment for meeting you, and coming on her sooner than we agree upon.

Of all the walks and talks we shall have together—and the sights we shall see together—and our merry journey home together—and our weighty conversation (yours and mine I mean) about our summer plans, and how we can best arrange to pursue the great end before us, steadily, to its end: of which I am constantly thinking—I dare say nothing, now, lest the clocks of Rome and Naples should stand still for a Month to come. But when I think of your coming to Rome, and of Madame de la Rue growing day by day and week by week, better in health, quieter in mind, happier in everything; when I picture her restored to peace and rest, with nothing lingering and cankering in her breast to make her nights hideous and her days weary; I feel such enthusiasm at work within me, that every hour's postponement is an hour of heaviness. Mrs. Clive the actress said of Garrick (crying at his Lear) that she believed he could act a Gridiron. When I think of all that lies before us, I have a perfect conviction that I could magnetize a Frying-Pan.

I don't know the American Gentleman—God forgive me for putting two such words together!—whose name you mention. I never heard of him. Do you know what the population of the United States is?—I forget the figures myself, but I will answer for it, that every man and boy in the sum total knows me intimately. I never heard of an American, since I was in "our country", who didn't.

Too much set upon the one subject tonight, my dear De la Rue, to tell you anything about our travels! Except that as we came South, it got colder and colder. That yesterday it was painfully and bitingly cold! That the night before last, the Fleas (at a place called Saint Agata) really overdid the thing, and sowed themselves, like self-acting mustard and cress, in my flannel dressing-gown. That I find myself perpetually stopping in public places to scratch myself, like a Dog. And that when I listen very hard outside my Portmanteau, I think I can distinctly hear them, leaping up inside the lid, and knocking their heads against it.

Ever believe me though—With them or without them (if I ever should be again)

Faithfully Yours

CHARLES DICKENS